Brilliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

8.3 Work on George and Dorothea’s Future

8.4 The Rise of Dumcrieff and Middlebie

8.7 Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer to the Exchequer

8.8 The Jacobite Rebellion of 1745

8.9 Commissioner for the Forfeited Estates

8.10 The Forth and Clyde Canal

8.14 Other Activities and Interests

8 The First Clerk Maxwells

The origins of the first Clerk Maxwells, George and Dorothea, have already been briefly mentioned. George Clerk was the third son of the Baron, Sir John Clerk, and his second wife Janet Inglis (§6.6) while Dorothea Clerk (§5.3) was the only child of the Baron’s younger brother William Clerk and his wife Agnes Maxwell, heiress of Middlebie (§§6.2‒6.3). George and Dorothea were therefore first cousins. How they came to be Clerk Maxwells will now be revealed in this first detailed account of George’s life and career. On Dorothea’s part, the fact that she brought the estate of Middlebie into the Clerk family was to be a major influence in shaping the lives of the second Clerk Maxwell, her grandson John, and in turn his son James, who was the third and last of the line.

8.1 George’s Early Life

In Scotland, until fairly recent times, children were usually named after family members from earlier generations. This was certainly the case amongst the Clerks of Penicuik, but the naming of the Baron and Janet Inglis’ second surviving son was a departure from this protocol:

… it pleased God to make up the loss of my son Hary by the birth of another son, whom I christned George, after the patron of the cause which I had espoused during the Rebellion. He was born 31 octobr 1715. (BJC, p. 96)

The significance of the date and name was later clarified by Lord Eldin: [1]

… the day on which the [Jacobite] Rebels under Brigadier McIntosh advanced to Jock’s Lodge with an intention to surprize the City. He was named George after the King as testimony of loyalty’.

The eagerness of the Baron to call his son after the King was no doubt presaged by him already having called his second son James, as was customary, in honour of his wife’s father; the name of the Old Pretender was not at all popular with the House of Hanover, especially in 1715. We hear nothing more of George (or James either) for some time, but he seems to have been sent to Dalkeith grammar school[2] as were his younger brothers after him. He was boarded at the school and seldom brought back to Penicuik because it had unsettled him.[3]

While George was away at school his mother would write to him, for example, to remind him that he should pray, read the scriptures and keep the Sabbath.[4] In the following year, however, he was sent away to Lowther School[5] near Penrith in Cumberland, just before his fifteenth birthday (BJC, p. 138). The Baron had heard about the good reputation of the school and the progressive outlook of its master, Mr Wilkinson; the bad memories of his own school days (see §4.1) no doubt helped persuade him, but it was ever in the Baron’s mind that his sons should learn ‘the English language’. However, he did not go so far as sending him to Eton, as he had done with his first son, John, for while it had been a great success he had concluded: ‘… there was this bad consequence from an English Education, that Scotsmen bred in that way wou’d always have a stronger inclination for England than for their own Country’ (BJC, p. 99). Penrith was in England, but only just, and it would have been hard to find any school in England that was closer to home. George was therefore packed off to Lowther with this encouragement from his father:

You have nothing else to depend on but your being a scholar and behaving well. (BJC, p. 139n1)

The same theme was expanded on in a letter to George the following February. The Baron hoped that his son was beginning to love learning, was acquiring English language, and following the good example of his teacher. He reminded him that he should be good towards his schoolmates since they could well be of help to him later on in life, and that if he were to be seen as being a mere trifler and a bad scholar, he would never be able to live it down.[6] After visiting Dumcrieff that August, the Baron proceeded to Penrith to pay his son a visit at Lowther. He stayed three days and ‘found all going very well with him’ and likewise he found that Mr Wilkinson fully lived up to his expectations (BJC, p. 139). While George received plenty of letters, he seems to have been a reluctant correspondent; his mother longed to hear from him and told him so in May 1732 when she wrote telling him of his new baby brother, Matthew, and of Mr Wilkinson’s good opinion of him.[7]

A year later, however, both his mother and his sister Betty were still chiding George for not writing. Betty in particular, who was some ten years his elder, complained that she never heard from him, and when she sees him next she fears they will be strangers. Apart from once more reminding him of his failure to write, his mother asked him what sort of career he had in mind.[8] Interestingly, his cousin Dorothea, then aged twelve, also wrote to him.[9]

The year 1734 finds George nearly nineteen and still at Lowther.In the August of that year, the usual time for his annual peregrinations, the Baron had George brought up to join the family at Dumcrieff, and thereafter they all set off for Carlisle so that his wife Janet and daughter Anne could see a little of England. Having stayed only a few days, they returned to Drumcrieff (BJC, p. 143), but the Baron omits to say whether George came back to Penicuik with them then or went on back to Lowther. It would seem that the approach of his nineteenth birthday would have been an appropriate time for him to proceed to university. Lord Eldin (Clerk, 1788, p. 51) informs us that he duly went to the University of Edinburgh, but there is no mention of him graduating there (Laing, 1858). Even James Clerk Maxwell, George’s great-grandson, did not do so; they both went on to complete their education elsewhere. For George, it was a case of following in the footsteps of his father, his uncle William and his brother James, who all went to Leiden.

8.2 An Early Marriage

The decision to send George to Leiden, or at least the timing of it, was affected by a singular event, for on 17 July 1735, while George was still only nineteen, he married his cousin Dorothea,[10] who was then just a month short of her fifteenth birthday (§5.3). Since her father William’s death in 1723 the Baron had been one of Dorothea’s tutors, and following her mother’s death some five years later, she had been brought into his care and presumably would have lived with him and his family at Penicuik. She and George had therefore ample opportunity to become acquainted. In spite of her young age, the marriage was legal, for the legal age of marriage for girls was then just twelve (Lorimer, 1862), and amongst the upper classes marriages between such young couples had often taken place as a way of binding the families together with the real business of married life beginning sometime later when the young couple were judged mature. Nevertheless the marriage was irregular. According to the Baron, the marriage took place ‘privately’ (BJC, pp. 144−145), which probably means that they went before a minister without proclamation of banns or any other of the usual formalities. There were indeed ministers who might do this sort of thing,[11] and perhaps for a suitable consideration. We know for a fact that the wedding was irregular because some years later George paid a ‘fine’ to the kirk session of St Mungo’s in Penicuik: ‘1740 Jany 20 Given in [i.e. a fine] by George Clerk for his Irregular marriage with Dorothea Clerk’.[12] Presumably in return his marriage to Dorothea then became regular.

The Baron later said of the liaison:

I had no hand or concern in the Match, but I hope it will prove a happy Marriage to both. I never recommended her to George, since I was her Tutor, but she had this advantage, that her Mother, before she died, frequently recommended George to her. (BJC, pp. 144−145)

She was just seven years old at the time of her mother’s death, and George was then only twelve. One wonders if his remarks here were simply to gloss over how the marriage would have looked to others. Is the Baron therefore trying to distance himself from the notion that it may have been his own wish, for the young heiress would have made an excellent ‘prospect’ indeed for one of his own sons? In his Life of James Clerk Maxwell, Lewis Campbell clearly felt obliged to indicate a hint of incredulity at the idea of it being Agnes’ idea.[13] Agnes could indeed have said such words to her daughter in the playful sort of way that one does with children, but hardly more. If she seriously had any such match in mind, it would have been something that she would have put to the Baron himself, for without his approval it would be no more than a fond wish.

As Dorothea’s tutor and latterly curator, the Baron had had many years to ponder over Dorothea’s future, for although she had a decent legacy from her stepfather Major Le Blanc, her inheritance through the entail of Middlebie was heavily burdened with a string of debts (§6.2) a messy problem that the Baron would have to untangle. First, we can be fairly sure that the Baron did his best to see that Dorothea was brought up in his own Protestant religion. Not only would that have been natural for him to have done so, it also meant that there would be no problem with the troublesome 1701 Act. Furthermore, her marriage, just short of her fifteenth birthday, to one of his own sons would be likely to dampen any mention that her mother had been Roman Catholic. This would help to avoid her having to take the oath prescribed under the Act, which she would have been required to do, by the age of fifteen at the latest, if she were not by then accepted as being manifestly Protestant. Failure in this matter would have resulted in Dorothea being debarred from her inheritance. But she could not marry his eldest surviving son, James, for he would inherit Penicuik, the requirements of which were mutually incompatible with those of the Middlebie entail. Moreover, he also needed to provide a decent future for his next son, George. It would have to be George and Dorothea.

That settled, his next task would be to unburden the Middlebie estate from debt, to which end it was necessary to find a means of getting out of the entail. Furthermore, the times being what they were, he would have had to worry about what would happen if Dorothea died without issue. It would be a pity if Middlebie ended up being lost to the Clerk family and went instead to the Areskines who, as the heirs of Grizzel Grierson, were the next in line to succeed (see §6.3 and §6.4 and note 31 of Chapter 4).

8.3 Work on George and Dorothea’s Future

After the marriage, the Baron got to work arranging things for the young couple. First of all, he got Dorothea to make a will in George’s favour,[14] which was followed up sometime later by a disposition and assignation to him of all the non-entailed lands, goods and monies that might belong to her on her decease.[15] We may guess that the intent of this was to secure matters for his son as far as was possible under the constraints of the entail.

The accumulated debts on Middlebie were a different matter, some of them dating as far back as 1720, they came to a total of £1,759 1s 6½d.[16] Against this, the property entailed by John Maxwell in 1722 comprised the following:[17]

- In the County of Dumfries

- The Twenty Merk Land of Middlebie

- The Merk Land of Kirktoun of Kilmahoe

- In the Burgh of Dumfries

- The south-most tenement of a land near the Friars Vennel, with yard

- A tenement in Bells Wynd, near the port of the Friars Vennel, with large yard

- A yard in Friars Yard

- A house at the head of the White Sands, with yard

- Five acres of land at the back of the Castle Gardens

- A yard adjacent to the above land, with barn at the foot of the Upper Green Sands

- A quarter’s salmon fishing on the Nith, west and south of the town, from Powson’s to the Powfall Burn

- In the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright

- Nether Corsock

- Over and Nether Blackhills

- Little Mochrum

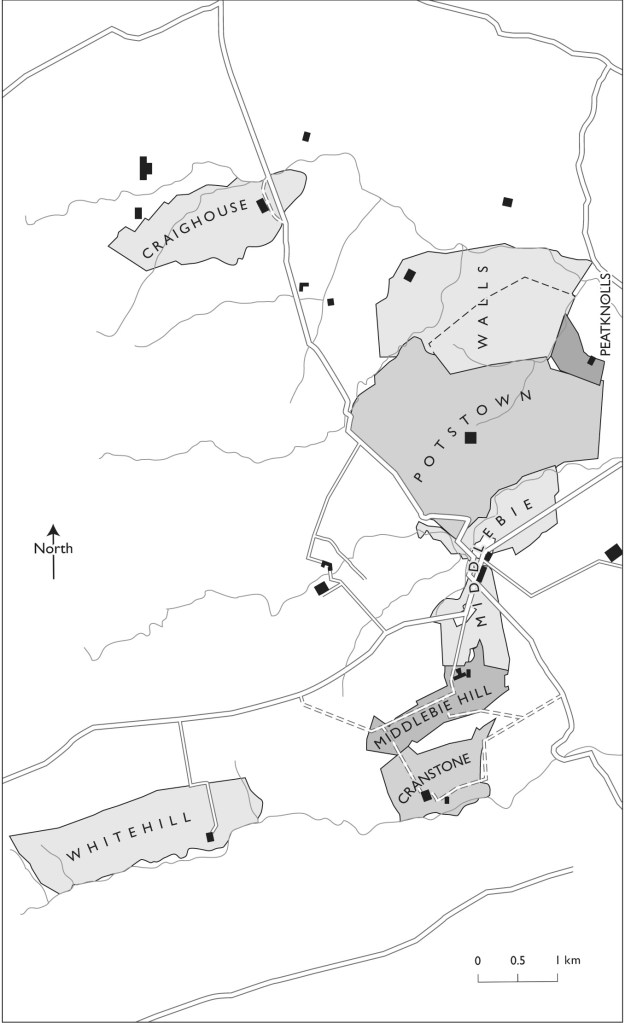

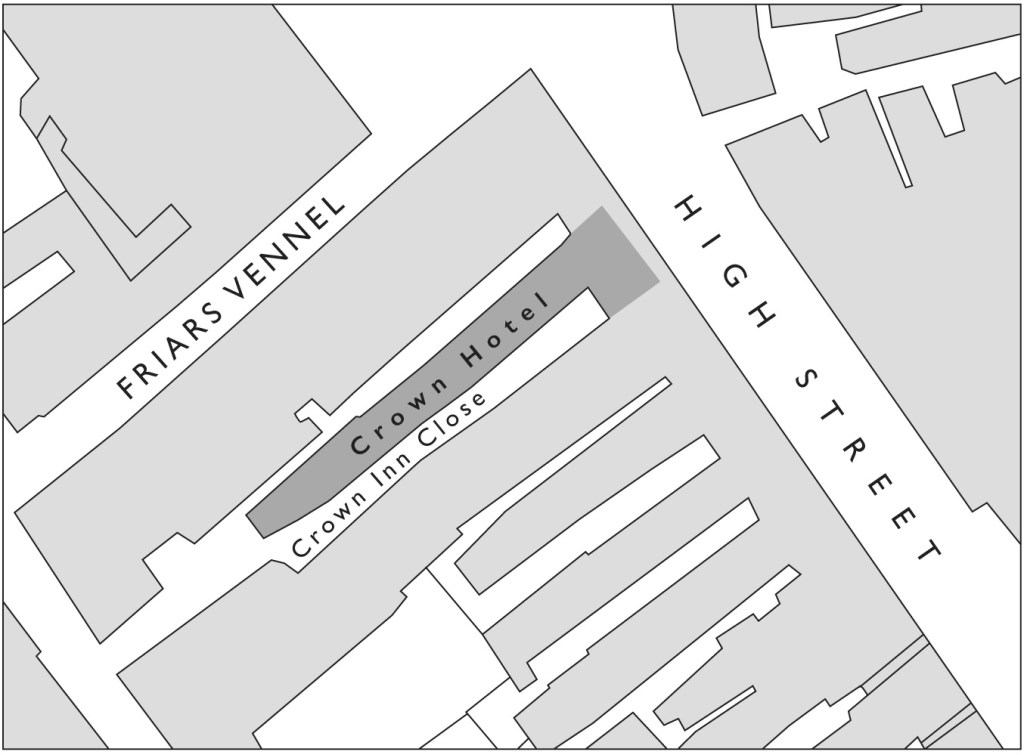

The locations of the major parts of the estate and Middlebie itself can be found from Figures 2.1 and 8.1, while the original plan for Middlebie town is reproduced in Plate 8.1. Figure 8.2 shows the location of one of the main properties in Dumfries, indicated in the list by an asterisk, which in James Clerk Maxwell’s time was the Crown Inn. Who would have thought that James Clerk Maxwell owned a ‘pub’?

The Twenty Merk Land of Middlebie would sell for £2,225 4s 4⅔d, calculated as twenty-three times the annual rental. The debt of £1,759 1 6½d could then be paid off leaving a surplus that could be put to the purchase of some other small property nearer to the remainder of the estate in and around Dumfries. But in order to do this, a private Bill had to be introduced into the House of Lords to obtain the requisite Act of Parliament allowing the entail to be broken: the Baron certainly had the legal skills and the necessary connections to ensure that it would succeed.

There are eight such pen and ink sketches depicting the individual parcels of land that made up the Middlebie estate as shown in Figure 8.1. The Middlebie Town property, shown here, is very irregular in shape and almost split in two by being squeezed in by Church land on the north and the Duke of Queensberry’s property on the south. In addition, the Marquis of Annandale owned an enclosed area within the western part the property, while the Duke of Queensberry had a similar piece out of the eastern part. The ‘town’ itself is just a few buildings. We must assume that this, either on its own or together with some of the contiguous pieces of land, was the originally entailed Twenty Merk Land of Middlebie. The Merkland of Kirtoun of Kilmahoe, however, was entirely separate and lay a few miles north of Dumfries (See Figure 2.1).

From DGA: GGD56/19, 18th C, by courtesy of Dumfries and Galloway Libraries Information and Archives.

In the meantime, however, following the marriage of George and Dorothea the Baron sent George to Leiden to continue his studies, while Dorothea remained in the care of the Baron and his wife at Penicuik, his reasons being:

As my s[ai]d son seemed very intent to study the Law in Leyden, and his Wife and he being too young to live together, I sent him to Holand in January 1736, where he had the advantage of staying with his eldest Brother James. (BJC, pp. 144−145 )

Despite them ‘being too young to live together’ it seems as though the marriage was consummated, for a child was born in the following year.

Constructed by the author from the eight individual sketches in DGA: GGD56/19, Plans of Middlebie Estate.of which Plate 8.1 is one example.

While George actually departed in January 1736, the intention of sending him away was already raised by the previous October, for his uncle Hugh had found him a travelling companion.[18] But from George’s standpoint, it was probably just a bit too soon, for not only did he have a marriage ball to give, he would also be reluctant to be parted so quickly from Dorothea. Moreover, by then they may also have been aware that their first child was on its way, which we will examine in more detail later on in this chapter.

George eventually set off for Leiden in the New Year and while he was ever the reluctant writer when at Lowther, he may have found some consolation in exchanging letters with Dorothea. However, only his general correspondence seems to have been preserved; for example, letters concerning his classes at Leiden, an intended tour of Germany with his brother James, the sighting of a comet, and failed attempts to get his father a Great Dane.[19]

In the meantime, Dorothea spent some time back at Dumfries, having visited an uncle, Robert Maxwell, there in the autumn of 1736.[20] Just who he was is not absolutely clear. Agnes Maxwell had a younger brother Robert who, if he was still alive in 1722, was not mentioned in the Middlebie entail, but her father, ‘the Entailer’ did have a half-brother, Robert Maxwell of Shalloch,[21] who died in the winter of 1737 and was therefore alive when the letter was written.[22]

On finishing his studies at Leiden in the summer of 1737, George accompanied his elder brother James to Germany, where he visited Hamburg, before returning home.[23] James, on the other hand, lingered on and extended his stay, just as his father had done before him (see §4.3).

This was one of the properties in Dumfries which came to Dorothea Clerk Maxwell through the Middlebie entail of 1722. A consequence of this was that it was inherited by her great-grandson, James Clerk Maxwell, in 1856.

8.4 The Rise of Dumcrieff and Middlebie

When George returned from Leiden in 1737, he had reached his majority and was, as we know, already a married man. While the Baron had at first diverted him from setting up house with his young bride, he was now in for a rather pleasant surprise. The Baron, having finished building a new estate and country house at Dumcrieff only four years before, now presented it to George for his very own country seat. He had spent five and a half long years building it, and no doubt a considerable amount of money, but he had its use for only five summers. Nevertheless, he would have been thinking all the while about his future provision for George and Dorothea, and the fact that he had given it away to George was of no great consequence in the grand scheme of things, and perhaps as it would turn out even a convenience. Since Penicuik would come to his eldest son James by right, he was already provided for, and he could also have the use of Mavisbank nearby when it came his turn to manage his father’s coal works at Loanhead (see §4.8).

Moffat lies in Annandale just over twenty miles from Dumfries, from where Middlebie and Nether Corsock lie about twelve miles to the east and fifteen miles to the west respectively. It would therefore be fairly convenient for access to Dorothea’s properties in these three places. Furthermore, when the Baron wanted somewhere to stay at Moffat for the summer season, he and his family could stay as guests of George and Dorothea, and could travel there without having to bring their entire retinue along with them from Penicuik. And so, in a way, he gained as much as he lost by his generous gift! The entire process was complete when George obtained the Crown Charter for his new estate in 1738, and was officially able to style himself ‘George Clerk of Dumcrieff’.[24] But by a different route, by the demands of the Middlebie entail, he was also George Clerk Maxwell.

Once installed as the new Laird and Lady of Dumcrieff, George and Dorothea did not simply settle down and live the lives of country gentlefolk, for George had to start a career. First of all, the Baron’s plans for sorting out their financial position had to be put into effect, beginning with George and Dorothea signing off on the Baron’s management of their affairs to date.[25] Dorothea no longer required the Baron to act as her curator since she was now the wife of George, who had reached his majority the year after they married. Just coming up to the tenth anniversary of Agnes Maxwell’s death, the Baron had Dorothea served as heir of entail to John Maxwell of Middlebie[26] This was followed by the private Bill which he was able to have introduced into the House of Lords 8 March 1738 (House of Lords, 1738, p. 222ff.). These key steps all took place within the space of a month. This must have been quite a feat, but the Baron clearly had both the necessary acumen and standing to achieve it.

The tenor of the Bill was that all the other heirs of entail had now been exhausted apart from two, first in line being Dorothea Clerk (and any future children) and, second, her distant relation James Areskine [Erskine], then a minor, the younger son of Charles Areskine, his Majesty’s Advocate for Scotland (see note 31 to Chapter 4). The Bill presented the Baron’s scheme of selling off the ‘Twenty Merk Land’ of Middlebie, the proceeds to be used to pay off the debts and to allow Dorothea to purchase in their place ‘other Lands or Tenements, fituated as near as conveniently to the faid George Clerk’s other freehold Eftate of Drumcreif’ (House of Lords, 1738, p. 222ff.). Apart from the substitution of these new lands for the Twenty Merk Land, the original entail was to stand exactly as it was, and to make sure it was all done according to the Act, trustees were appointed to oversee the ensuing transactions. They seem to have been an eclectic bunch, but most likely they were well-chosen friends and associates of the Baron, with some input from Charles Areskine.

The Bill’s progress through both Houses of Parliament was fairly rapid by today’s standards and was given the Royal Assent on 20 May 1738 (House of Commons, 1738). The plan to clear the debts on Middlebie was then put into action. In addition, since George and Dorothea’s financial state of affairs had now been made reasonably clear and secure for the foreseeable future, the terms for a marriage contract could be agreed;[27] and it is here, apparently, that the name Clerk Maxwell emerged for the first time. The lands of Middlebie were duly sold, only to be bought back by the Baron himself and made over to George. Why, if he had the money to do this, had he simply not handed over to George and Dorothea just half of that amount, which would have cleared off the debt without the bother and expense of the legal fees and Act of Parliament?

The Baron was, as usual, simply being astute. No doubt he would have mentally written off the issue of the debt many years before. Dorothea had brought a good deal into the Clerk family by way of land and legacies, but unfortunately it was she, not George, who had title to the entailed property. While it was she who owned the estate, in practical terms he could treat it as though it were his own ‘by right of his wife’. The sting in the tail was that if he needed to do anything formal, he would require Dorothea’s agreement and signature. But as a married woman, the protocol to be observed was that she would include the words, ‘on the advice and consent of her husband, George Clerk Maxwell’. Of course, his signature would have been accompanied by suitable matching words. It may have been irksome for George, and probably just so for Dorothea too, but to some extent it created a balance of power between husband and wife – neither could act without the agreement of the other. From the point of view of an eighteenth-century gentleman, however, he would be in much better standing if the property were his alone.

One of the intentional effects of an entail is that the property in question cannot be signed over to a second party, George for example, nor could this be done in the Act of Parliament, because that would have been more than strictly necessary for the purpose of clearing the debt. By disentailing and then repurchasing the Middlebie lands, the debt was paid and the property could become George’s. Possibly George and his father felt that it would prove a constant source of embarrassment if the Clerk Maxwells of Middlebie did not own the land whose name they bore. Although he did not obtain his official charter over Middlebie until much later,[28] he could now justifiably call himself either George Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie or George Clerk of Dumcrieff. In fact, he seems to have used whichever of them he felt best suited the occasion, and this is reflected both in his correspondence and elsewhere. Whatever may have been the Baron’s motivation, first with Dumcrieff and now Middlebie, George had done very well out of him.

Dorothea’s succession was not technically complete until sasines for her properties had been recorded in her favour. The sasines on Nether Corsock, the two Blackhills and Little Mochrum were registered in September 1738;[29] others are recorded in the Index to the Register of Sasines for Dumfries etc … 1733−1780 (SRO: 1931) from which it appears that, in due course, George also held property there.

8.5 Career and Family Life

Thanks to the Baron’s good planning, his acumen and generosity, by the end of the year 1738 George and Dorothea were comfortably set up to make their own way in life. They were well-off indeed, for not only did they have a splendid country seat with parkland, plantations and a farm at Dumcrieff, they also had the entailed Middlebie estate as a further source of income. George had done little to achieve such good fortune other than through circumstance and simply being his father’s son. This is reflected in the words of Lewis Campbell, in his commentary on the notes on the Clerk family written for him by James Clerk Maxwell’s cousin, Miss Isabella Clerk;[30] they amply capture the general tenor of George Clerk Maxwell’s progress through life:

This George Clerk Maxwell probably suffered a little from the world being made too easy for him in early life … In some respects he resembled John Clerk Maxwell, but certainly not in the quality of phlegmatic caution’ (C&G, p. 18)

However, it is not that he was some sort of wastrel incapable of lifting a finger to do anything on his own behalf. Far from it, he was an imaginative and industrious man, ready to turn a hand to anything that interested him; but therein lay the problem:

His imagination seems to have been dangerously fired by the “little knowledge” of contemporary science which he may have picked up when at Leyden … (C&G, p. 18)

As to what others may have thought about George, Campbell says:

in all relations of life, he seems to have won golden opinions … The friendship of Allan Ramsay [senior] and the affectionate confidence of the ‘good Duke and Duchess of Queensberry’, sufficiently indicate the charm which there must have been about this man. (C&G, p. 19)

Although George had been keen to study law at Leiden, he had soon come to the realisation that he was not cut out for it. Clerk (1788) gives us a good idea of where his aptitudes really lay:

… a skilful engineer and draughtsman, as appears from various roads, bridges, and other public works [31] … executed under his direction, or on plans which he delineated. Nor were his talents in designing confined to this more mechanical species of drawing.

It therefore seems that he was naturally of a technical bent and so it is unsurprising that the minutiae of legal work would have left him uninspired. He wanted something rather more ‘hands on’,[32] and he began with some farming. This is evident in a letter he received while at Dumcrieff from his brother Patrick, who was then at Penicuik, enclosing an improved recipe (a pint of honey to a pint of tar) for making an effective paste with which to smear his sheep, presumably to kill off ticks and parasites in much the same way as dipping does today.[33] Such things he dutifully preserved in his personal notebook, wherein there is another recipe for a sheep salve that he recorded almost exactly thirty-six years to the day thereafter.[34] It seems it was something he took quite seriously, for he wrote about it to the Trustees for Manufactures and they ordered the publication of two of his letters ‘Observations on the Method of Growing Wool in Scotland’ and ‘Proposals for Improving the Quality of Our Wool’ (Clerk Maxwell, 1756).

By the following year of 1739, however, George had set his sights on a fresh line of interest when he embarked on a more philanthropic yet seemingly practical venture that aimed to encourage and improve local manufacture by the setting up of a spinning school in Dumfries.[35] His petition to the Trustees for Manufactures in Scotland met with success.[36] At the same time, he also set up a linen factory there. While the spinning school’s purpose was mainly to teach girls to spin local wool, their skills would also have been employable in spinning flax to make linen yarn for the factory, of which, unfortunately, no details have been discovered. George and Dorothea based themselves in Dumfries for this purpose, and while we do not know for certain where they lived, we can at least be certain that they did live there by August 1739 because the Baron recorded it, ‘Drumfrise, where my son George and his wife had taken up their residence’ (BJC, p. 154), and in addition about this same time George also received letters addressed to him as George Clerk ‘at Dumfries’ and ‘at his house in Dumfries’.[37] It will be noted that his surname was then still largely known as being Clerk rather than Clerk Maxwell, an issue that we will return to in due course.

In August 1740, in continuation of their longstanding custom of vacationing at Moffat, the Baron and his wife stayed at Dumcrieff, with George and Dorothea, for a month. They visited the local spas and the menfolk, at least, enjoyed the shooting and fishing. He made a note of his stay there that gives us some idea of what the house was like inside.[38] It had been finished nine years before, and for the last three years it had been in George’s possession. Given its relative newness, it should have been in good condition, and there had been ample time to get it suitably furnished. The biggest room in the house, which was on the upper floor and about seventeen feet square was ‘ill provided with furniture’ and could have done with some sort of sofa bed. The ceiling was corniced, but the walls were bare and needed to be decorated with some printed linen wall hangings. As to the similarly sized dining room on the ground floor below, it was ‘not in order’; it needed to be decorated with painted wallpaper and some decent framed prints. Money may have been tight for George at this time, for during his stay his father paid for all of his family’s living expenses, including the mutton they had eaten and the grazing for his horses. Ever the kind and thoughtful father, the Baron also gave George one of his horses, and intended giving him the feu on a property in Moffat that would bring him a reasonable amount of money.

If the interior of the house was not to the Baron’s entire satisfaction, evidently the house as a whole was not to George’s, for two years later he had it extended and remodelled to such an extent that the central part had to be pulled down.[39] It would be reasonable to assume that he was now financially better off and able to afford such an undertaking. According to Window Tax records, sometime between 1748 and 1772 the house may have been enlarged once again, for the number of windows increased from twenty-one to thirty-five (Prevost, 1968, p. 204). However, since many householders took measures to avoid paying the tax, such as blocking off all but essential windows, the increase could equally well have been as a result of unblocking some that already existed. As to the progressive laying down of plantations, which had been one his father’s great passions, George was not quite as diligent. He did, however, lay down one fairly large plantation in 1774 at Aikrig, which borders the old Moffat to Carlisle road. It covered nearly twenty-five acres, but only the central part lying mostly to the north of the road, survives today (Prevost, 1968, p. 204).

As already mentioned, at this time George’s main residence was in Dumfries where he had his linen factory, but in 1748 there was an abrupt change for he was forced to close the factory down. Prevost (1968, p. 205) gives no details, but all the signs seem to point to it having taken place in that year for it was then that he took up a post with the Forfeited Estates, in consequence of which he and Dorothea moved to Edinburgh.[40] The post-1745 Board of Commissioners had not yet been set up and the Forfeited Estates had been placed under the control of the Barons of the Exchequer, of whom, needless to say, his father was one. At the same time he borrowed, together with his father, £320 from Archibald Tod, a businessman from West Lothian, who had been one of the trustees under the 1738 ‘Act for Dorothea’.[41]

8.6 Children

While the available evidence relating to the births of George and Dorothea’s children is somewhat fragmentary, a fair reconstruction is given in Appendix A17.4. They were, in chronological order:

- John, born in 1736 (with an outside chance it was late 1735!)

- Janet, baptised 7 July 1738, at Penicuik

- Agnes, born September 1739

- Joan, baptised 16 March 1741 at Dumfries, died November the same year

- George, born November 1742

- William, born 14 June 1744, died about May 1746 following inoculation against smallpox

- James, baptised 20 September 1745 at Dumfries

- Dorothea, baptised 27 February 1747 at Dumfries

- William, Robert and Johanna, all probably born at Edinburgh

- Janet, known as Jenny, married William Anderson WS, Clerk to the Signet, in 1775. Widowed in 1785, she was still alive in 1791.

Agnes married John Craigie, a Glasgow merchant who was the second son of the Lord President of the Court of Session, Robert Craigie of Glendoick.[42] Their daughter, Barbara Craigie, married Colonel Lewis Hay, and in turn their daughter, Agnes Clerk Hay, forged a link with the Irving family by marrying John Irving, half-brother of Janet Irving, James Clerk Maxwell’s paternal grandmother (see §§12.3‒4). A son, Captain George Craigie of the 40th Regiment of Foot, was killed in the final years of the American Civil War at the battle of Groton Heights, New London, Connecticut, in September 1781, of which more later, (Ladies Magazine, 1781, p. 613; Clerk, 1788).

John served in the Royal Navy but retired sometime after 1777, when he married Mary Dacre (also known as Mary Dacre Appleby and later Rosemary Dacre Appleby) of Kirklinton in Cumbria (1745−1834). She was the granddaughter of Baronet Fleming of Westmorland, the Bishop of Carlisle. John succeeded as 5th Baronet on his father’s death and died on 24 February 1798 (Foster, 1884).[43] As he had no children, his young nephew George Clerk, the eldest son of James Clerk HEICS and Janet Irving (see §9.2) was retoured as his heir. An account of what little is known of this John Clerk and his wife Mary Dacre is given in §9.1.

There is little information on George other than that he was admitted as an advocate on 21 December 1767, lived at the same address as his parents in James’ Court in Edinburgh’s Old Town Edinburgh and died unmarried on 5 October 1776. [44]

The third son was James, who also became a seaman but in the merchant fleet rather than the Royal Navy; he eventually joined the HEICS[45] as a lieutenant and possibly reached the rank of captain. He then settled in Edinburgh, where he married Janet Irving in 1786 (see §9.2). They were to be in due course the paternal grandparents of James Clerk Maxwell. James Clerk never lived to inherit the Middlebie estate from his mother, Lady Dorothea, who, by dying on 28 December 1793, outlived him by just two weeks (Mackay, 1989).

Dorothea married David Craigie of Dunbarney WS (d. 1796) who was the brother of John Craigie of Glendoick, her sister Agnes’ husband, in 1779 (Grant, 1922). They had a son who was named after his grandfather as George Clerk Craigie;[46] he became an advocate, married and had children.

William, the fourth surviving son, was so named in memory of his dead brother, which was not an uncommon practice at the time. Robert was the sixth born and last son. Both he and William went into the army and became lieutenants in the 1st and 56th regiments of foot, respectively. Sadly, both died in service. Robert died towards the end of 1781 at Gibraltar, where the British garrison had been held under siege by the French and Spanish since the winter of 1779. If he was killed in action, then this would possibly have happened during the sortie that took place on 27 November, when a party of the besieged British troops left the safety of their garrison by night in an attempt to forestall an imminent all-out assault by the enemy. The sortie was successful in delaying the assault for many months.[47] William died just a few months later during the siege of Brimstone Hill, at Basseterre on St Kitts, which began on 19 January and ended with surrender to the French on 13 February (Clerk, 1788, pp. 55−56; Foster, 1884).

Johanna, the second daughter mentioned by Foster (1884, p. 52)), was doubtless a later daughter named in memory of the earlier Joan who died in 1742. According to Lord Eldin (Clerk, 1788), ‘about 1782’ an unmarried daughter of Sir George Clerk, 4th Baronet, died of grief over the loss of her nephew and brothers in the war. As Janet, Agnes and Dorothea had all married, the unmarried daughter John Clerk was referring to must indeed be Johanna. The records do show that a Miss Johanna Clark died in November 1781 from ‘decay’,[48] which in the language of the time meant that she had simply wasted away. William did not die until after Johanna, who in fact died almost exactly at the same time as Robert. Such a tragic coincidence must have left a great impression on the minds of her friends and family.

8.7 Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer to the Exchequer

In 1743, George Clerk was appointed Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer to the Exchequer in Scotland. This obscure administrative office was quite different from the present day combined office now called the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer which, despite the incomprehensible title, deals with such things as ownerless goods, treasure trove, heirless estates and the like. It seems that the function of the original Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer was to audit the accounts of the sheriffs − presumably their personal accounts for sitting in court and perhaps extending to the expenses of the trials that they conducted. At any rate, in return for a broad range of benefits and expenses the incumbent was not expected to know too much about it, nor was he expected to attend his office ‘but infrequently’. That was how the system worked.

Such positions were obviously highly sought after, and for a man of appropriate standing and connections, the only reason for not seeking such an office would be seeking one that was even better. In July 1742, George was but yet only twenty-six years old and still accustomed to his father doing things for him; for example, by the age of twenty-three he had been given one estate and had the debts and legal entanglements of another resolved. Now his father was starting to pull some more strings to help him find a regular source of income. According to Scott (1981, pp. 162−163), William Allanson, the incumbent Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer, had not attended the court for over twenty years. The Baron had therefore approached him in the hope of persuading him to make way for George. It was not quite as straightforward as that, however, because Allanson’s nephew, Wyvill Boteler, was already acting as his deputy during the interim. The Baron’s angle was that Allanson’s nephew and George could share this post worth £200 a year. Allanson was not to be moved, but the Baron continued to press the matter and, to sweeten the request, he eventually offered Allanson a pension of £100 a year for life to step aside.[49] The offer was at first refused but when it was eventually accepted in the year following, 1743, George and Wyvill Boteler were appointed jointly to the office of Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer (Shaw, 1903). In a letter to the Duke of Queensberry some twenty years later, George revealed that he was only getting £86 10s out of it;[50] possibly the final negotiation ended up somewhat different from the anticipated 50/50 split, or George was having to pay back his father.

8.8 The Jacobite Rebellion of 1745

According to Lord Eldin (Clerk, 1788), it had been one of George’s fancies to see action as a soldier, and so when came the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 he joined the Royal Hunters, a private brigade of gentlemen volunteers who, equipped and provided for at their own expense, had come out in support of the government army led by the Duke of Cumberland (Prevost, 1963). Also known as the Yorkshire Hunters, they were commanded first by Major-General Oglethorpe, and from 1746 by General Hawley (Ferguson, 1889). Having joined General Wade at Newcastle, they were deployed in gathering information on the progress of the rebel forces. They followed Wade on his journey south to join forces with Cumberland[51] and thence followed the retreating rebels northwards in December 1745 as they headed back from Preston to Carlisle. While Lewis Campbell says that the Hunters assisted in retaking Carlisle (C&G, p. 192), Lord Eldin is more cautious, saying only that George was:

… on different occasions, employed by the Duke of Cumberland, (who knew him well) and, in particular, to conduct the forces to the proper ground for opening the siege of Carlisle.

This rings true, because George had first-hand knowledge of the area around Penrith from his schooldays. In a footnote, Ferguson gives some fragments of the pursuit:

a column under General Bland … [including] some Yorkshire Hunters … was endeavouring to get in front of the Highland artillery by a lane through the Lowther enclosures. The Duke with the main body was three miles behind.

We can imagine George being to the fore and, remembering the lane, suggesting it as a way to gain ground on the rebels. Notwithstanding George’s efforts on behalf of king and country, we find a slightly less daring impression of the Hunters from one of the Baron’s letters to his son during the campaign; it was sent from Durham where he was taking refuge with his wife and eldest daughter:

Tuesday 29th October 1745

General [Oglethorpe] was very friendly and told me that you was amongst the Hussars and that he wou’d take particular care of you. He regretted that his regiment was not more numerouse but said that you all wou’d be safe, tho’ you should never come within gun shot of the ennemy, and said he never designed to expose any of you. He told me you had marched to Morpeth to intercept deserters … I expect James every day. (Prevost, 1963, pp. 237−238)

The Baron’s concerns for his son’s safety are understandable given that another son, Patrick, had died at the battle of Cartagena in 1741. Also on his mind was Patrick’s twin brother Henry, who was then somewhere in the East Indies, and by now his concerns for him were growing by the day. It is clear that regiments such as General Oglethorpe’s allowed cautious young gentlemen to uphold family honour by serving their king and country without unduly exposing themselves to any real danger, and so the Baron had been much happier that George was serving his king in this way rather than enlisting in the army itself. Nevertheless, it was by no means ‘a picnic’. Not only was the late December weather very severe, the Hunters got close enough to the rear-guard of the rebels to get involved in a couple of dangerous situations. One such had taken place when they were marching on Lancaster. Having been surprised by some Highlanders who were hanging back at the rear of the rebel army, one of the Hunters was killed and another taken prisoner.

On 18 December, the Hunters were involved in a skirmish at Clifton, a village about halfway between Lowther and Penrith, an area George would have known intimately. Indeed so, for he sent his father a detailed sketch of the area, showing the dispositions of Cumberland’s troops and the rebel forces, and the locations where the engagements took place.[52] During the retaking of Carlisle at the end of December, the Hunters were stationed two miles to the north at Kingsmoor, but there is no mention of them having taken any further part in the campaign. They were dismissed from service on 30 December, upon which George, having acquitted himself well, returned to his wife and children at Dumfries. Dorothea had been forced to billet rebels, but they had caused little trouble and were now long gone and heading for Glasgow. From then on it was simply a matter of Cumberland’s army pursuing the rebels further and further north until a final battle became inevitable.

It is intriguing that so much is known about George’s exploits with the Hunters. In part we owe it to the surviving correspondence between him and his father, as reported by Prevost (1963). George, ever sparing with his replies, was now writing regularly, but the really surprising thing is that the correspondence kept flowing even in the thick of a military pursuit. Despite the times and conditions, the weekly post seems to have been able to find the Hunters wherever they went!

The final battle of the rebellion took place to the south-east of Inverness at Culloden Moor in the April of 1746. The Jacobites were done for, and although Bonnie Prince Charlie escaped, many of his loyal supporters, both high born and low, either perished on the field of battle or were ruthlessly hunted down by Cumberland and his men. Little mercy was shown, and so many were captured and condemned to die that it was decided that a bloodbath on so large a scale was unconscionable; lots were drawn for those who were to hang, with the remainder being transported as slaves to the West Indies and Australia, and this was seen as no act of mercy. One of those executed was Sir John Wedderburn of Blackness, who went to his death on 28 November 1746. His son James, having fled to Jamaica, returned to Scotland and settled at Inveresk near Edinburgh, marrying into the Blackburn family. In due course his son, James Wedderburn, became Solicitor General for Scotland and married George and Dorothea’s granddaughter, Isabella Clerk, of whom we have already heard in Chapter 2; we will hear more of the Blackburns and Wedderburns in Chapter 9.

8.9 Commissioner for the Forfeited Estates

After the 1745 rebellion and the ensuing reprisals, most of the Jacobite lords and lairds who had taken part had either fled to the Continent or had suffered death, either in the field of battle or on the scaffold. Their property was, by default, escheat to the Crown. In Scotland, the final number of confiscated estates amounted to forty-one, and covered a vast area of the Highlands (Smith, 1975), so much so that it would have been possible to travel from Kippen in the south-west to Cromarty in the north-east without ever stepping outside it. When an estate or title was forfeit, the king would bestow it upon someone favoured, in reward for their good services, as in 1581 when the 8th Lord Maxwell briefly gained the Earldom of Morton (Chapter 6). But here the scale of things was so immense that this was not possible; for example, the clans living on these estates would be hostile and unmanageable, few trustworthy people could be found there, while any that could be found elsewhere would be unwilling to take on a far-flung and usually debt-ridden estate in ‘the Land of the Mountain and the Flood’.[53] Furthermore, absentee landlords would simply create the sort of conditions that would allow further rebellion to foment.

In those remote areas of Scotland which are generically known as ‘the Highlands’, most of the inhabitants were spread out thinly over rough land from which only a subsistence could be wrought, and many found that stealing cattle offered better prospects. The men, being proud and warlike, were disinclined to do ordinary work. Scores were settled by combat, and feuds between clans endured for generations. Allegiance to one’s laird and clan was supreme, and the Highland laird not only possessed his land, he possessed his people. The following quotation from Prebble (1968) gives a flavour, unpalatable though it may be, of how they lived:

… [southern visitors] were usually disgusted by the houses in which these heroic figures lived, comparing them to cow-byres, to dung-hills … Windows where they existed were glassless … Peat smoke thickened the air … [yet] Each house was an expression of the people’s unity and interdependence.

For the government, the problem was plain enough: the Highlands needed the imposition of ‘civilisation’. Nevertheless, it took them a long time to get round to doing anything about it. In the interim, the Barons of the Exchequer had to deal with the consequences of the forfeitures as best they could, for example, they organised factors to look after the day-to-day running of things and the collecting of rents, but the social circumstances remained unaltered, and if anything disaffection worsened. Rather than face the possibility of a third rebellion, in 1752 the government eventually set up a Commission for the Forfeited Estates[54] with the remit of implementing a document entitled Hints Towards a Settlement of the Forfeited Estates in the Highlands of Scotland (Smith, 1975, Appendix C, pp. 387−390). Although its ideals were liberal and seemingly benevolent, its aims were essentially practical: to bring about a great transformation in the Highlands through the imposition of sweeping changes; the old order had long been at fault and it had to go.

Amongst other things, it recommended: the widespread building of roads, bridges and harbours; suppression of cattle thieving; suppression of tartan and Highland dress except in regimental uniforms; tight control over leases to make sure every tenant would be law abiding; creating villages to provide decent housing and work; and the formation of strategically placed towns where travellers would converge and soldiers could be stationed. Ministers of religion were to be settled in communities and act along with the factors as Justices of the Peace. The general idea was that the income from the estates would be ploughed back in as a means of financing the necessary improvements. It was to be radical social re-engineering, but by and by it would bring about some semblance of normal civilisation.

A survey of the forty-one forfeited estates having been carried out, thirteen were selected as a manageable number to be permanently annexed to the Crown; it was an action gauged to break up the Highlands permanently, for areas with strong Jacobite sympathies would be isolated from each other. The annexed estates would be the easiest to supervise and control, and so they could be prevented from following any clan figurehead that might lead them astray. When a Board of Commissioners surfaced at last in 1755, it was headed by the reformer Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll, otherwise known as Lord Ilay, first governor of the Royal Bank of Scotland (Murdoch, 2004).

In 1764, when the Commission had been going for nine years and Lord Ilay was already dead, George Clerk Maxwell was appointed as one of the Commissioners (Smith, 1975, Appendix D, p. 394). It was just the sort of appointment that would have appealed to him. One of the things he became involved with was the building of the three-span bridge at the head of Loch Tay. This bridge, built by John Baxter[55] in 1774, formed a key component in a route cutting through the Highland glens from Crianlarich in the west to Ballinluig, on the road from Perth to Inverness. George Clerk Maxwell and Lieutenant-General Adolphus Oughton (1719−1780), deputy commander-in-chief of the army in ‘North Britain’, were keen to authorise the project but extra funding had to be requested from the Crown. Clerk and Oughton were involved again in the inspection of the foundation-work. It certainly seems to have been satisfactory, for after 240 years it is still the crossing over the Tay at Kenmore. At least fifty-eight bridges throughout the southern Highlands were funded by the Commissioners (Smith, 1975, p. 304).

Harbour improvements were another concern of the commissioners. George Clerk Maxwell was involved in the work carried out at North and South Queensferry, between which was the principal ferry crossing on the Firth of Forth. John Smeaton estimated £980 for repair work and the erection of new piers to accommodate the ferry. The Board awarded an initial £400 towards the cost and paid out a further £100 based on George Clerk Maxwell’s expression of confidence, in 1776, that good progress was being made (Smith, 1975, p. 330). George also reported on Peterhead harbour proposals.[56]

Before the arrival of canals and railways, getting fuel to the places where it was most needed was always problematic. The provision of decent roads and bridges helped, but in the latter half of the eighteenth century only canals could carry bulk freight at a reasonable cost. As the nascent canal fever in England had not yet spread across the border to Scotland, the Commissioners initially acted by funding surveys seeking out viable canal developments. Some of the ideas they considered would be thought risible today. One such was for a canal from Perth to Coupar Angus. George Clerk Maxwell was satisfied with the engineer James Watt’s conclusion that the project was not worthwhile, but not so with his cost accounting, saying:

[He has a] great share of genius … he is particularly fortunate in arranging his thoughts but [I] am sorry to observe that he is not so good at stating his account. (Smith, 1975, p. 335)

On the other hand, a canal from Loch Fyne through to the Sound of Jura would provide the Clyde fishing fleet much better access to the herring grounds along the Atlantic coast by cutting about eighty-five nautical miles off the journey around the Mull of Kintyre. Over six hundred years before, Magnus Barelegs, King of Norway, had claimed the peninsula of Kintyre from Malcolm III, King of the Scots, by having his men carry his longboat over the narrow neck of land that separates the head of West Loch Tarbert from the fishing village of Tarbert on Loch Fyne. On the face of it, this would appear to be an ideal location for such a canal. Watt was once again engaged to do the necessary surveys (Watt, 1771−73); George Clerk Maxwell duly went through Watt’s report and made his recommendations to the Commissioners.[57] Watt recommended a seven foot deep canal along the longer route from Arisaig to Crinan, and George agreed that, at an estimated £35,000, it would prove the most cost-effective solution and his assessment was accepted by the Commissioners. It was indeed the route that was eventually taken.

By applying themselves to the well-intentioned policies in the guidance document, the Commissioners had started in earnest a process of transforming both the Highlands and its traditional way of life. But even so, the roads, bridges, churches and new settlements affected only a proportion of the population, and so the rest remained wedded to the old way of subsistence amongst the hills. While the Commissioners were working in one direction, many Highland lords and lairds began working in another. Rather than move the indigenous population to the new villages where they could find some sort of work, a look at their account books told them that they would be better off just replacing their tenants with sheep. And so began the saddest and sorriest episode in Highland history, ‘the Clearances’, described so well by Prebble (1982). Nothing that the Commissioners could ever have dreamt of could have been more effective in breaking up the old way of life. From time immemorial the clansfolk had been the lairds’ children, with whom the lairds could do as they pleased, and now it pleased the lairds to forsake them.

Today, much of the Highlands still lies beyond the reach of public roads, and its vast empty regions of mountain and moorland are home mainly to the sheep, the grouse and the deer. Given the immense task the Commissioners faced, it could hardly have come out any differently. An idea of what they did achieve is given in the Appendices of Smith’s thesis (1975) and in Telford (1838). In addition to twenty-three harbour works and fifty-eight bridges (all of which had to be connected up by roads) and the subsidies for canal building all mentioned by Smith, there were numerous disbursements for improvements on a smaller scale. Even after the Commission was stood down in 1784, the spirit of improvement continued, and notably forty-three so-called ‘Parliamentary Churches’ were built at the hands of Thomas Telford in the early nineteenth century.

8.10 The Forth and Clyde Canal

While the Commissioners for the Forfeited Estates were surveying the Highlands, one of the major works going on outside their purlieu was the Forth and Clyde Canal. George Clerk Maxwell, however, was very much involved.

In September 1754 George received an interesting letter from one John Smeaton (1724−1792), then in Edinburgh, telling him that he had obtained the backing of both the Duke of Queensberry and the Earl of Hopetoun for his plan to drain the Lochar Moss in the Maxwell heartlands.[58] He submitted his report to the Duke shortly after writing to George, but nothing came of it (Skempton, 2002, p. 622 & 625; Smeaton, 1754 [publ. 1812]). In the same letter, however, Smeaton mentioned that he had also just delivered his plan for the development of Leith Harbour in response to a Parliamentary Act for the project passed in the previous year. Unfortunately for Smeaton, the Act had neglected to provide the wherewithal to carry out the necessary work, and nothing came of that either. But it was the start of something, for John Smeaton was later involved with Lord Hopetoun, George Clerk Maxwell and the trustees of the Board of Manufactures, to construct a canal from Falkirk to Glasgow with the object of greatly facilitating commerce between the ports on the Clyde and the Forth. Edinburgh, in particular, would then be able to benefit from the riches that were flowing into Glasgow from the new world; sugar, tobacco and cotton. Smeaton delivered his report in 1767 (Smeaton, 1767) and an Act enabling the project was passed in March 1768.

Now, two Commissioners for the Forfeited Estates chose to invest in the canal; one was Lord Elliock (1712−1793), a judge, MP and landowner, and the other was George Clerk Maxwell. Although the route of the canal was south of the ‘Highland line’, and consequently outwith the ambit of the Commissioners there were some who considered the project to be of such great importance that they pressed for money from the Forfeited Estates to be used to subsidise it. It is to the credit of these two Commissioners that this did not happen, and instead the Act required that the initial capital should be raised from 1,500 shares, to be subscribed for by interested parties at £100 each. George Clerk Maxwell went in for five shares, as did his friend the geologist Dr James Hutton (1726−1797), (Perman, 2022; O’Connor & Robertson, 2004a) who had also been involved in promoting the grand design and advising on its route. Both men served on the project’s executive committee from 1767 to 1774, and were amongst those directly involved in the on-site management of works (Daiches et al., 1986, p. 120).

Although Smeaton was able to complete half the work by the end of 1770, he withdrew because of ongoing difficulties with landowners and because the funding was running out. He had another crack at it in 1775, but the money ran out again when the canal was just six miles short of its Clyde terminus (Priestly, 1831). The war with the American colonies that began in the following year and dragged on until 1783 had a double impact; firstly, the cost of the war was a huge drain on the national purse, and secondly, trade with the American colonies and elsewhere was effectively brought to an end. Imports into Glasgow were badly hit so that the income from the completed section of the canal was less than half of what the investors had been hoping for. The project was left in limbo until things recovered after the war. It was at this point, in 1784, that £50,000 was eventually loaned from the Forfeited Estates account[59] to finish the job under a new engineer, Robert Whitworth, who may have previously worked under Smeaton on the Calder and Hebble waterway (Skempton, 2002). Even so, the canal was not finished until 1790 (Groome, 1885). But the money came too late for George, who had by then been dead for several months, and since it had been granted under the 1784 act for winding up the Commission, it could no longer have represented a moral dilemma for the one shareholder to have been on the Commission until the end, Lord Elliock.

George ended up losing out, for by 1775 not only were the canal shares worth only 40 per cent of their original value, there had been extra calls for cash along the way.[60] Amongst other woes regarding his finances, fifteen years of protracted tribulations with the project must have contributed to the deterioration of his health in his final years − something we should bear in mind.

8.11 Commissioner for Customs

Realising that he could well benefit from a boost to his regular income as joint Remembrancer to the Exchequer, in 1762 George Clerk asked for the help of his friend the Duke of Queensberry in finding an administrative post for him, preferably as Postmaster in Scotland. The word ‘friend’ in this context needs to be treated with caution, for their relationship was essentially that of patron and henchman. Just as had been the case between their fathers at the time of the Union of the Parliaments (Chapter 4), friendship under these circumstances could only go so far. However, the Duke turned out to be favourable to the suggestion and sounded out the Prime Minister, Lord Bute,[61] who seemed well disposed to the idea but introduced a note of caution, saying that ways and means would have to be found. The Duke therefore advocated to George that he should make some proposals for improving the revenue so that he might better his chances.[62] George duly complied with the Duke’s request and sent him his observations and ideas on the subject, which Lord Bute was well pleased with.[63] Negotiation about ways and means, however, was still ongoing by the end of the year.[64]

At the start of the following year, the Duke was at his estate at Amesbury.[65] Writing to George, he reassured him that the position was his, and went on to say that when he got back to London he would speak to Baron Mure,[66] a close friend of Lord Bute, in an effort to expedite matters.[67] Despite the Duke’s fairly positive indications, the outcome some two months later was that George was instead offered a position as a Commissioner for the Board of Customs. According to the Duke, Lord Bute thought this post would actually work out better.[68] It certainly carried a useful annual salary of £500, as much as his father had been getting as a Baron of the Exchequer. George wrote back to the Duke expressing his thanks and saying that he would gratefully accept the offer.[69] He received the Duke’s and Duchess’s congratulations a few days later,[70] but having hardly had time to celebrate his good fortune, he received a further letter from the Duke which betrayed the Duke’s true position; he could be charming and helpful, but in the end George was merely his minion. Having got George the post, he was now requesting that he should forgo the salary of £82 10s from his existing post as Remembrancer to the Exchequer. He brushed aside any protest by insinuating that he was asking this out of courtesy, for otherwise someone else would come along and demand it from him. It would understandably have been a slap in the face for George to be treated in this manner, but he stood his ground and told the Duke that he could not afford to comply, stating that he had to put out twice that much on fees for his new post. Unfortunately, we do not know whether the Duke simply dropped his demand or whether he left George no choice in the matter.

In spite of not getting his preferred appointment, George took to his new post of Commissioner of Customs with his characteristic enthusiasm and a determination to make something of it. He started by addressing the problem of smuggling from the Isle of Man, which lies in the Irish Sea some fifteen miles south of Burrow Head on the Mull of Galloway. The nub of the problem was that it was not part of the United Kingdom; back then it was the sovereign property of the Duke of Atholl rather than the British Crown, and as such it was beyond the reach of the excisemen. The level of smuggling from Man into Galloway was such that it seriously curtailed revenue on imports such as rum and brandy. All the smugglers had to do was to get incoming ships to unload their goods on Man and then wait for a suitable opportunity to land the contraband on some remote area of the mainland coast, for which purpose they could use small local craft that would pass unnoticed by day or night. The smuggling was particularly rife along the south-west coast of Scotland which, from the Solway Firth to the Mull of Galloway, forms the nearest landfall north from the Isle of Man.

In 1764 the Prime Minister, George Grenville, tasked the Board of Customs in Scotland to come up with a plan to suppress this illicit trade, and the Board in turn asked George, perhaps because he knew the area around Dumfries, to make a survey of the problem and report back to them. This George duly undertook, but he soon came to the conclusion that not only was the coastline too vast and remote to be effectively patrolled, the local inhabitants were fully complicit in the smuggling. He therefore decided that it would be very difficult to achieve any measure of success by simply trying to suppress it:

… every farmer’s servant who could purchase half a cask of spirits, was engaged [in the smuggling] for his share … the whole inhabitants on the south-west coast … had followed scarcely any other employment than this pernicious traffic. (Clerk, 1788)

The problem needed a radical solution, and he offered one: the government should buy out the sovereignty of Man from the Duke of Atholl. It was a sound idea but an expensive one, and Grenville had a different plan, for he was ready to send out additional naval ships to patrol the seas between Man and the Scottish coast. Although William Craik of Arbigland[71] was not actually a Commissioner of Customs, he was a local inspector that lived near the Solway coast. This position was something of sinecure that gave him status, income and a sizeable share of the proceeds of all seized goods.

He was a friend of George and no doubt one of the first people that George would have consulted about the problem. When the proposal to buy the Isle of Man was made, however, both men went to London to put the case to the government. It seems that George brought Craik to London as a reliable expert witness (Farmer’s Magazine, 1811).[72] After several months of discussion, however, Grenville was at last persuaded that naval patrols would eventually cost more than the purchase of the Isle of Man. Although Man became part of George III’s realm by July 1765, and the Duke of Atholl became £70,000 richer, it retains its own peculiar status as a British Crown dependency (Cahoon, 2014). As to the effect its purchase had on the smuggling, Lord Eldin tells us the eventual outcome:

… the whole inhabitants on the south-west coast … now earn their subsistence by a more honest application of their industry. The face of the country, which formerly never could raise a sufficient quantity of grain to support its own inhabitants, is totally changed. (Clerk, 1788)

A great success perhaps, but we cannot let it pass without mentioning some additional information about William Craik that seems not to have come to George Clerk Maxwell’s notice or, if he did know about it, he was keeping his cards very close to his chest. Kirkbean Heritage Society has in its possession an old letter from an excise officer at Dumfries who, in a report to Edinburgh, stated: ‘Sloop in Arbigland Bay … would not go so far as to say that the Laird was involved … but many of his servants and horses were’ (Blackett, 2010).

The article goes on to assert that Craik was making a fortune out of playing the game on both sides. If George had suspected him, then it may have been the very thing that convinced him that neutralising the Isle of Man was the only way forward; if he did not suspect, then his survey of the problem had failed to get to grips with the real issues involved. Given that the solution he opted for was the right one, there is a fair chance that he did indeed suspect Craik and was playing his own double game in taking him to London to see Grenville!

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

Robert Burns was an exciseman in Dumfries from 1788 to 1796; the smuggling, of course, was still going on. In March 1792 Burns was personally involved in the capture and impounding of the Plymouth schooner Rosamond, which had run aground in the Solway river at Sarkfoot Point, immediately south of Gretna. Sarkfoot is quite far up the Solway, a firth notorious for tidal sands that the smugglers had badly misjudged. But the incident demonstrates George Clerk Maxwell’s contribution to the suppression of smuggling in the region, for there was no longer any point in the smugglers dropping off their wares on the Isle of Man. The master, Alexander Patty, was forced to take his chances by bringing a sizeable ship far up the Solway laden with cargo, and he had paid dearly for it. While he lost both his ship and his cargo, he at least managed to escape the gallows. After putting up a stiff resistance involving several exchanges of cannon fire, he and his crew were able to get over the side of the vessel and make it along the treacherous sands onto the English coastline, where they soon disappeared (Burns Encyclopaedia, 2014).

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

In his time at the Board of Customs, George worked closely with two particularly interesting people. The first was an ex-soldier, Basil Cochrane (1701−1788)[73] who had also been appointed a Commissioner in the same year, 1763. Cochrane was the great-uncle of the journalist James Boswell, but more interestingly, in his military capacity he had been governor of the Isle of Man from 1751 to 1761, which makes it a bit harder to believe that the purchase of Man had been entirely George Clerk’s idea. The other interesting party was none other than Adam Smith (1723−1790), author of the Wealth of Nations. Appointed as a Commissioner in 1778, Smith was also a friend of James Hutton and, along with Joseph Black, George Clerk Maxwell and his younger brother John Clerk of Eldin, they were members of the Oyster Club that met regularly to dine and converse in an unobtrusive Grassmarket tavern.[74]

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

In the Correspondence of Adam Smith (1987, pp. 405−412) there appears an account of a remarkable incident that took place off the Scottish coast in September 1779, during the War of Independence with the American colonies. The account comes to us via Smith because the Commissioners at the Customs House in Edinburgh[75] had been particularly tasked to keep an eye out for any such occurrence, and four ‘French’ warships had been seen out at sea somewhere between Dunbar and Eyemouth. Commissioners Adam Smith, George Clerk Maxwell and Basil Cochrane were in attendance, and they duly alerted the shipping in the Firth of Forth to the danger. On 16 September they sent a customs cutter out to reconnoitre, and it seems that her captain got within ‘a pistol-shot’ of what he took to be a fifty-gun French warship off the Isle of May;[76] in reality it was the 42-gun colonial Continental Navy warship Bonhomme Richard [77] under the command of Captain John Paul Jones (1747−1792). Jones was a native of Kirkcudbright and, coincidentally, the son of a gardener on William Craik’s estate at Arbigland. Born plain John Paul, he became a merchant sea captain. He later fled to Virginia after killing one of his crew, and changed his name to cover his tracks. When the War of Independence was declared, Jones did not hesitate, and in a few short years he was in command of a colonial frigate and back in British home waters looking for a fight.

The captain of the cutter briefed Clerk Maxwell and Smith on the situation and although they gave orders for three revenue cutters to be placed in readiness, Jones did not sail up the Forth. Instead he engaged the British Baltic merchant fleet a week later and claimed his first great naval victory, thereby earning himself the title of ‘Father of the United States Navy’ (Potts, 2011).

8.12 Mineral Spas and Mining

George Clerk Maxwell was ever interested in what the land could be made to produce, and its natural resources were no exception. In his sketch of George, Lewis Campbell portrays him thus:

We find him, while laird of Dumcrieff … practically interested in the discovery of a new ‘Spaw’ [spa] and humoured in this by his friend Allan Ramsay, the poet:– by and by he is deeply engaged in prospecting about the Lead Hills, and receiving humorous letters on the subject from his friend Dr. James Hutton. (C&G, p. 18)

From an early age, George would have taken part in his family’s annual peregrinations to take the goat’s whey and the spa waters for the benefits of their health (see §6.6 and §6.9). He would therefore have been well acquainted with spas both as a source of public benefit and as a means of making money. A letter from the Duke of Queensberry[78] provides some detail concerning George’s involvement with the recently discovered ‘spaw’ on the slopes of Hart Fell, about three and a half miles north of Moffat.[79] Being on the Duke’s land and near Dumcrieff, the Duke would have been certain to get George busy on it. Indeed so, for it was over a mile from the nearest track, not to mention a considerable uphill climb. In 1753, George visited the spa and offered to help with making a better access road. The entrance to the well also needed shoring up with some stonework to prevent it from becoming blocked. While the Duke was prepared to spend £30 on the work, in laying out such a sum he would have had the health of his coffers in mind rather than the health of the populace, for such healing waters could be bottled and sold.

Each spa was associated with a specific range of benefits as indicated by its characteristic chemical composition. There was consequently a great deal of interest in seeing what a newly discovered spa could offer. The new spa in question may have been awkward to get to, but there would always be people eager to try it in the hope that it might be just the one for them. As it turned out, the Hartfell spa was of a complementary composition to the local Moffat waters, for it contained salts of iron rather than calcium, and it was still rather than effervescent. It had been discovered in 1748 by a local eccentric, John Williamson,[80] who is said to have been involved in some mine workings nearby (Groome, 1885, vol. 3, p. 248). Although Williamson would have needed the water for the mine works, it appears that he did not start to take it regularly until 1751, when he noticed that it relieved a persistent stomach problem (Horsburgh, 1754).

Although the water at the Moffat Well could be taken away in bottles for later consumption, it was effervescent and did not keep so for long. The new spa had the commercial advantage that, being still, the bottled water could be kept more or less indefinitely, meaning that it could be distributed to a much wider market. Seeing such an opportunity, the Duke suggested building a well-house in the following year. The undertaking of such projects made people like George useful to the Duke, and in return, it would be hoped that he would help them, as George knew only too well.

The Duke was as good as his word, for in Horsburgh (1754, p. 1) we find the footnote:

… his Grace the Duke of Queensberry … was, for the public benefit, generously pleafed to give money to make a convenient road ; and to build a fhade or arch over the fpring to preferve it from dirt and rubbifh …

The bottled product was even exported to the West Indies (Turnbull, 1871), from which trade the Duke may have benefited from a percentage, as he did with his mines. Turnbull also mentions that George was the one behind the erection of a memorial to Williamson over his grave in Moffat churchyard:

In Memory of Jno. Williamson, who died 1769,

Protector of the Animal Creation,

The Discoverer of Hartfell Spa, 1748:

His life was spent in relieving the distressed.

Erected by his friends, 1775 (Turnbull, 1871, p. 101)

Indeed, George had been Williamson’s friend and fellow traveller in prospecting for spas and minerals. In fact, he was ‘as great an enthusiast in mineralogy as Williamson, and what is more, as little successful in his theories and operations’ (Ramsay, 1888, p. 335).

The bulk of John Ramsay’s account appears to be first-hand, and his visits to the area are contemporaneous; he would therefore have been in a very good position to take note of what was being said about George Clerk Maxwell’s reputation in that sphere of activity, that is to say prospecting and mining. Gray (BJC, p. 96n1) said of George: ‘he also set on foot various mining schemes for lead and copper, through some of which he suffered great loss’. It is perhaps because of this purported lack of success that there is little said about what he actually did achieve; it is important that we should explore this, for George did run into a severe financial crisis during the last few years of his life. How then did it come about?

(By courtesy of Dumfries and Galloway Libraries Information and Archives (local studies collection: CO003976. Photograph J J Byers))

George’s interest in mining came naturally; firstly he was interested in just about anything that was either agricultural or industrial, and secondly, mining was in his blood. His brother James mined coal at Loanhead, as did their father, the Baron, and their grandfather, the 1st Baronet (Chapter 4) before them. In addition, in 1739 the Baron went out of his way to see how coal was hewn from under the sea at Whitehaven, and he was called on by his patron the Duke of Queensberry to inspect his mines at Wanlockhead (BJC, pp. 153, 165, 175). As far back as 1718, he and his father had also had their own designs on mining for minerals rather than coal. He says that they went to Leadhills, ‘to view the Lead works belonging to the Earl of Hop[etoun], for we had then a design of purchessing the lands of Glendorch in the nighbourhood’ (BJC, p. 97).