Brilliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

3.2 The First Clerk of Penicuik.

3.3 The First Baronet of Penicuik

3 The Early Clerks of Penicuik

Our history of the Clerks of Penicuik from the time of Mary, Queen of Scots to the middle of the eighteenth century is mostly contained in the original manuscript of a personal memoir written by Baron Sir John Clerk, 2nd Baronet of Penicuik,[1] which bore the admonition:

This book may be read by all my friends in the House of Pennicuik,[2] but is never to be lent or carried out of the House.

Nevertheless, about 1890 the Dowager Lady Clerk gave her permission for it to be published by the Scottish History Society (Clerk & Gray, 1892, hereinafter referred to as BJC). The Clerk history recorded by the Baron was briefly recapitulated and updated by Miss Isabella Clerk, a daughter of Sir George Clerk, 6th Baronet of Penicuik, for the use of Lewis Campbell in his 1882 Life of James Clerk Maxwell. Campbell also added material from a book of autograph letters which was then in the possession of James Clerk Maxwell’s widow, Katherine Dewar. Finally, local Penicuik historian John J. Wilson provided a history of the Clerk family in his Annals of Penicuik (1891, pp. 150−164). While he gives no specific attribution for his sources, Wilson was involved with the Scottish History Society in gaining access to the Baron’s manuscript. Beyond this, the archives held at NRS help to fill in some of the gaps and also provide some interesting details.

3.1 The Origins of the Clerks

According to the Baron’s memoir, the Clerks of Penicuik are descended from John Clerk of Killiehuntly (1511−1574). Killiehuntly and the Dell of Killiehuntly lie about two miles to the east of Kingussie, by the banks of the River Tromie not far where it meets the mighty Spey. This is in the very heart of Scotland in a region that was in ancient times called Badenoch, the purlieu of the Duke of Gordon. However, that was not their original seat, for Clerk is not a highland name. Douglas (1798) suggests that the Clerks had been prominent citizens of Montrose on the east coast of Scotland since the fourteenth century. They later gained lands in Fettercairn, about ten miles to the north-east of Montrose, and those of Killiehuntly, which even by the shortest route is some ninety miles distant and over mountainous terrain. In being a loyal supporter of Mary Queen of Scots, John had gone against his feudal superior the Duke of Gordon, and so had to abandon his Badenoch estates in 1568 when the ill-fated queen eventually quit her kingdom never to return. Things had gone badly for her and her adherents, and they would get worse.

Despite this setback, John’s son, William Clerk, was a prosperous merchant in Montrose during the latter part of the sixteenth and early part of the seventeenth centuries. Of him we know little more other than that he died in 1620.

3.2 The First Clerk of Penicuik

William Clerk’s son, John (1611−1674), was a merchant like his father and proved to be a very able one indeed. Having moved to Paris in 1634 in the hope of making his fortune, by good commercial prowess he managed to succeed in his goal to the extent that, when he returned to Scotland in 1646, he was able to purchase, piece by piece, the extinct baronetcy of Penicuik lying on the River North Esk some ten miles south of Edinburgh. Nowadays Penicuik also refers to the dormitory town that serves that city. Having been a mere hamlet when the first Clerk arrived on the scene, by the middle of the nineteenth century it had grown into a busy little town with three paper mills and a coal mine. The Penicuik estate itself lies astride the River North Esk between the Peebles and Carlops roads, just to the south-west of the town.

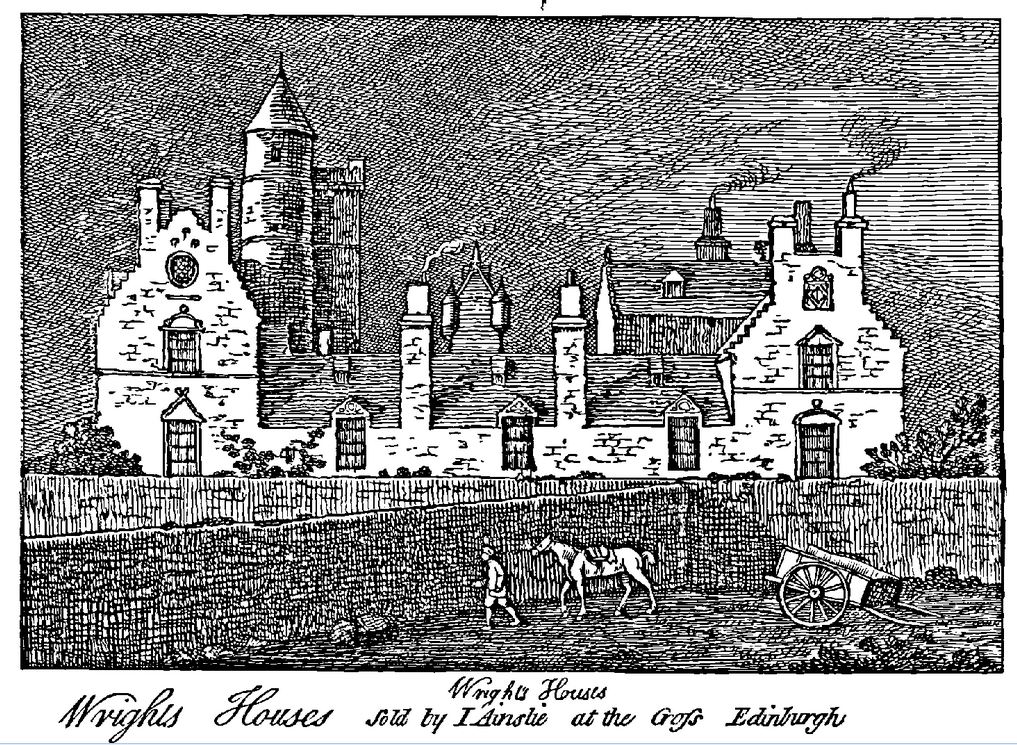

John Clerk also purchased the ancient lands of Wrychtishousis, or Wright’s Houses (Wilson, 1886, p. 432), then a substantial property just outside Edinburgh on the road south to Penicuik, Figure 3.1. He married Mary Gray, daughter of Sir William Gray of Pittendrum, whose grandmother had been a lady-in-waiting to Mary, Queen of Scots (Family Tree 1), and who had left her some pieces of gold jewellery that was given to her by that ill-fated queen before her execution in 1587.[3]

These buildings on the north-east edge of Bruntsfield links were later engulfed by tenement buildings. The Golf Tavern,[6] which potentially dates from 1456, still remains.

John Clerk left his Penicuik estates to his first son, also named John, who became 1st Baronet of Penicuik, and to his second son James he gave Wright’s Houses. A third son, Robert, became a surgeon in Edinburgh; he saved the life of his nephew, the first Baronet’s eldest son, without whom this story would never have taken place, and it was also from this Robert Clerk that descended another prominent branch of the family, the Clerks of Listonshiels and Rattray.

Of John Clerk’s daughters, Margaret married William Aikman of Cairnie;[4] their son, William Aikman (Robinson et al., 1798), was the well-known artist who painted the portraits of the 2nd Baronet and of his friend, the poet Allan Ramsay. John Clerk’s youngest daughter Catherine, born in 1662, married Sir David Forbes of Newhall,[5] not far from Penicuik, where William Clerk, John Clerk’s grandson, and Allan Ramsay were frequent guests; they will enter our story in Chapter 5.

3.3 The First Baronet of Penicuik

John Clerk of Penicuik’s eldest son was also called John (1649−1722). This John Clerk had both the wealth and good fortune to be created a Baronet of Nova Scotia by King Charles II at the age of thirty. Since he is the third John Clerk encountered thus far, it will be helpful to differentiate them as being respectively John Clerk of Killiehuntly, John Clerk of Penicuik, and John Clerk 1st Baronet of Penicuik. This particular type of baronetcy had been instituted by Charles’ grandfather James VI [7] for the purpose of settling the colony of Nova Scotia. The new baronets were required to sponsor settlers there, or to pay an equivalent amount of money to the Crown, and so a wealthy landed gentleman who was lacking a hereditary title could become a baronet provided that he was a loyal subject, had a decent lineage, and was prepared to make the necessary financial contribution to the exchequer. In this manner, therefore, the existing Baronetcy of Penicuik was created. One of the ancient and seemingly arcane duties of the previous line of Penicuik baronets was that whenever the King went hunting on Edinburgh’s Burgh Muir (which name is recalled by the present-day district of Boroughmuir), he had to sit on the Buckstone (which likewise gives its name to an Edinburgh suburb) and ‘wind three blasts of a horn’. After 1603, visits to Scotland by the British monarch were very rare indeed, and by the time that this situation was set to rights, most of the Burgh Muir was houses and parkland; it is therefore unlikely that any of the baronets was ever called upon to do this for real. Nevertheless, it is still part of the Clerk motto, ‘Free for a Blast’.

The 1st Baronet did, however, take his other duties as a landowner seriously, for he became the member representing Edinburgh in the Scottish Parliament, and a lieutenant-colonel in the Earl of Lauderdale’s regiment. Lauderdale had been for the Covenanter cause,[8] but when he saw the monarchy under threat, he effectively changed sides and became a Royalist. Having tried in vain to save Charles I from defeat, he was imprisoned and had his estates confiscated by Cromwell. At the Restoration, however, his fortunes were once more in the ascendant and he was one of those included in the party that went to Breda in 1660 to bring Charles II back to his ‘rightful place’. As for John Clerk, Charles II would have granted him a baronet’s letters patent only if he were certain of his loyalty, for in 1679 the Covenanting troubles in Scotland still dragged on. The battle of Rullion Green had taken place in 1666 on John’s own back doorstep, and the uprising at Bothwell Bridge in 1679, though further afield, occurred in the very year of his grant. We must surely therefore see John Clerk as leaning towards the Royalist cause rather than that of the rebellious Covenanters. Having sympathy with the Stuarts would be consistent with the loyalist leanings of his great-grandfather and, indeed, his connection with Lauderdale serves to confirm it. However, the Baronet did like many others and kept his political and religious loyalties close to his chest, for had the tide turned so overwhelmingly against the present king as it had done against Charles I, the Baronet could have found himself in great difficulty. As it turned out, the ousting of James VII in 1689 in favour of William and Mary led to the abolition of bishops in the Church of Scotland, settling religious tensions and eventually bringing the Covenanting troubles to an end.

The Baronet saw action of a different kind when sixteen robbers attacked his residence at Newbiggin,[9] on the night of 17 December 1692. He managed to fend off his assailants until some of his tenants were able to come to his aid. Having made off with a few pieces of silverware, the robbers were eventually caught and prosecuted.[10] It is hard to imagine that, being an officer in Lauderdale’s regiment, he never took part in any action against the Covenanters. Perhaps some of them who were still beyond the law were minded to settle old scores? Was the assault on Penicuik House such a case? It seems to have been a large party for the assailants to have been simply robbers, and more likely they were out to make some such trouble.

The Baronet married Elizabeth Henderson in 1674. She was the daughter of Henry Henderson, or Henryson, of Elvingston near Haddington, and they had three sons and four daughters, who were:[11]

- John (1676–1755), who was his successor

- Elizabeth

- Henry ( –1715), ‘bred to sea’, and close friend of his brother John [12]

- Barbara (1679–1734), who married first John Lawson of Cairnmuir,

then secondly Dr William Arthur, King’s Botanist and keeper

of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh (BJC, p.120, n1) - William (1681–1723), an advocate, who it was that ended up playing

the crucial role in the Clerk Maxwell succession - Sophia

- Mary, who married the Rev. Alexander Moncrieff of Culfargie,

minister of Abernethy, in 1722.

Elizabeth Henderson died at the age of twenty-five (BJC, p.8). If so, she must have been about eighteen at the time of her marriage and had had a child almost every year. From the same source we hear that after about ten years as a widower the Baronet married again in September 1692, to Christian Kilpatrick, who bore him eight more children, making fifteen in all:

- James, who became the general inspector of the outposts of North Britain

- Catherine

- Christian

- Robert (1702–1761), who was from 1732 a commissary in Edinburgh[13]

- Margaret

- David

- Hugh (1709–1750) a merchant who traded with North Carolina

- Alexander, a painter ( –1775).

With such a large family, Sir John decided that it would be fitting to build a family mausoleum at St Mungo’s in Penicuik; although there is no longer any access, it still stands.[14] Following his death on 10 March 1722 he too was buried there. Around the time of his daughter Mary’s wedding he had been beginning to feel quite weak, which in these days was not in itself remarkable considering he was then about seventy-three years of age. Leaving his family to enjoy the rest of the wedding celebration, he retired to his bed early to read by the light of a candle, and for a time did so. All the while, his wife and daughters came and went from the room, always taking care not to disturb him. When his wife finally came to bed, however, she found him apparently still reading, but not so, for Sir John Clerk, the 1st Baronet of Penicuik, had passed away some hours before, in complete tranquillity, without anyone being aware that he had gone (BJC, p. 108−109). The peaceful manner of his passing was something that ‘he always wisht for, euthanasia [a pleasant death]’ (BJC, p. 9). The line of descent from the 1st Baronet of Penicuik down to James Clerk Maxwell is to be found in Family Tree 2.

Notes

[1] Baron and baronet are separate titles (see Glossary). Since the second Baronet is frequently referred to simply as ‘the Baron’ we shall do the same.

[2] One of many variations in the old spelling of the name

[3] Known as the ‘Penicuik Jewels’ (NMS: H.NA 421 and H.NA 422). According to Wilson (1891, pp. 150‒151) they comprise a gold necklace and pendant locket that were bequeathed by Mary Queen of Scots to one of her servants, Egidia (Giles) Mowbray, the great-grandmother of Mary Gray (Family Tree 1).

[4] Near Arbroath, in what was then Forfarshire.

[5] See Burke (1834‒38, vol, 4, p. 621) and Grant (1944, p. 73). The Newhall estate lies a little to the south-west of the Penicuik estate.

[6] CANMORE: ID 128511

[7] Because of the Scottish context of this book, it will be simpler to write ‘James VI’ rather than ‘James VI and I’, and likewise ‘James VII’ rather than ‘James VII and II’

[8] The Church of Scotland had bishops until they were abolished in 1689. The Covenanters were stalwartly opposed to the principles and practices of episcopacy whereas the King pressed in the opposite direction with measures designed to bring the Church of Scotland closer to the Anglican Church, of which he was the head. Wishing at all costs to prevent this, the Covenanters banded together under the Scottish National Covenant that was signed in 1638 by all the chief adherents to the cause. This was reiterated in 1643 by a treaty with the English Parliament in the form of the Solemn League and Covenant. There ensued a period of political and religious strife, rebellions and wars during which covenanters were greatly persecuted. It did not end until James VII quit the throne. (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2013; M‘Crie, 1841).

[9] Newbiggin, or Newbigging, was the the original Penicuik House, which was ‘close behind’ the later structure built by James, 3rd Baronet, in 1761. A bigging was a house or home, and so, ironcally, Newbiggin, ‘the old house’, had itself been ‘the new house’, suggesting that there had been an even earlier one.

[10] NRS: GD1/1432/1.62, eighteeenth century

[11] Foster, 1884; BJC, 1892; Seton, 1896, pp. 592, 911‒12 .

[12] NRS: GD18/5218, Letters to and from Sir John Clerk…1698−1708.

[13] Later Robert Clerk of Colinton, he qualified as an advocate in 1725 and married Susan Douglas (Grant, 1944; Foster, 1884, p. 53; and Douglas, 2013).

[14] CANMORE: ID 51652