Brilliant Lives

by John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

A17.1 Maxwell’s Innovative Method for Drawing True Ovals

A17.2 Awards and Commemorations For James Clerk Maxwell

A17.3 James Clerk Maxwell’s Legacy to Science and Mankind

A17.4 The Birth Dates of George and Dorothea’s Children

A17.1 Maxwell’s Innovative Method for Drawing True Ovals

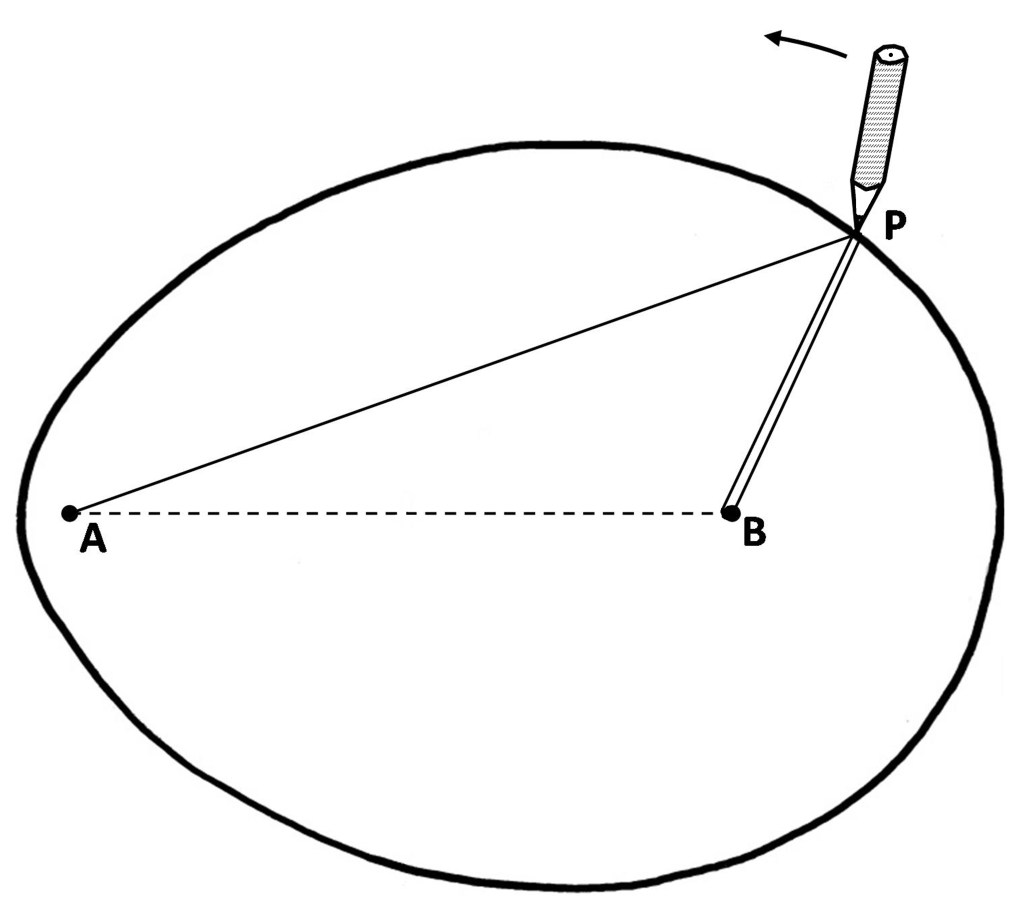

The conventional method for drawing an elliptical oval is shown in Figure A1.1

Figure A1.1 : Conventional Method for Drawing an Elliptical Oval

Here the thread is tied to pins A and B while P, the point of the pencil, is pulled outward so as to make the thread tighten so as to keep it on the curve that makes AP plus PB constant and equal to the length of the thread. Maxwell’s ingenious idea involved wrapping the thread back on itself, as the rope does in a block and tackle, so that when the pencil moves, more thread will now pass round it on one side than on the other. The simplest form, shown in Figure A1.2, has the thread tied to the pencil point P then looping round pin B and sliding round P again before being finally tied at A. The result is shown is shown in Figure A1.2.

Figure A1.2 : Maxwell’s innovative method for drawing a general oval

With the string is looped once round pin B and terminating at P the a truly egg-shaped oval is produced.

A17.2 Awards and Commemorations For James Clerk Maxwell

Prizes and Honours [1]

- 1846 Prize Medal for Successful Competition in Geometry, Edinburgh Academy, Class 5

- 1847 Mathematical Medal, Edinburgh Academy, Class 6

- 1851 Smith’s Prize, Cambridge Mathematical Tripos (shared)

- 1857 Adams Prize, University of Cambridge

- 1856 Fellow, Royal Society of London

- 1860 Rumford Medal, Royal Society of London

- 1861 Fellow, Royal Society of London

- 1866 Bakerian Prize Lecture, Royal Society of London

- 1869 Keith Medal, Royal Society of Edinburgh

- 1870 Honorary LLD, University of Edinburgh

- 1874 Foreign Honorary Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences of Boston

- 1875 Member, American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia

- 1875 Corresponding Member of the Royal Society of Sciences of Gottingen

- 1876 Honorary DCL, Oxford University

- 1876 Honorary Member, the New York Academy of Science

- 1877 Member of the Royal Academy of Science of Amsterdam

- 1877 Foreign Corresponding Member, Mathematico-Natural-Science Class of the Imperial Academy of Sciences of Vienna

- 1878 Volta Medal and Honorary Doctor of Physical Science, the University of Pavia

Plate A2.1 : Maxwell’s Prize Medals

(Left to Right) Rumford Medal of the Royal Society of London (1860), Volta Medal of the University of Padua (1878), Keith Medal of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1871). (By courtesy of the Cavendish Laboratory)

Commemorations [2]

- James Clerk Maxwell Statue, George Street, Edinburgh

- Maxwell (abbreviation Mx), the CGS unit of magnetic flux

- Maxwell’s displacement current, a concept which completed electromagnetic theory

- Maxwell’s equations, for the electromagnetic field

- Maxwell’s electromagnetic stress tensor

- Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, of the velocities of molecules in a gas

- Maxwell’s Demon, a well-known thought experiment originated by Maxwell but named as such by Lord Kelvin

- Maxwell relations, thermodynamic equations

- Maxwell, an asteroid

- Maxwell Montes, a mountain range on Venus

- The Maxwell Gap, in the rings of Saturn

- Maxwell, a crater on the Moon

- The James Clerk Maxwell Building at King’s Buildings, University of Edinburgh

- The James Clerk Maxwell Building at Waterloo Campus, King’s College, London

- The Maxwell Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Edinburgh and Heriot Watt Universities (jointly), Edinburgh

- The James Clerk Maxwell Centre at Edinburgh Academy

- The Maxwell Building, Science Park I, Singapore

- Maxwell Centre for the Physical Sciences, New Cavendish Labs, Cambridge

- James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, Hawaii

- James Clerk Maxwell Prize for Plasma Physics, American Physical Society

- James Clerk Maxwell Medal, IEEE, RSE

- James Clerk Maxwell Foundation, 14 India Street, Edinburgh

- James Clerk Maxwell Statue, George Street, Edinburgh

- James Clerk Maxwell Memorial, Parton Parish Church.

- The Clerk Maxwell Lecture, Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET)

- Glenlair Preservation Trust, Glenlair (restoration of Glenlair House)

- Commemorative plaques at his residences in Edinburgh, Aberdeen, London and Cambridge, and at Old College, Edinburgh University, and the Cavendish Laboratory

- Commemorative postage stamps by San Marino and Mexico, and a souvenir sheet by the Republic of Mali

- Tributes from Albert Einstein and Richard Feynman as to him being one of the greatest ever scientists

The 17 scientists and engineers appearing in the BBC 2002 poll of the ‘100 greatest ever’ Britons are given as:[3]

- 2. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, (1806–1859)

- 4. Charles Darwin (1809–1882)

- 6. Sir Isaac Newton (1643–1727)

- 20. Sir Alexander Fleming (1881–1955)

- 21. Alan Turing (1912–1954)

- 22. Michael Faraday (1791–1867)

- 25. Professor Stephen Hawking (1942–)

- 42. Sir Frank Whittle (1907–1996)

- 44. John Logie Baird (1888–1946)

- 57. Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922)

- 65. George Stephenson (1781–1848)

- 78. Edward Jenner (1749–1823)

- 80. Charles Babbage (1791–1871)

- 84. James Watt (1736–1819)

- 91. James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879)

- 95. Sir Barnes Wallis (1887–1979)

- 99. Sir Tim Berners-Lee (1955–)

A17.3 James Clerk Maxwell’s Legacy to Science and Mankind

As we have seen, Maxwell made many great contributions to science, but if we had to choose the one that has had the greatest impact on our lives today, we must single out his work on the foundations of electromagnetic theory. It eventually resulted in the development of a technology that almost every person today finds indispensable. In addition, it enabled Albert Einstein to make his great leap forward with the theory of relativity. The history of the world since about 1900 would have been completely different were it not for these two great pillars of modern physics, electromagnetic theory and the theory of relativity.

By the eighteenth century the subject of mechanics was well developed, and while there had been some study of electricity and magnetism little of it could be put to practical use. By the early nineteenth century, work on electromagnetism, that is to say, magnetism produced by electric currents rather than magnetic materials, was just beginning, and by the middle of the century it was still incomplete. On the other hand thermodynamics, the theoretical study of which involves such things as how heat can be most effectively turned into work, was therefore of great interest and being applied to the further development of the key invention of the industrial revolution, the steam engine. Maxwell’s friend Sir William Thomson was at the forefront of was at the forefront of this research, from which came some fundamentally important physical revelations, for example: work can be readily turned into heat whereas the same amount of work cannot be recovered from that heat; perpetual motion is impossible; heat only flows from a hot body to a colder one, and never vice versa without work being done (see ‘Maxwell’s Demon’ in §2.7). By the end of the 1850s electromagnetic theory had some catching up to do, but James Clerk Maxwell had already been at work on the ideas of Michael Faraday.

Electricity and magnetism had long been known as separate subjects until the year 1820, when Hans Christian Oersted discovered that an electric current creates a magnetic field. So began the study of electromagnetic phenomena. In 1832, Michael Faraday had also discovered that a changing magnetic field gives rise to an electric one. By then, the working knowledge of electromagnetism was such that William Sturgeon had invented the first practical electrical motor (Day & McNeil, 1996, pp. 1178−1179) and Hippolyte Pixii the first dynamo, a type of electrical generator (ibid, p. 970). James Clerk Maxwell would have been inspired by seeing an exhibition of such things in 1842 when he was a boy at school in Edinburgh. A theoretical understanding of the subject was only then nudging along in piecemeal fashion with major contributions from Andre-Marie Ampére, Jean-Baptiste Biot, Félix Savart and again Michael Faraday, all of whom have given their names to various aspects of the subject.

Although it did not appear in print until 1864, James Clerk Maxwell’s first essay on the subject, ‘On Faraday’s Lines of Force’, was given in December 1855 and February 1856 to the Cambridge Philosophical Society, when he was just twenty-four years old (Maxwell, 1864a). The paper opens with the observation, ‘The present state of electrical science seems peculiarly unfavourable to speculation’, which of course indicated that the situation was particularly favourable for further enquiry by Maxwell himself! For him it was just the beginning, and by 1861 he had published the first part of a major four-part paper, ‘On Physical Lines of Force’ (Maxwell, 1861−62), in which he drew together the known laws of electricity and magnetism as they stood at the time and, by way of a mechanical analogy, attempted to explain how a material (generally called a medium) could carry and transmit electrical charges, currents and forces. Although this formulation of the theory was able to support the existence of electromagnetic waves and, indeed, to identify light as being a form of electromagnetic wave, his mechanical analogies were taken too literally, and he therefore decided to abandon them and republish his findings based on the concept of electromagnetic fields which, being abstractions, could not be denounced as being improbable or unrealistic. In 1864, almost nine years to the day after presenting his first paper on the subject, he read ‘A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field’ to the Royal Society of London (Maxwell, 1865). The major equations and conclusions were the same as before, but this time the paper was accepted and in due course it became the cornerstone of modern electromagnetic theory.

But if Maxwell had merely drawn together the laws of electromagnetic theory as they stood at the time, he would not have achieved this at all. In picking out the distinct laws that are essential to the theory, he chose in particular to consider what constitutes an electrical current. It was then held that an electrical current was the result of a flow of electrical charges around a circuit, something which must be familiar to almost everyone today, when we can flick a light on with a switch that completes a circuit to let the current flow; we can also see the effect of the current on the light-bulb filament, which glows bright from the heat created by the frictional effect of the filament wire on the current flowing through it. But now Maxwell was thinking more generally, and took the view that any motion of electric charge would constitute a current, irrespective of whether or not it was able to move around a complete circuit.

His rationale was that even insulating materials like glass or amber contained electrical charges imprisoned, as it were, within them, for charge could be taken away from their surface simply by friction, say by rubbing them with a cat’s fur. If such an insulator were placed in an electric field, for example by placing it near some charge that had been collected in this way, the charges trapped within the insulator would be attracted or repelled and, despite not being able to flow freely to the surface, they would nevertheless be displaced to some small degree. But any motion involved in that displacement is only a momentary thing, so that the displacement itself reaches a limit and cannot therefore constitute an ongoing current. However, what would happen if the applied electric field were then to be reversed in direction? By that time it was well known, from Faraday’s law of induction, that a rotating magnet would not only produce an alternating magnetic field along a given direction, that is to say one that continually reverses in direction in time with the rotation of the magnet, but also an alternating electric field. Maxwell reasoned that his displaced electrical charges within the insulator would follow the alternating electric field and would be displaced first in one direction and then the other, so forming an alternating current:

This displacement [itself] does not amount to a current, because when it has attained a certain value it remains constant, but it is the commencement of a current, and its variations constitute currents’ (WDN1, p. 491).

In a normal steady current, or direct current, charges flow continuously, for example, round a loop of conducting wire. In an alternating current, however, they need only vibrate back and forward without giving rise to a continuous flow. Maxwell called his new sort of current a ‘displacement current’, and he must have had great satisfaction in noting that, like any other current, it would give rise to a magnetic field. This was a new phenomenon that no one before Maxwell had ever considered, and so it necessitated a change to the electromagnetic equations as they were then known. The entire concept came to him as a result of thinking deeply about what must happen when molecules in an insulating body are subjected to an electric field, and even although his resulting insight was simple, it was a turning point; so much so that it was in effect the key to the mystery: what is light?

While it was known that light was likely to be some sort of wave, until then there had been no clear idea as to what sort of wave it might be. In 1846 Michael Faraday had speculated that it might be some sort of ‘vibration in the lines of force which … connect particles’ (Faraday, 1846), which was at least suggestive of an electromagnetic wave and may have given Maxwell some clue as to what he was looking for. Having found the key, it did not take him long to unlock the answer: electromagnetic waves.

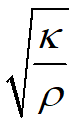

The discovery of the displacement current allowed Maxwell to manipulate his electromagnetic equations into what is called a ‘wave equation’. Wave equations were already well known, and whether they describe sound waves, the vibrations of a string, or the waves on a pond, they all have the same simple, characteristic form. To this extent, at least, electromagnetic waves are no different. Once the wave equation has been found, the velocity of the wave in question is readily determined. In the case of sound vibrations, the velocity of the wave, that is to say the speed of sound, is found from the ratio of the stiffness of the material κ to its density ρ, and in fact it is equal to the square root of that ratio,

The velocity of electromagnetic wave turns out very similarly, except that the velocity is equal to

in which the constant ε indicates how much of Maxwell’s displacement is induced in the medium by a given electric field, whereas μ relates to the degree of magnetisation induced in it by a magnetic field. Seeking the data for air as the medium, Maxwell was profoundly struck by the fact that Kohlrausch & Weber (1857) had not only already measured both ε and μ, but had gone so far as to note that  was equal to 311 million metres/second, which more or less matched Fizeau’s most recent result for the speed of light in air, 315 million metres/second. Now, nothing in the ordinary world travels at such a speed. The speed of sound in air is only some 300 metres/second, and it may have been known that in metals and fused quartz it could reach 6,000 metres/second, but even so the speed of light is some 50,000 times greater, making it unique. Surely it could not be the case that the speed of electromagnetic waves was so close to the speed of light and yet there be no connection between the two? Whereas Faraday had speculated on the possibility, Maxwell was now convinced that light must be an electromagnetic wave, a thrilling conjecture that in the course of time has become a matter of fact.

was equal to 311 million metres/second, which more or less matched Fizeau’s most recent result for the speed of light in air, 315 million metres/second. Now, nothing in the ordinary world travels at such a speed. The speed of sound in air is only some 300 metres/second, and it may have been known that in metals and fused quartz it could reach 6,000 metres/second, but even so the speed of light is some 50,000 times greater, making it unique. Surely it could not be the case that the speed of electromagnetic waves was so close to the speed of light and yet there be no connection between the two? Whereas Faraday had speculated on the possibility, Maxwell was now convinced that light must be an electromagnetic wave, a thrilling conjecture that in the course of time has become a matter of fact.

By bringing all of the then known electromagnetic equations together with his particular new idea of electrical displacement, James Clerk Maxwell laid the foundations of a set of four equations now known after him as ‘Maxwell’s equations’. It fell to four significant others to complete what he had started: Oliver Heaviside, Heinrich Hertz, Hendrik Lorentz and Albert Einstein. Heaviside reduced Maxwell’s somewhat ungainly original equations to pretty much the same form that is in use today; in 1887 Hertz provided the experimental verification that electromagnetic waves did indeed exist; and by the beginning of twentieth century Lorentz had given Maxwell’s theory a proper microscopic basis, the very thing that Maxwell had attempted to explore with his mechanical analogies of 1861. Finally, Einstein showed that Maxwell’s equations were in complete agreement with special relativity.

As to the practical benefits to follow from Maxwell’s work, although Sir Oliver Lodge was granted a US patent on signalling with radio waves in 1894, it was Guglielmo Marconi who made wireless telegraphy a practical reality in the final years of the nineteenth century, nearly forty years after Maxwell had first mooted the electromagnetic wave.[4] For Marconi, it was just the beginning, for it had occurred to the British admiralty that if wireless telegraphy could be made to work over large enough distances then it would revolutionise their ability to command and control their huge fleet. Consequently they took great interest in Marconi and his invention, and naval communications duly became one of the first major applications of wireless telegraphy. By late 1901, Marconi had even managed to set up a transatlantic radio link between Poldhu in Cornwall and St John’s in Newfoundland. By the following year he was able to demonstrate ‘ship to shore’ radio contact over a range of about 1,000 miles (Roscoe et al., 2013), and the pace of advance was such that in January 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt and King Edward VII were able to exchange greetings sent between Wellfleet in Massachusetts and Poldhu in Cornwall (Roscoe et al., 2013).

By the time of World War I, valve based radio sets were being used in the trenches; in the peacetime between the wars most households had access to a radio receiver for news and entertainment; during World War II, portable radios were being used by agents of the SOE and the Resistance, and ‘walkie-talkie’ radios were being carried on the battlefield; in the 1950s people were watching television in their own homes; in the 1960s they were carrying transistor radios; by the 1970s they were watching colour television; the 1980s saw the mobile telephone networks roll out; in the 1990s we started sending text messages; in the 2000s we connected our telephones and personal computers to the internet by Wi-Fi, and so it seems to go on.

So far we have mentioned only the technological developments that have spun out from the discovery of electromagnetic waves, but it cannot go unsaid that their theoretical and practical benefits to science have been of just as great importance. Another discovery, this time by the American scientists Albert Michelson and Edward Morley (first in 1887) had shown that the speed of light in air does not depend on either the speed of the object that emits the light or the speed of the object that receives it. No matter how the experiment was repeated, or by whom, the result was always the same. Given that it was now pretty well established that light was an electromagnetic wave, this kind of behaviour was contrary to any other known type of wave. Not only that, it defied the sort of logic that scientists had been so comfortable with since the time of the great Sir Isaac Newton. There were also some theoretical problems with the forces between moving electrical charges, for it appeared that they could depart from Newton’s laws. For over a decade scientists tussled with these uncomfortable ‘electrodynamical’ issues, until at last Albert Einstein provided an incontrovertible answer in his revolutionary paper of 1905. The clue is in the title; he did not call it, as he might have done, ‘On the Theory of Special Relativity’, rather he called it ‘On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies’. Relying heavily on Maxwell’s equations, he put forward a radically different view of the world from Newton’s. Difficult though it was to ‘get one’s head around’, once special relativity was accepted it led to a whole new era of scientific thinking, the consequences of which made Einstein a household name. Einstein never forgot his debt of gratitude to James Clerk Maxwell, saying of him[5] that his discoveries were:

‘… the most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton.

And declaring not only:

One scientific epoch ended and another began with James Clerk Maxwell.

but also:

I stood on the shoulders of Maxwell.

Coming from someone like Einstein himself, it is hard to doubt Maxwell’s place in the history of scientific progress.

Through this seemingly never-ending evolution of scientific ideas and technology, electromagnetic waves have shrunk our world to the extent that we may now instantly know what is going on in any part of it; it is up to us, the people who benefit from it all, to see that this evolution leads to things that are for the better rather than the worse. What James Clerk Maxwell achieved, however, was not undertaken with the idea of bringing any immediate benefit. All one can say is that knowledge may be used for the general good, and at some stage knowledge that was originally pursued out of mere curiosity may be exploited to provide tangible benefits. As the theory of electromagnetic waves has clearly shown, the eventual benefit to mankind can be beyond the wildest dreams of the original discoverer. James Clerk Maxwell’s great achievement was that he made all of this possible. How he did so lies at the heart of what physics is all about. For people such as him, lack of knowledge is no barrier, only an incentive.

A17.4 The Birth Dates of George and Dorothea’s Children

The year of birth for Sir John Clerk, 5th Baronet of Penicuik, is given in some places as being 1736, but without firm evidence. His parents, George and Dorothea Clerk Maxwell, married irregularly in 1735, when George was only nineteen years old and Dorothea was not quite fifteen. The Baron, George’s father, accepted the marriage but said that they were too young to live together, and sent George off to university in Leiden to finish his studies. He did not return until 1737. An obvious and significant question is therefore raised about the birthdate of the eldest child, could it be 1736, or would it have been 1738 or later? The following analysis gives a fairly conclusive answer, and also provides the dates of birth of the others, one of whom, whom we identify as James, does not even have a name against his birth record. As James Clerk HEICS, he is an important link to James Clerk Maxwell, for he was his paternal grandfather. We know the eldest son was John, but this would not of itself rule out an earlier daughter. Mackay (1989) suggested that the first-born was a daughter, Agnes, but as we shall see, this must be ruled out. Secondly, as we know, the Baron informs us (Chapter 8) that after George and Dorothea’s early marriage in July 1735 ‘his Wife and he being too young to live together, I sent him to Holand in January 1736’, following which George did not return home until about July 1737 (BJC, p. 146). If the marriage had been consummated after their wedding but prior to George’s departure, any child that resulted would have been born between April and October 1736, after which no further birthdates would be possible before April 1738. Indeed, a daughter Janet was born, at Penicuik, on 7 July 1738.[6]

The next known record is for another daughter Agnes, born in September 1739,[7] which ties in with Mackay, except that he is clearly wrong in stating that she was the first-born. The next child was Joan, baptised on 16 March 1741,[8] which rules out, in all reasonable certainty, any other birth intervening[9] between her and Agnes. It is likely that it was Joan who died the following November because a Janet, an Agnes and a Dorothea all survived to marry. Thereafter, a son was born in November 1742[10] and once again, by the dates, there is very little chance of any other child being born in between. While we do not know the name of this child, we can say that if there was no surviving issue in 1736, he would have had to have been the recognised first-born son, John. However, there is a mention in the Baron’s memoirs (BJC, p. 204) that when John had the measles in about May 1746, he was at Penicuik, whereas at this time George’s other children were at Dumfries (and one of them, William, died as a result of being inoculated against smallpox). The implication is that in 1746 John was away from the other children because he was old enough to be away at school, as was the custom for the sons of gentlemen. John therefore could not have been the son born in November 1742, for he would have been too young. He was consequently born by 1736, while the son born in 1742 was the second son, who was named George.

A third son named William was born at Dumfries and baptised on 14 June 1744,[11] and it is clear that he must have been the poor little fellow who died in 1746. There is evidence that a fourth son was baptised on 20 September 1745,[12] for although his first name does not appear in the transcribed record, the father is given as George ‘Clark’ (as is common in the transcription of such records) and the parish as Dumfries. This would fit in with the birth of James, later James Clerk HEICS, who is given by Foster (1884) as being the third surviving son, and once again we can be sure that no child has been missed from the sequence. Given that the Jacobite rising had been declared the month before and the rebels were already at Edinburgh, one can understand that naming a child James just at that very time could have been seen as an act of overt support for the Jacobite cause. Notwithstanding that the boy would actually have been named after his grandfather, Sir James Inglis of Cramond, fear of negative consequences could have been reason enough for not giving his name on the public record.

The last birth we have a date for is that of a fourth daughter, Dorothea, baptised on 27 February 1747.[13] The sons William, a second of that name, and Robert, are not recorded, possibly due to the family having by then moved to Edinburgh where such missing records are relatively common, especially in the Clerk family.

A17.5 Some Notable Scots of the Age of Enlightenment

- Robert Adam, architect

- William Aikman, artist

- Joseph Black, chemist and discoverer of carbon dioxide and latent heat

- James Boswell, diarist and biographer of Dr Johnson

- Sir David Brewster, chemist and optical pioneer

- Robert Brown, botanist and discoverer of Brownian motion

- James Burnet, Lord Monboddo, pioneer of linguistics

- Robert Burns, renowned poet

- Thomas Cochran, admiral and founder of several foreign navies

- Thomas Carlyle, philosopher and historian

- James Craig, the designer of the New Town of Edinburgh

- William Cullen, physician

- Robert Fergusson, poet

- James Gregory, physician

- Gavin Hamilton, artist and neo-classicist

- David Hume, philosopher

- John Hunter, surgeon

- William Hunter (brother of John), anatomist

- James Hutton, pioneering geologist

- John Macadam, engineer and road builder

- Charles Macintosh, chemist and inventor of waterproof fabric

- Henry Mackenzie, author of Man of Feeling

- James Macpherson, poet and creator of the Ossian legend

- Colin Maclaurin, mathematician

- Alexander Monro I, surgeon

- Roderick Murchison, pioneering geologist

- William Nicol, geologist and inventor of the Nicol prism

- John Playfair, mathematician

- William Playfair (brother of John), pioneering statistician

- Sir Henry Raeburn, artist

- Allan Ramsay senior, poet

- Allan Ramsay junior, artist

- John Rennie, civil engineer

- Sir Walter Scott, novelist

- William Smellie, editor and publisher

- Adam Smith, moral philosopher and economic theorist

- Tobias Smollett, novelist

- Robert Stevenson, lighthouse builder

- James Stirling, mathematician

- Rev. Robert Stirling, inventor of the Stirling engine

- William Symington, steam engine pioneer

- Thomas Telford, civil engineer

- James Watt, steam power pioneer

Note: Even if they were not strictly part of the Enlightenment, James Clerk Maxwell and his friend William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, may be regarded as being products of that golden age.

Notes

[1] mainly from C&G, pp. 431‒32

[2] Collected from various online sources

[3] The top ten amd numbers 11‒100 may be found at:

[4] It is often repeated that Maxwell did not forsee any practical application for electromagnetic waves let alone try to discover them. However, in §16.2 we pointed out that Lewis Campbell recalled discussing such things with him. It is true that Maxwell did not begin any quest for the waves and simply moved on, but it seems that did not stop him wondering about such things. While Heinrich Hertz did manage to discover electromagnetic waves, he too thought they had no practical application!

[5] As any internet search will soon show, the quotations that follow are regularly attributed to Einstein. While there seems little doubt as to their veracity, the original sources are not easy to track down as they appear to have been reported, in one form or another, from various lectures and interviews that he gave over the years.

[6] 1 FamilySearch.org, ID=2:186BXG9

[7] NRS: GD18/5396, 24/9/1739

[8] FamilySearch.org, ID=2:1619Q71

[9] NRS: GD18/5396, 11 & 16/11/1741

[10] NRS: GD18/5396, 28/11/1742

[11] FamilySearch.org, ID=2:161B2HC

[12] FamilySearch.org, ID=2:161B78R

[13] FamilySearch.org, ID = 2:161BCT0