Brilliant Lives

by John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

15.1 The Origins of 14 India Street

15.3 The Clerk Maxwells and Glenlair

15.5 Ownership after John Clerk Maxwell

15.7 14 India Street after the Misses Mackenzie

15 James Clerk Maxwell’s Scottish Homes

It has already been revealed that James Clerk Maxwell was born at 14 India Street in Edinburgh’s Second New Town on 13 June 1831. It had been the house his father and mother had lived in after they married, and although they had started living at Nether Corsock on John’s estate some two days’ journey away, they returned to their town house in Edinburgh each winter until James was in his early infancy. In §9.2 we discovered that James’ grandmother had come to live at the newly built house in India Street after having lived for many years just round the corner at 31 Heriot Row. We now complete the story of how and why 14 India Street came into being, and what happened to it after the Clerk Maxwells moved permanently to Nether Corsock and the house there that eventually came to be known as Glenlair.

15.1 The Origins of 14 India Street

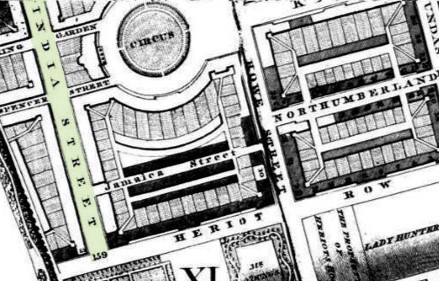

Building in India Street commenced when Heriot Row was more or less finished. In fact, William Wallace,[1] who was responsible for building much of India Street, had started work long before in Heriot Row where he had a building or yard listed at the ‘Back of Heriot Row’ (nowadays called Jamaica Street South Lane), a mews lane from which the stables and other outbuildings belonging to the houses in Heriot Row were accessed. The Kirkwood map of 1817, shows only the outline of the street and the corner house adjoining to Heriot Row, Figure 15.1(a), whereas (Kirkwood, 1819) shows just two houses, built on the west side, Figure 15.1(b). Building work had slowed due to the financial constraints occasioned by the recent Napoleonic wars, but in 1820 James Clerk Maxwell’s father and grandmother were looking for a new house.

Figure 15.1(a) : The Kirkwood map of 1817 shws India Street as it was conceived. It shows only the outline of the street and the corner houses adjoining from Heriot Row.

Figure 15.1(b) : The Kirkwood map of 1819 shows just one new house built on the west side. Whereas the 1817 plan would have eliminated the old route to Stockbridge, here it has been reinstated.

Figure 15.1(c) : Brown’s plan of 1823 shows that by then, not only was India Street complete, so was most of the neighbouring area. There were no more significant changes until the dilapidated tenements in Jamaica Street were demolished and replaced with Jamaica Mews, a low rise housing development.

They were then living at 31 Heriot Row, but it was a large, indeed grand, house and, apart from possibly Mrs Clerk’s stepmother Mrs Irving and some of her stepsisters, there was no other family living there on a permanent basis. The house was in fact owned by Sir George Clerk, John’s older brother whose focus was now on his parliamentary career in London and when he did return to visit his constituency or for the long summer vacation, he had his country seat, Penicuik House not far at all from Edinburgh, as his main residence. But as already suggested in §9.2, the decision to move may have been a family matter: Sir George owned a large house he did not need; his younger brother John lived there but, as John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, he was far from penniless in his own right; Mrs Clerk, their mother, also lived in the house, and she too had some income from an annuity due to her from her marriage contract, and from property. It no doubt occurred to George that he would be better off selling the house and letting his brother buy a more modest property for himself and his mother.

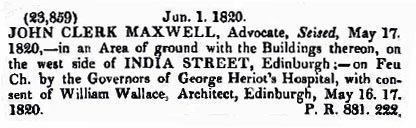

Another part of the equation, however, was that his brother-in-law James Wedderburn was probably looking to move to a bigger house than the one he had in George Street. He and his wife Isabella now had four children and another on the way and, as Solicitor General for Scotland, he was an important man. By May 1820 a decision had been made, and on the seventeenth of that month John Clerk Maxwell got a charter (JCMF, 17/5/1820) from the trustees of Heriot’s Hospital for a house just then being built close to the top of India Street, on the plot allocated for the house that is now number 14 (See Figure 1.2 and Figures 15.1, (a) and (b). As the houses were being built from the top of the street downwards (away from the town), it would have been the closest then available to Heriot Row, in fact just six doors up to the top of the street and then just twelve eastwards to ‘Old 31’, as it was called by the family. A sasine of 1 June 1820[2] records the fact that John Clerk Maxwell had duly obtained his charter and contracted for the house with ‘William Wallace, Architect’, who had acquired the rights to build on the land in question but was in fact more of a builder than architect as such:

By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland

While Kirkwood’s plan of 1819, Figure 15.1(b) shows that building on India Street had only just started, Brown’s plan of 1823, Figure 15.1(c), shows that it was by then substantially complete. It also reveals that the original intention to overbuild the old road running north-west from Edinburgh to Stockbridge was abandoned, leaving the northern terminus of India Street not only a cul-de-sac, but railed off at a height of some 5m above the street below. This means that the north facing ground floor windows of the corner house at the north end of India Street look out onto North West Circus Place from two floors up!

An entry for 14 India Street in the Edinburgh Post Office directory first appears in the year 1821, under ‘Clerk, Mrs.’, while at this time her son is still listed under ‘Maxwell, Clerk esq. advocate, 31. Heriot row’. Until 1826, John Clerk Maxwell continued to give his address as Heriot Row, a clear indication that this was his residence rather than a business address, and Heriot Row is what he gave as his address at the time of his marriage.[3] Not until 1827, the year after his marriage, was John Clerk Maxwell’s name listed at 14 India Street, by which time his mother had been dead for five years.

John never actually moved with his mother to 14 India Street; the notion that John must have lived there because he purchased the house is mere surmise. Certainly, his mother had not purchased 31 Heriot Row, it was actually John’s brother George who had done so (see §9.2n58); living there only occasionally, he had never bothered to list himself at that address. John had been in full possession of his Middlebie estate since reaching his majority in 1811, and from this he drew a reasonable income in rent. The building of the house at India Street may have been his part of the deal to facilitate the sale of 31 Heriot Row to James Wedderburn (see §9.3), and for him it could have represented both an addition to his portfolio of properties and an amenable place for his mother to live nearby, in all likelihood with her step-mother and some of her half-sisters.

That is how it seems to have been. In 1804 John Irving married and left the Irving family home at 5 Buccleuch Place to set up house at 73 Princes Street. In the following year, his brother Alexander Irving also decamped and moved to 27 Heriot Row, and so it is fairly certain that their mother, Mrs Molly Irving, would have accompanied him to keep house, and some of their sisters may have lived with him and some with John. After Isabella’s marriage in 1813, however, it would appear that only Mrs Clerk and John Clerk Maxwell remained at number 31. It seems only natural that some the Irving ladies would then have been lodged with Mrs Clerk, who was just doors away. But when Alexander married in the following year and by 1815 had started a family of his own, it is likely that the majority of the Irving ladies would have been accommodated at number 31. The probable situation, therefore, is that from 1821 the same arrangement would have been continued at 14 India Street.

Even when Mrs Janet Clerk died in March 1822, John Clerk Maxwell did not list himself at 14 India Street, which surely he would have done had he actually been living there. In fact, after James Wedderburn’s untimely death later in the same year, John Clerk Maxwell would have felt inclined to remain close to his sister and his nieces and nephews. Indeed, no-one else was listed at 14 India Street until 1827. The most likely possibility is that Mrs Irving and some of her daughters continued to live there until about 1825, when she re-emerged just a very short distance away at number 38 in the very same street. It cannot be ruled out that Mrs Irving had lived there for some time before choosing to list herself in the directory; alternatively she may have chosen to retire to the family seat at Newton, where in fact some of her daughters were living as late as 1841.[4] Only when we reach the year 1827 can we be certain about the residents of 14 India Street, for it was then occupied by the recently married John Clerk Maxwell and his wife, Frances Cay.

Before we leave this intriguing question, however, let us recall Lewis Campbell’s apparent mistake in saying that ‘Mrs Clerk died there in the spring of 1824’, when in fact we have found definitive evidence that she actually died on 25 March 1822. If the elderly person still living at 14 India Street was Mrs Irving she may well have been mistaken for Mrs Clerk. Had Mrs Irving left there in the spring of 1824, this would clearly tie up with her listing at the number 38 having appeared at the following Whitsun, 1825. It may simply be a case of mistaken identity some sixty years after the fact on the part of Campbell’s informant.

| Clerk, Mary Lady of Pennycuik, 100. Prince st. Clerk, Mrs 14. India street . . . Maxwell, Clerk esq. advocate, 31. Heriot row | The 1821 EPD entries for Lady Clerk of Pennycuik,[5] Mrs Clerk (previously of ‘ditto’) and John Clerk Maxwell, advocate. |

| Following Mrs Clerk’s death, no-one is listed at 14 India Street until 1825‒26, when Mr John Aytoun of Inchdairnie was listed as being the occupier (Pigot, 1825). | |

| [Irving] Mrs of Newton, 38 India street . . . [Maxwell] John Clerk esq. advocate, 31. Heriot row | The 1825 EPD entries for Mrs Clerk’s stepmother, Molly Chancellor, otherwise Mrs Irving of Newton, and John Clerk Maxwell, who was not listed at 14 India street until 1827. |

15.2 The House

We now turn our attention to the house itself.[6] Like all the even -numbered houses, number 14 lies on the west side of the street (Colour Plate 1). Built in 1820 and occupied by 1821, it is of the same Georgian neo-classical style as all the other houses in the upper part of the street, which slopes fairly steeply to the north, intersecting firstly with Circus Gardens on the right and then Gloucester Place on the left, before coming to an abrupt end at North West Circus Place below, the only direct access to which is via a steep flight of stairs.

The street itself, like many others in the New Town, is cobbled with hard-wearing causey stones, with the pavements about two feet higher, so that beyond the kerb there is a sloping skirt of cobbles that leads down to the gutter channel, hewn out of the same hard stone as the causeys. The New Town pavements were originally made of Caithness stone, dressed flat and square, and while some of these pavements remain, in the vicinity of 14 India Street they have been replaced by utility concrete paving slabs that are hardly so attractive. Near each house there is a lighting step that projects beyond the kerb; though redundant now, they allowed people to get in or out of their carriages easily, and without stepping into the probably very dirty street. Given the ladies’ fashions of the time, and the torrents that can flow down the gutters after heavy rain, it was just as well.

By 1820, gas lighting had come to Edinburgh and by 1826 most of the New Town was equipped with it (Shakhmatova, 2012). The original gas lamp, though now electrified, still stands in front of number 14. The house itself is on four levels. Built on the original ground level, there is a basement, with doors to both the back and front, which housed the kitchen and domestic staff. The rear door gives access to the garden, which would have been used as a drying green. The garden, also at more or less the original ground level, stretches westward to a small building that was once the coach house and stable. It now comprises a mews flat above, and a garage below, both of which face onto Gloucester Lane. The front door of the basement opens onto a paved ‘area’ with several storage cellars built under the pavement level. A staircase on the north side of this area allowed servants and tradesmen access to the street outside, while its south side shelters under a sort of bridge formed with massive stone slabs that, after a few steps up, leads from the pavement to the main front door of the house. Here an ancient and faded brass plate advises callers not to ring the pull-bell ‘unless an answer is expected’; but why else would one ring?

Despite its degree of elevation above the level of the street in front and the garden to the rear, we will refer to the floor entered from the main door as the ground floor, and in keeping with British usage the floor above that is the first floor and so on. This is mere nomenclature, for the first floor, with the ground floor and basement beneath, is the third level of the house! After a spacious entrance hall with its high ceiling decorated with a large stucco oval moulding, two ionic columns form an entrance to a lofty stairwell, off which are the doors to the rooms ahead and to the right; while to the far left a wide, carpeted open stairway hugs the walls on its way up to the first and second floors. This stairway is illuminated by an oval glazed cupola in the ceiling that admits a good deal of daylight, but at a price; the grandness and airiness of the stairway requires it to be both high and wide, so that it takes up a space that could have been devoted to three additional rooms.

The high-ceilinged ground floor rooms comprised the dining room (now the exhibition room) to the front and a small office to the rear, the former looking out on the street and the latter over the garden. While the dining room is visible from the street, its elevation above street level, and its distance back from the pavement, gave the occupants relative privacy, and at night time, when the rooms were lit, panelled wooden shutters, which are in use to this day, could be folded out to keep warmth in and prying eyes out. An unusual feature of rooms to this design is that the wall facing the window is cylindrically curved so that the entrance door and the matching ‘press’ door on the opposite side of the room are likewise curved, which looks handsome but must have been costly to make. On the north wall of both rooms are marble fireplaces, with the one in the dining room being large and, although handsome, not ostentatious.

The two main rooms on the first floor are the drawing rooms. They are as large and as high-ceilinged as the rooms below; they also have grand white marble fireplaces, in particular the front room. The front drawing room is the entire width of the house and may be entered either from the landing on the central stairway or from the adjoining rear drawing room, to which it is connected by a wide double door which may be swung wide open so that both rooms can be used as a single, large, L-shaped area. One can imagine a party taking place in which the carpet would be rolled up for dancing in the large drawing room, with space for the musicians and for people to sit out in the other. The rear room has a window that reaches from floor to ceiling, where one can step out onto a cast iron balcony, such as those that can also be seen on the front of some of the houses in the street.

The rooms on the upper floor are somewhat smaller and would have provided, say, three bedrooms, a dressing room, a nursery and perhaps a water closet, but the attic space above was never converted for additional accommodation. One quirky feature of the upper floor is that of the three window spaces to the front, only those on the right and left are glazed, and the central one is merely a dummy. Formed by recessing the ashlars to look like a window space, it allowed two similar sized rooms to the front of the house without unduly affecting the fairly regular frontage of the street. Not only that, it saved on window tax!

For internal lighting, many such houses would have used oil-lamps supplemented by candles, but it was not long before gaslight, already used for street lighting, came inside. According to MacIvor (1978), however, no gas at all was used at 14 India Street until the twentieth century. He attributes the fairly unspoiled original nature of the house to the fact that, as it was rented out until 1891, there was no resident owner hankering to make significant alterations, and little incentive for the landlord to do so either. The occupants were mostly elderly, and so keeping the status quo probably suited them.

The houses were not always provided with some of today’s essential requisites when they were first built and as already mentioned some of the main access roads, such as Howe Street, were not properly built up. Such problems also caused delays in getting a connection to the common sewers and town water supply. Even some of the earlier houses in the Second New Town did not have provision for an inside water pipe or water closets; water was originally brought in to the First New Town houses by a daily army of water caddies (Youngson, 1966, p. 241) Perhaps, after centuries of being accustomed to the circumstances of the Old Town where water was fetched from communal wells and waste was despatched from any convenient window directly into the street, the early designers and inhabitants of the houses in the New Town were slow to catch on, but the truth is that the houses simply advanced much faster than did innovations in plumbing. But according to Rodger (2004, p. 65), even if there were cases of delay in getting connected up, by 1809 most New Town houses were being built with at least basic sanitation and a water supply. We may assume, therefore, that as far as 14 India Street is concerned, they were there from the start.

As to the water supply for the house, it seems that a spur taken from the main supply pipe in India Street fed a cistern in one of the outside cellars off the front basement area. From there, the water would generally be fetched and carried to wherever it was needed within the house itself. Nevertheless, there had also been a pump, the purpose of which is not clear, but perhaps it was used later on to pump water into a cistern within the house itself. While there were likely to have been water closets, for example, located where the present toilets are on the ground and first floors, they could not originally have been flushed by a self-filling cistern for there was no internal water supply; they would generally have been flushed manually from a jug of water kept at hand and replenished by the servants. Some houses collected rainwater from the roof for the purpose, but whether this made any difference to the method of flushing is not known; at least it would have provided the possibility of fitting one of the early forms of flush toilet that was then becoming available.

A fairly minor feature of these houses, but which was nevertheless of great interest to James Clerk Maxwell, was the system of call bells (still in the basement) used for summoning the servants. The brass bells themselves hung where servants could both hear and see them, and after a bell was rung they would have had to watch for which one was still bouncing on its spring in order to be able to tell from which room it was rung. The mechanism was a system of wires, cranks and pulleys that ran from each bell-pull down to the basement, usually hidden within channels in the walls. Lewis Campbell refers to the story of the very young James being fascinated by the bells at Glenlair (C&G, p. 27) and if, as we suspect, he last lived at 14 India Street when he was just about two years old, it is highly likely that, as an inquisitive and active toddler, his early fascination with them first came to light there.

15.3 The Clerk Maxwells and Glenlair

To briefly recap, when in 1809 John Clerk Maxwell came to 31 Heriot Row he was a young man of eighteen or nineteen. Frances Cay was then about seventeen and lived with her family just a block away at 11 Heriot Row. Nevertheless, it was Frances’ elder brother John who first knew John Clerk Maxwell (see §14.4) and their friendship continued for many years before any prospects of marriage arose between John and Frances; perhaps John had some other prospect in mind before he set his heart on Frances, but at any rate they would have known each other for some considerable time before they were married on 4 October 1826 in Frances’ own church, St John’s Chapel, Edinburgh:[7]

| 4. In St John’s Chapel, Edinburgh, John Clerk Maxwell, Esq. of Middlebie, advocate, to Frances, eldest daughter of the late Robert Hodshon Cay, Esq. Judge of the High Court of Admiralty in Scotland. | According to this notice in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine for June-December 1826, John and Frances Clerk Maxwell’s wedding took place at St. Johns Chapel, on the corner of Lothian Road and Princes Street, on 4 October 1826. |

It seems that it did not take long before Frances suggested that John should try to do something with part of the Middlebie estate that he had inherited from his grandmother, Dorothea Clerk Maxwell . While it did bring him an income, he had as yet no house on it that he could call a country seat; the project would be a considerable challenge, but they were game for it:

The pair soon conceived a wish to reside upon their estate, and began to form plans for doing so; and they may be said to have lived thenceforth as if it and they were made for one another. (C&G, pp. 4-5)

And so it was decided that they might live at Nether Corsock,[8] which was then a piece of farmland in need of improvement and with nothing more than a few buildings on it. What it was that turned their attention to this particular portion of land can only be guessed at. It may have been that Nether Corsock had already become their place for the customary summer vacation, or perhaps the lease was due for renewal, or it offered some potential for development; or its situation was particularly appealing; or, even more likely, any combination of such things. Their idea of moving there to embrace an agricultural life tends to corroborate the idea that John was not going to be a great advocate, he was merely:

… doing such moderate business as fell in his way, and dabbling between-whiles in scientific experiment. (ibid.)

When the couple were staying at 14 India Street during the winter of 1830, John received a telling letter from his uncle, John Irving WS, informing him:[9]

There is a case of Mr Stirlings in 2d Decr tomorrow. I have feed by my brother’s advice Mr Archd Bell to attend to it, as you and [he] may be concerned in some other cases of Mr Stirlings you might attend also although I am sorry I cannot fee two counsels. [My emphasis]

John Clerk Maxwell was clearly still taking the opportunity to practise at the bar when he and Frances were overwintering in Edinburgh, but the wording of this passage seems to have been carefully chosen to avoid embarrassment by letting him down gently, for he was not the first choice of counsel, nor was it worth feeing him as a second. John Irving tactfully insinuates that the recommendation of Mr Bell as counsel was not his, but his brother’s. Since Alexander Irving was by then the judge Lord Newton, his recommendation could not be disregarded. By way of consolation, however, he reminds John that he and Frances have not yet let him know when they can come and dine with him. (John Irving was by then a widower).

Like his grandfather George, it turns out John Clerk Maxwell was a practical man, but in place of his grandfather’s impetuousness he came to decisions slowly and carefully, and had a talent for managing things well, and in much detail:

In matters however seemingly trivial – nothing that had to be done was trivial to him – he considered not what was usual, but what was best for his purpose. In the humorous language which he loved to use, he declared in favour of doing things with judiciosity. One who knew him well describes him as always balancing one thing with another exercising his reason about every matter, great or small. (C&G, p. 8)

He therefore must have been far from being the kind of dyed-in-the wool, cut and thrust advocate that his cousin once removed, Lord Eldin, had been. Not only did John Clerk Maxwell have a tendency to reason slowly and deliberately, he inclined in an altogether different direction from the minutiae of the law; he was more interested in the very latest things in science, manufacturing and machinery (C&G, pp. 7−8).

While most of the landed gentry had both a town house and a country estate, Nether Corsock was inconveniently far away from Edinburgh, more or less two days distant, and as we know, it did not then boast a dwelling house befitting a country laird and his family. Thus, a project was formed that John could throw his heart into; In 1830 he started building a decent, practical house. Albeit a far cry from the refinement of Heriot Row and India Street, it was to his own design. Once they had settled into the house that for the time being they called Nether Corsock, the journey back to Edinburgh would be contemplated only when it was strictly necessary, for example, the winter vacation in Edinburgh, and matters of business or social necessity. The railways were yet to come to this area and travel by horse and carriage was a great inconvenience. At least there was a new road, built by Telford in 1824, from Dumfries to Glasgow, which would get them as far as present-day Abington, but according to Lewis Campbell the journey was still grim indeed.

During 1828 and 1829, John Clerk Maxwell did not list himself at 14 India Street in Edinburgh. All the same, the house remained his, and while no-one else listed themselves there, it is not to say that it remained empty; that we simply cannot tell. In the December of 1829, however, the Clerk Maxwells lost their first child, a girl called Elizabeth who died at just one day old. It may be inferred that the child was born in Edinburgh for she is buried in Restalrig Cemetery, just to the east of the city, in the tomb of John Cay (Grant, 1908). At any rate, when they realised that Frances was once again pregnant, they were very probably already back in Edinburgh, for John had relisted his name at 14 India Street for the year 1830, and continued to do so until 1833.

In view of the unhappy outcome of Frances’ first pregnancy, the couple would have been keen to minimise the risks. Frances therefore remained in Edinburgh while John made the journey to Nether Corsock as and when he needed to collect rents or progress the building work. In fact, he placed a time-capsule containing plans of the house and other mementoes, under the floor on 25 March 1831, celebrating the laying of the foundations just eleven weeks before James was born.

In between times, when they were in Edinburgh, the community of tenant farmers, servants and other workers on the estate[10] would carry on just as their laird would have expected them to, irrespective of his absence. By the same token, while they were both at Nether Corsock there would have been someone keeping an eye on 14 India Street. Exactly how the couple apportioned their time between their country and town residences is uncertain, but from 1834 onwards 14 India Street was rented out and ‘Old 31’ became the stopping -off point in Edinburgh on any future visit or vacation.

| [Maxwell] John Cl. esq. of Middlebie, adv. 14 India st | John Clerk Maxwell’s first entry at 14 India Street in the PO Directories. It was for 1827. |

| The house went unlisted from 1828 until the Clerk Maxwell’s returned in 1830. | |

| [Maxwell] John Cl. esq. of Middlebie, adv. 14 India st | The last entry, in 1833 |

After Nether Corsock became the Clerk Maxwells’ main residence, two major events were the death in 1839 of James’ mother, Frances, and John Clerk Maxwell’s purchase of the adjacent Glenlair estate, the name of which he chose to adopt for his enlarged property. Otherwise things carried on much as before, even when Glenlair passed to James. As we have heard, James built a new wing to the family house and a bridge over the River Urr to make it more accessible. Although physics was his main occupation even when he was at Glenlair, he too carried on the life of a country gentleman, dealing with the tenants and collecting the rents on his farms and the other Dumrieshire properties that comprised the still substantial remains of Middlebie. And that is how things stood in 1879 when, on James’ death, the property passed as required by the Middlebie entail to his successor, Andrew Wedderburn, only surviving son of his aunt Isabella from ‘Old 31’.

15.4 Rented Out

After James was safely brought into the world, the family used 14 India Street as their Edinburgh winter residence until the spring of 1834. Lewis Campbell does not say exactly when they gave up living there, and John Clerk Maxwell’s diaries, to which he often refers, seem to have been lost after Campbell’s biography was written.[11] The first mention of them being settled back at Glenlair comes in April 1834 when James had reached the age of two years and ten months (C&G, p. 26). Also, in the following month, we find 14 India Street listed in the Edinburgh directory under the name of John McFarlan, Surgeon, and thenceforward there is no further reference to John Clerk Maxwell or to his son James ever again living there.

The Register of Sasines for Edinburgh shows that John Clerk Maxwell did not sell the property, and the Edinburgh directories for the ensuing years show that he must have rented it to several different tenants. Of course, they would all have had to be of the requisite social standing, and gauged able to pay the rent on time and to keep up the strictest moral standards (or at least a good appearance of it). They included such people as John McFarlan, Colonel and Mrs Thomas Wardlaw, and a Mrs Simson and her daughters.[12]

15.5 Ownership after John Clerk Maxwell

We will now address the question of who actually owned 14 India Street until it eventually passed out of the hands of James Clerk Maxwell’s heirs in 1891. The Register of Sasines reveals what became of the house after John Clerk Maxwell’s death. In June 1856 we find the entry to be just as we would have expected:

JAMES CLERK MAXWELL of Middlebie, as heir to John Clerk Maxwell, Advocate, his father, Seised,- in an Area or Piece of ground with the Buildings thereon, on the west side of INDIA STREET, Edinburgh. By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland[13]

When James Clerk Maxwell was in his forty-third year and presumably thinking about securing the financial future of his wife in the event of his predeceasing her, we find this disposition of 14 India Street in her favour:

Disp. by JAMES CLERK MAXWELL of Middlebie, to Katherine Mary Dewar or Clerk Maxwell, his wife, exclusive of his rights … with the Buildings thereon, on the west side of INDIA STREET, Edinburgh Dated Dec. 26, 1873. By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland[14]

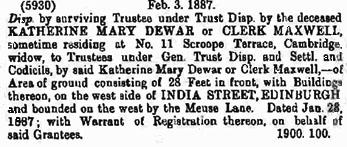

Given the date on which he disponed the property to Katherine, had it been a Christmas gift? Although this predates any warning that James may have had of the symptoms of his final illness, and no other life-threating illness had loomed since 1865, life expectancy then was not great (the mid-forties seems to have been not infrequent). In 1879, shortly after James’ death and when his will would have been under settlement, a notary instrument in which Katherine apparently put 14 India Street in the hands of a trust presumably because she wished such affairs to be managed on her behalf by trustees:

By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland

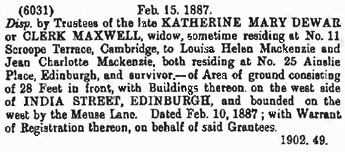

Finally in 1887, following Katherine’s death on 12 December 1886, the surviving trustee disponed the property, presumably for the purposed executing her will:

By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland

This was followed by their ensuing disposition in favour of the heirs:

By Courtesy of Registers of Scotland

The last of these entries therefore tells us what happened next: 14 India Street passed to ‘Louisa Helen Mackenzie and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie, both residing at No. 25 Ainslie Place, Edinburgh’, an address we have previously encountered. But who were Louisa Helen and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie?

15.6 The Mackenzies

But who were the Misses Louisa and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie? To answer that question we must briefly investigate yet another branch of James Clerk Maxwell’s family. We already know that James Clerk Maxwell’s first cousin, Janet Isabella Wedderburn, had married James Hay Mackenzie in 1838.[15] Their son was Colin Mackenzie W.S. (1841‒82), whose has appeared frequently in our story (see §§ 2.2, 2.10 and §9.3) and he would have been the one in line to inherit 14 India Street had he not died just a few years after James.

The main clue given in the record as to the origins of Jean Charlotte and Louisa Helen Mackenzie is their address, 25 Ainslie Place, which cropped up in §9.3 as the residence, from 1861 until their deaths, of James’ aunt, Isabella Wedderburn, his cousin George Wedderburn, and his cousin once removed, Colin Mackenzie. After Colin’s death in 1882, his two sisters Louisa Helen and Jean Charlotte were indeed listed there as ‘Misses Mackenzie’ in the years 1887 and 1897.

The Mackenzies lived at 31 Heriot Row from 1838 to 1841, and indeed Colin was probably born there because he is listed there in the Census of 1841 alongside his parents, at the age of one month (see table in §9.3). By the time the young James Clerk Maxwell arrived to stay with his aunt Isabella, they had moved to a new house called Silverknowe, or Marine Villa[16], near Silverknowes, but they must have remained frequent visitors; they were certainly at 31 Heriot Row to welcome James on his arrival there in November 1841.[17] Indeed, Campbell mentions Colin through one of James’ letters home from ‘Old 31’ written in 1844 (C&G, p. 60) in which he recounted a visit to Marine Villa; James played on the shore with some other boys; Colin, then just three years old, was there as well but went by the baby name ‘Coonie’, which James wrote in Greek letters as ‘kunh’.[18] Much later, when James was laird at Glenlair, Colin became his legal advisor and so in James’ final days he came to Cambridge to be by his side. Campbell (C&G, p. 411) tells us:

… his cousin, Mr. Colin Mackenzie, who acted the part of a brother at the last, as he had done many a time before.

and it was to Colin that he addressed his last words (C&G, p. 416).

Since James and Katherine had no children of their own, James may have considered leaving some of his property to Colin. The estate and the house at Glenlair, being tied in with the Middlebie entail, were ultimately destined for another cousin, Colin’s uncle, Major Andrew Wedderburn, later Wedderburn Maxwell (1821−1896), who had made his career in the Madras Civil Service. His older brothers having predeceased him, Andrew Wedderburn was next in line as heir of entail to Glenlair and Middlebie. Colin would be fully aware of the situation, for he was a Writer to the Signet and not only did he act as James’ solicitor, he was one of his executors. When Colin advised James about those issues he needed to be aware of in drawing up his first will in 1866, he raised the question:

What of the house in India Street? Is Mrs Maxwell or your heir to get that? [19]

James answer was, surprisingly, that the house should not go to his wife; rather, it should go to his heir.[20] But his rationale for that decision may have been that Katherine had never lived in Edinburgh and would have been lonely there. His strategy then was to will her his moveable estate, i.e. household goods, money and so on, and the lease of their current house in London. For whatever reason, he had had a change of mind when he put 14 India St into Katherine’s hands in December 1873.

Notwithstanding that the house was now Katherine’s, any chance of Colin Mackenzie eventually succeeding to 14 India Street perished when he died less than three years after James, at which time Katherine was still alive. His demise is mentioned by Lewis Campbell when finishing the foreword of his book in August 1882:

While the last sheets were being revised for the press the sad news arrived that Maxwell’s first cousin, Mr. Colin Mackenzie, had died on board the Bo[th]nia,[21] on his way home from America. There was no one whose kind encouragement had more stimulated the preparation of this volume, or whose pleasure in it would have been a more welcome reward. August 1882. (C&G, p. x)

At his own request, Colin was buried beside his uncle, George Wedderburn, in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery. George had died of consumption in 1865 (see §9.3). Interestingly, the Blackburns (that is to say, the in-laws of Jemima and Jean Wedderburn), who were also related to the Wedderburns from two generations previous, chose not to attend Colin’s funeral. According to Fairley (1988, p. 77) there had been ‘some whiff of scandal’ about it. Neither Colin nor George had ever married, and they had been frequent companions. When George was diagnosed with consumption in 1860, he was told by his doctors to take a long holiday in a dry climate. He therefore went on a visit to Egypt taking not only his mother with him but also Colin Mackenzie, then about the age of twenty Fairley (1988, p. 162). It is not possible to apply today’s attitudes to the situation, because platonic relationships between men, and between women, were then seen as being quite regular.[22] Nevertheless, in the Victorian era it would only have taken even the vaguest hint, true or untrue, that things were not quite as they should be to bring a swift condemnation. Fairley seems to be suggesting that the Blackburns had indeed caught such a whiff.

Returning now to the inheritors of 14 India Street, as we have seen Katherine’s executors determined that Colin’s two surviving sisters, Jean Charlotte and Louisa would succeed to 14 India Street, an address they never cared to live at. Instead, they stayed on where they were and simply collected the rent. The two sisters were easily traced as it appears they had been living at 25 Ainslie Place with Colin and continued on there after has death, listed as the ‘Misses Mackenzie’ until 1898.[23] The house is unlisted in 1883, the year after Colin’s death, but thereafter, from 1884 until 1898, his sisters are again listed there as ‘Misses Mackenzie’. In 1898, the house was again unlisted, implying the sisters had moved somewhere else. But no fresh entries for ‘Misses Mackenzie’ appear at any other address, and instead we have a ‘Miss Mackenzie’ appearing for the first time at 2 Royal Circus,[24] not far from Ainslie Place. It could be that Louisa Helen had died in 1897 or 1898, In the meantime, Misses Anne and Mary Simson continued renting 14 India Street until 1891, when they bought it from the Misses Mackenzie sisters.

Dying February 1926, Jean Charlotte, shared her brother’s headstone in the Dean Cemetery. Curiously, there is no mention of Louisa. there. All we know about Louisa is that she was born at 31 Heriot Row about 1838, never married, lived in later life with her sister at 25 Ainslie Place, and possibly died around 1897‒8. If she was buried beside her sister and brother, it is strange that it was not recorded on the headstone, and so she was probably buried elsewhere. Their parents, James Hay Mackenzie and Janet Isabella Mackenzie are buried at St Cuthbert’s and St John’s cemetery, little more than a mile away, but Louisa is not mentioned there either.

On the left, the simple monument to Colin and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery. They were first cousins, once removed, of James Clerk Maxwell. Their parents were (Janet) Isabella Wedderburn and James Hay Mackenzie of Silverknowe. On the right, the monument of their uncle, George Wedderburn, first cousin of James Clerk Maxwell. In his choice of burial place and identical monument, Colin clearly affirmed the kinship between him his uncle. The inscriptions say little more than :

Colin Mackenzie WS, 22/4/1841 – 15/7/1882

Jean Charlotte Mackenzie, 23/4/1852 – 2/2/1926

George Wedderburn WS, 25/3/1817 – 1/5/1865

15.7 14 India Street after the Misses Mackenzie

Louisa Helen and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie were the last of James Clerk Maxwell’s family to own 14 India Street, in spite which they continued to live at 25 Ainslie place. In 1891 they sold the house to the incumbent tenants, Mary and Anne Simson. According to the Register of Sasines from then on, the sequence of owners and events at 14 India Street has been as follows, the full details of which are given in the notes: [25]

1891 Misses Mary and Anne Simson, who were already the tenants under the Misses Mackenzie. Anne Simson moved out after the death of her sister in 1914. She may have rented out the house thereafter, but until 1919 the house went unlisted, possibly due to having been used in support of the national war effort.

1919 The judge Lord Robertson became the owner. At some point he converted the stables into a garage and workshop, with a meuse flat above, and had the house wired for electric lighting.

1944 Edward John Keith Q.C., Sheriff Substitute of Stirlingshire, who sold off the meuse flat and later the garage and workshop.

1957 Helen Thompson.

1962 Findhorn Properties Ltd, who altered the house for renting out as separate rooms.

1978 The house was rescued from further depredation by Iain and Marion Macivor, who carefully restored the house to very near its former state (MacIvor, 1978). They also repurchased the garage and workshop to the rear of the house, but the flat above remained in separate hands.

1992 Finally, in commemoration of James Clerk Maxwell, 14 India Street was acquired for preservation by The James Clerk Maxwell Foundation.[26]

Under the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation, the ground floor dining room was made into an exhibition room open to visitors; the study to the rear was turned into a library with books by or concerning James Clerk Maxwell; the first floor drawing rooms were made into a presentation suite accommodating forty people; and finally, the unused rooms on the upper floor, the basement flat, and the garage, are all presently rented out to secure an income to cover the upkeep of the house, with any surplus going to charitable causes associated with the education of young people in science. From 1994 to 2010, the rented out accommodation was home to the International Centre for Mathematical Sciences (ICMS) and in 2021 they returned.

15.8 The Demise of Glenlair

After Andrew Wedderburn succeeded to Glenlair and Middlebie in 1879, he undertook several alterations at Glenlair. He enlarged the rear section of James Clerk Maxwell’s new wing to Glenlair House in order to provide a billiard room and extra bedrooms. As he needed more servants’ quarters, he also added to the external buildings adjoining the house and converted the attic space in the original part of the house built by John Clerk Maxwell. The change in its external appearance of the front elevation was subtle, betrayed by some new dormer windows.

From Andrew Wedderburn Maxwell, Glenlair passed to his son Major James Andrew Colvile Wedderburn-Maxwell in 1896, and from him in 1917 to his son Brigadier John Wedderburn-Maxwell, a soldier who saw service in both World Wars. After the First World War, the estate would not pay its way, but one means of making some money towards its upkeep was to let it out to wealthy businessmen for shooting parties that were in demand for two to three months in the late summer and autumn of each year (Wedderburn-Maxwell, 1985). It was during such a let in 1929 that the excessive heat from an unduly fierce kitchen fire caused a beam in the attic above to catch alight. In such isolated houses, there was no easy way to tackle the blaze without having a suitable emergency appliance immediately on hand, which unfortunately was not the case. When a fire appliance did eventually arrive on the scene, they could not get water[1] and so they were unable to prevent the fire spreading along the roof and into the newer wing. Had there been a heavy door in the connecting passageway, the newer wing might have been saved. As it was, it probably fared worse.

After the fire, the partially gutted 1860−90 wing was left to the elements, while Brigadier Wedderburn-Maxwell was obliged to reclad the roof of the old house in order to provide what he may at first have thought of as temporary living quarters. This suggests that the ground level floor and the internal walls may have been left sufficiently undamaged to leave a basis upon which to build the structure seen in later photographs. Executed in makeshift fashion with corrugated iron and wooden boards, a loftier roof space was formed under a single lengthways ridge.[28] This roof outline was certainly not there in 1928,[29] the year before the fire, as a photograph taken in that year clearly shows. Interestingly, for reasons unknown, in 2014 several US corrugated iron suppliers were referring to the roof of the resurrected Glenlair House in testimony to their product almost as though it had been one of the original design features! [30]

That the owners of Glenlair would live under such conditions seems surprising, but although they had the land, they had no great family fortune. Following the Great War there had been years of economic difficulty in the UK, and in 1929 the world was hit by the great depression, so that any roof over one’s head was better than none.

Given that he had disentailed the estate in 1922, it may be that Brigadier Wedderburn-Maxwell sold Glenlair even before the fire, but there were two main factors against this. The first was the legacy of the Great war, which not only badly depleted the male workforce, especially in the countryside, but also changed social attitudes towards the landed classes to an extent that made running a country estate a burden rather than a benefit. Secondly, as already mentioned, there was a dismal economic climate in which there were far many more prospective sellers than buyers of such properties. He did, however, manage to sell Glenlair Mill (just over six acres) in 1930, but it was not until after the Second World War that the remainder of the estate was sold, to John Liston Dalrymple, on 5 September 1946. In 1949, it was broken up and sold in lots, the last one of which, Glenlair Home Farm comprising some 127 acres, was purchased by the father of the current owner, Captain Duncan Ferguson, in February 1950.

Captain Ferguson, who was brought up at Glenlair, established the Glenlair Trust, which has been responsible for restoring the old house and the vestibule of James Clerk Maxwell’s wing, and it is a work in progress (Glenlair Trust, 2012). He lives in the same gardener’s cottage that John Clerk Maxwell and his wife Frances Cay lived in nearly two centuries ago before John had built their new house that he was to call Glenlair. The Clerk Maxwells made it their home, the home in which the young James Clerk Maxwell was raised between the years of two and ten, and where he came back every summer in the years thereafter. After his father’s death, one of the front rooms on the ground floor [31] became the study in which he worked on many of his papers. From 1865 to 1871, Glenlair was his main residence, during which period he fulfilled his father’s original concept of an additional wing to the house. It was unfortunate that he had no son of his own to benefit from the adventures and freedoms that he himself had enjoyed there as a boy, or from the sort of caring and devoted relationship he had with his own father, the creator of Glenlair.

Notes

[1] William Wallace and his brother Alexander were listed at ‘Back of Heriot Row’ (1820‒22), 44 India St (1823‒4) and 22 India St (1825‒29). Perhaps as they built up properties in the street they kept these particular properties as show-houses, if not actual residences. By 1830 their activities seem to have moved on to St Vincent St (nos. 8 and 10). Wallace is also listed in the Canongate, 10. St John St, which seems to have been more of a permanent base (if it is indeed the same William Wallace).

[2] RS: Register of Sasines, PR 881.222, (23,859), 1/6/1820

[3] SOPR:Marriages, 685/01 0630 0360 Edinburgh, 4/10/1826

[4] When Mrs Molly Irving died in 1828, her unmarried daughters listed themselves in the directory under ‘Irving, Mrs of Newton’ (‘Misses’ was often mistranscribed as ‘Mrs’), and continued to do so until they moved round the corner to Doune Terrace in 1830. In 1831 and 1832, the year of Lord Newton’s death, a single ‘Irving, Miss of Newton’ was listed there, even though there were others then alive.We may therefore surmise they had lived together all along.

[5] At that time, Princes’ Street was referred to as ‘Prince street’ and ‘Prince’s Street’

[6] Since 1967, 14 India Street was registered by Historic Scotland as a Category ‘A’ listed building. Designated as such on the basis of their historical or architectural significance, listed buildings are legally protected from alteration without permission, with the most important examples being accorded Category ‘A’ status. See http://portal.historicenvironment.scot/designation/LB29133 for the particulars. Further information on the house is available from CANMORE: ID 135539, and among their records is a photograph of India Street as it was c. 1950 (see image SC512099 at https://canmore.org.uk/search/image?SIMPLE_KEYWORD=14%20India%20Street ).

[7] Note 3 above and Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (1826)

[8] Nether Corsock was part of the John Clerk Maxwell’s estate in Kirkcudbrightshire, about twelve miles to the west of Dumfries. It was the name of the estate on the Gillon Plan of 1801 (GGD56/1, 1806) at which time it did not include Glenlair, which was to the south of the boundary formed by the Glenlair burn, until its purchase by John Clerk Maxwell in 1839. On Ainlsie’s County map of 1821, the site of the present Glenlair house is marked as Nether Corsock, which is the name by which the Clerk Maxwell’s initially referred to it (though they frequently wrote just Corsock). After the purchase of the Glenlair estate, however, John Clerk Maxwell decided to rename it Glenlair (C&G, p. 25), and by 1850 it is so marked on the 6’ OS map, on which Nether Corsock is now marked as a steading some way to its north and the original steading of Glenlair is now marked as Nether Glenlair, to distinguish it from the new creation. The River Urr, to which James Clerk Maxwell frequently referred, forms where the eastern border of the estate.

[9] DGA: GGD/56 Unsorted Box 1, 1/12/1830

[10] When James Clerk Maxwell was a boy he referred his playmates at Glenlair, who were the sons of these ordinary people, as his ‘vassals’. Although this was part of his play with them, and was not meant in any derogatory fashion, it did reflect the prevailing social realities between laird and minion.

[11] DGA: GGD56/‒ Unsorted Letters, 14-16/6/1898

[12] We surmise that the tenants From 1820 to 1822 were John Clerk Maxwell’s mother, Janet Clerk, together with her step-mother, Mary Irving, and her step-sisters. Mrs Clerk died in 1822 but the others remained until 1824 when they moved further down India Street. From 1825 to 1891, the documented tenants were successively:

- 1825‒26 John Aytoun of Inchdairnie

- 1826‒33 John and Frances Clerk Maxwell

- 1834‒38 John McFarlan, FRCS, Surgeon

- 1839‒42 Robert McIntosh, Esq., writer

- 1843‒44 James Scott, Esq.

- 1844‒63 Lt. Col. Thomas Wardlaw (1787-1863), of the Bengal Native Infantry, promoted to full colonel in 1855.

- 1864‒69 Col. Wardlaw’s widow, Mrs Margaret Wardlaw (1812-1869), who continued to live there until her death in 1869.

- 1868‒71 During Mrs Wardlaw’s last two years, a Mrs Simson was also listed; she carried on there after Mrs Wardlaw’s death in 1869.

- 1871‒91 Mrs Simson having died, a Miss Simson was now listed; presumably one of her daughters.

John McFarlan was attached to the Royal Public Dispensary in West Richmond Street, not far from the University. Founded by Professor Andrew Duncan in 1776, the dispensary was a clinic that trained medical students and provided free medical care to the poor. There is still an Andrew Duncan clinic, but now at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Morningside.

Lt. Col. Thomas Wardlaw was listed in the 1855 London Gazette along with Lt. Col. Hugh Morrison, Lewis Campbell’s stepfather, when they were both posted, for pension purposes, as full colonels. Having been in the very same regiment, Was Lt. Col. Morrieson able to give a recommendation to John Clerk Maxwell that his fellow soldier would make a suitable tenant for 14 India Street? Mrs Wardlaw’s last entry in the directory was posthumous. She and her husband are buried in the Dean Cemetery, which served that part of the New Town and of which we will hear more later on.

Mrs Simson appears to be Mary Shepherd (1794‒1871), who was the widow of Henry Simson, minister of the Chapel of Garioch, Aberdeen (Couper & McIver, 1992). They had two daughters, Anne (1829‒1915) and Mary (1839‒1914). Couper and McIver are wrong in saying that Anne and Mary were their granddaughters, for their only son John Thomas Simson WS died unmarried at the age of only twenty-eight in 1865 (Writers to the Signet, 1890).

[13] RS: Register of Sasines, PR 2057 82 (**6), 17/6/1856

[14] RS: Register of Sasines, 431.188 (13,304), 19/1/1874

[15] She was referred to by the family simply as Isabella. James Hay Mackenzie WS (1809‒1865) was the third surviving son of Colin Mackenzie of Portmore (1770‒1830) and a nephew of Sir William Forbes the banker. He was Deputy-Keeper of the Great Seal, 1858‒65, in which role he was succeeded by his son, Colin, who was James Clerk Maxwell’s cousin and legal adviser. Prior to his marriage to Isabella Wedderburn,, James Hay Mackenzie lived at the Mackenzie family home, 12 Charlotte Square, which was then only recently built. After their marriage, James moved in with Isabella and her mother at 31 Heriot Row, but by 1841 they not only had a town house of their own at 2 Randolph Cliff close to the Dean Bridge, but also a newly built seaside retreat at Silverknowe (no final ‘s’). The location would have made Silverknowe just a four mile walk away. There is, however, a gap of about ten years between 1846‒56 when no town house is listed for James Hay Mackenzie, and so we may presume that during this period they lived permanently at Silverknowe. Sadly, Isabella, who liked plenty of bracing fresh air, which she perhaps felt was beneficial to her health, developed a cough about the winter of 1849‒50 which eventually became persistent (Fairley, 1988, p. 157). This was probably symptomatic of consumption which was then widespread, and having tried to seek a cure at Madiera, she died in 1853 leaving six children, Colin being the eldest son. James remarried Selina Jane Norton but died in 1865 (at least four people in this study died in that same year, but no report of an epidemic has been found). All three are buried side by side in the churchyard of St John’s Episcopal Church off of Lothian Road.

[16] The former Marine Villa, or Silverknowe, built by James Hay Mackenzie for his bride (Janet) Isabella Wedderburn, has an interesting history. What remains of it is now 47 Marine Drive, Edinburgh. It lies within the precincts of a 1950’s development, a golf course, situated in a pocket of what is still fairly open countryside (with sheep!) that lies not far from the New Town, and less than 200m from the shore of the Firth of Forth. Until 1855, James Hay Mackenzie is listed at Silverknowe in the County pages of the Edinburgh P.O directory under the locality of Davidsons Mains, then a small independent village, about three miles from the town centre.

Silverknowe and its neighbouring property, Broomfield, have been superimposed on Gellatly’s map. Many of the areas highlighted in green are still planted with trees but the access roads shown in yellow are reduced to tracks. The village of Cramond is on the coast to the west, while Granton and Leith are to the east while Edinburgh is to the south-east.

Based on Gellatly’s New Map of the country 12 miles round Edinburgh, 1834, reproduced by NLS CC-BY license.

[17] One of Jemima’s watercolours depicts the scene with James and his father arriving with aunt Isabella and cousin Jemima. They have alighted from a coach and are being greeted by the Mackenzies at the front door of ‘Old 31’ (Wedderburn, c. 1841).

[18] This is just one example of his playing with words and codes in his letters home to Glenlair; in the same letter he writes Marine Villa as “murrain vile” and signs off as “JAS. ALEX. McMERKWELL”.

[19] DGA: GGD56/Unsorted Box 1, Letter: Colin Mackenzie to JCM, 1866

[20] James’ will and testament (SWT: James Clerk Maxwell, SC16/41/35, 1879) as originally drawn up in 1866 left Katherine all his movable property and the lease of their house in London. The house at 14 India Street is not specifically mentioned, for he simply intended that it should go to his Aunt Isabella’s eldest surviving son along with all his other heritable property, entailed or otherwise. In July 1873 he added a codecil to his will revoking his share in the Prospect Hill farm in favour of the Cay family, but mentioned nothing else. 1874, however, he had a change of heart regarding Katherine, and simply disponed 14 India Street to her outright. As this required no change to the terms of his will, there is no mention whatsoever of the house. In addition to Katherine and Colin Mackenzie, the other executors were Maxwell’s friend and colleague Prof George Stokes and his physician Dr Paget, both of Cambridge. Colin Mackenzie’s legal practice was very likely to have been Messrs. Mackenzie and Black, W.S., 28 Castle Street, which follows from the fact that Mackenzie and Black were involved in drawing up deeds for James Clerk Maxwell, and it would have been natural to keep such business ‘in the family’, e.g. DGA: GGD/56/UB1, Letter from Colin Mackenzie to James Clerk Maxwell, 2/7/1866 and the Disposition of 1874 on Katherine Dewer’s behalf, (RS: Register of Sasines, 431.188 (13,304), 19/1/1874).

[21] In the second edition of his biography, Campbell orrected the Bosnia to the Bothnia, a Cunard passenger liner that regularly sailed betwen Liverpool and New York. The ship did not sink; Colin died of apoplexy on 15 July 1882 while the ship was within a da’y’s sailing of Liverpool (Fairley, 1988, p. 77) .

[22] In addition, Colin may well have been living at 25 Ainslie Place since early 1865 since his father, James Hay Mackenzie, had died in February some months before George’s death, and he must have had time to place his new address in the forthcoming directory for 1865. Colin appears to have inherited the house or had the liferent of it.

[23] It is also possible that the sisters had continued to live with their stepmother, and so they may not have arrived at Ainslie Place until as late as 1869. That said, it is very likely that at least one of them, perhaps Louisa who was the elder of the two, would have gone to live with him from the outset to act as his housekeeper.

[24] Coincidentally, there was also one at 2 Tait Street, but this is in an artisan quarter where a middle class miss would not be expected to reside.

[25] Expanded details of the chronology of ownership after Louisa Helen and Jean Charlotte Mackenzie are given below:

1891 The Misses Mackenzie sold the property to the incumbent tenants Misses Mary and Anne Simson.

1914 Miss Mary Simson made a codicil to her will in February 1914 and appears to have died later that same month. Miss Anne Simson, now on her own, moved to 13 Torphichen Street, a grand terraced house that still stands despite much local redevelopment. It is in a similar style to 14 India Street, but it is in the much busier and more commercial area of Haymarket. She is listed there from 1915 to 1919 whereas the gravestone inscription given in Couper & McIver (1992) has it that she died in 1915, but this could simply have been a misreading of the last digit of the date. The 14 India Street may have been rented out by Anne Simson during the years 1914-18, but if so no occupant is listed in the Edinburgh directory. The dates suggest the possibility that it could have been used as accommodation or offices in support of the national war effort.

1919 After the war, the house was sold to Thomas Graham Robertson, Advocate who later became the judge Lord Robertson. It was at this time that electricity was first introduced into the house.

1926 A waiver was granted to convert the stables and wash-house in 25 Church Lane (now renamed as Gloucester Lane) to a garage, workshop and house above, and to treat them as separate subjects independent of the house on India Street.

1944 Lord Robertson’s trustees and widow sold the house to Edward John Keith, advocate, formerly of 2 Circus Gardens, just round the corner off the north-east end of India Street.

1951 Edward John Keith QC sold the meuse house above the garage and workshop to Eleanor Emma Bearsley, formerly of 11 Hillview Rd., Corstorphine. The meuse house is therefore no longer part of the main property at 14 India Street.

1957 Sheriff Edward John Keith Q.C., now at 24 Merchiston Park, sold the house to Helen Thompson of 15 Melville St. He was then Sheriff Substitute of Stirlingshire, etc., and in 1960 became Sheriff Substitute of Lothian and Peebles.

1957 Sheriff Keith now sold the workshop and garage on 25 Church Lane to the trustees of the marriage contract of the late George Herbert Liston Foulis, Banker, and Grace Marguerite Liston Foulis, née Carter. Liston Foulis was the youngest son of the 9th Baronet Liston Foulis of Colinton. He was a J.P. and manager of the Royal Bank of Scotland in Edinburgh, and is buried in Colinton churchyard. The transaction was dated June 18th, just 8 days after the death of Mr Liston Foulis.

1959 The garage and workshop were conveyed to Mrs Grace Marguerite Liston Foulis, or Carter, in her own right.

1962 Helen Thomson, or Thompson, having bought the house on its own in 1957, was now living at 15 Howard Place. She consequently sold the house to Mr. Arthur Gray of Findhorn Properties Ltd. and Dorothy Rosamond Carswell, or Gray, of 3 Findhorn Place on the south side of the city. The house was then altered for renting out as separate flats or rooms during Findhorn Properties’ period of ownership.

1967 14 India Street was protected as a Category ‘A’ listed building by Historic Scotland.

1978 Findhorn Properties Ltd sold 14 India Street to Iain Macivor and his wife Marion, formerly of 25 India Street, which is a tenement property near the north-east end of the street. The MacIvors then carefully restored the house to its former state.

1981 The executors of Mrs Grace Marguerite Liston Foulis, 13 Moray Place, sold the rear garage and workshop to William Dickson WS of 6 Belgrave Crescent.

1984 William Dickson WS, having moved to 13 Moray Place, sold the garage and workshop to Iain and Marion Macivor, leaving only the meuse house above the garage and workshop in separate hands. . The Macivors were instrumental in preserving the house and restoring the house to its former condition (MacIvor, 1978)

1992 Iain and Marion Macivor sold 14 India Street to the trustees of the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation who carried on the restoration.

[26] https://www.clerkmaxwellfoundation.org/index.html, registered charity SC015003

[27] Rautio (2006). Despite the proximity of the duck pond, which presumably was low in water that summer.

[28] See http://www.glenlair.org.uk/gallery/glenlair-historical/Glenlair-House-1950.jpg

[29] See http://www.glenlair.org.uk/gallery/glenlair-historical/1928-with-Col-Hannay.jpg

[30] For example, (Winsor Roofing, 2014) informed us:

One of the loveliest historic homes that has corrugated roofing is in Scotland. It is called Glenlair, and was the home of Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell, who developed a lot of things, but the only one this writer can immediately grasp is that he helped develop color photographs. He also had great taste in homes. Although Glenlair is still suffering from the effects of a huge fire in 1929, it and its corrugated roofing are still standing and still beautiful. The grand old house is slowly being restored by private donations.

Many other such websites gave the same information.

[31] Shown as the “business room” in the Newall plans of 1868, CANMORE: ID 212680 available at https://canmore.org.uk/site/212680/glenlair