Brilliant Lives:

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

14 The Cays and the Hodshons

We now come to James Clerk Maxwell’s mother’s side of the family, the Cays. Frances Cay’s parents were Robert Hodshon Cay and Elizabeth Liddell. Robert took his first name from his grandfather, as was the custom, but his middle name came from his mother’s family, the Hodshons of Lintz. The origins of the Cays and the Hodshons were not Scottish, for Robert’s parents were from the north-east of England. We will begin with their rather interesting background and how they came to settle north of the border.

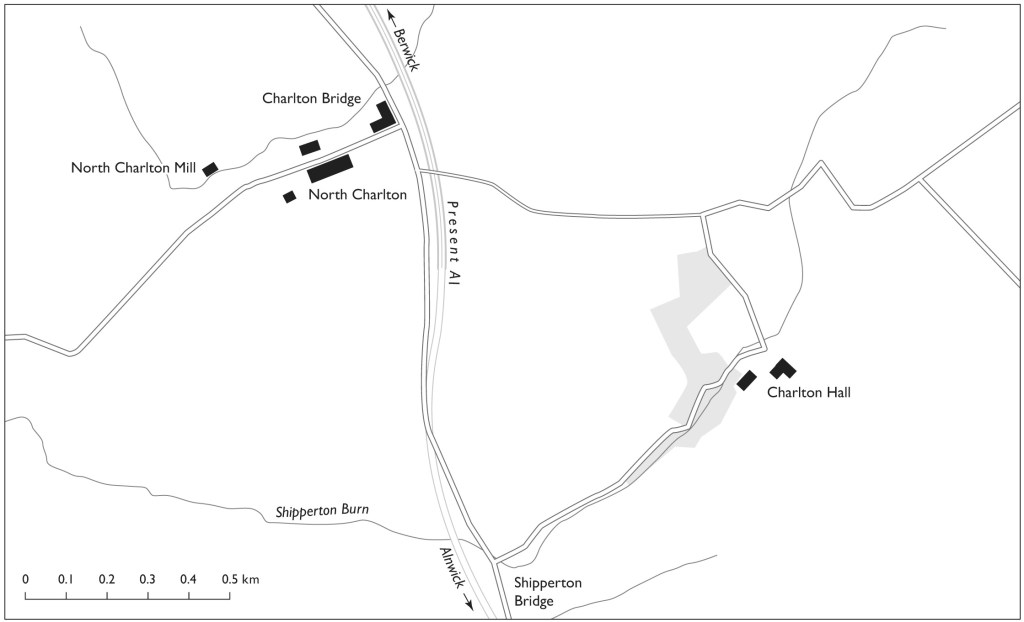

14.1 The Cays of Charlton Hall

Although this family were known as the Cays of Charlton Hall (Burke, 1835−8, pp. 384−5) the association with North Charlton in Northumberland came about only around the end of the seventeenth century. In their earlier days, when the spelling of the name was Kay or Key, they nevertheless seem to have been living in the same general area as North Charlton, in fact near Alnwick, an ancient market town lying just to its south and within thirty miles of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish border (Figure 14.1).[1] They therefore lived on the English side of the Eastern March of the turbulent border region, which until the seventeenth century was effectively under the separate rule of the March Wardens and beyond the direct rule of the separate monarchs of Scotland and England, as discussed in Chapter 6. As with many of the families that lived in these parts, the Keys were drawn into the frequent ructions that took place. Indeed, they settled their scores, as others did, in the time-honoured manner, and so at some early date a duel took place at Alnwick between one of the heads of the local Key family and some adversary now unknown. Key slew his opponent and made off south to Newcastle-upon-Tyne to escape the reach of the March law, according to which he had committed an act of treason. His estate and possessions were subsequently forfeit and so he had to remain in straitened circumstances, sequestered in Newcastle for the rest of his days.

Key’s family stayed on in Newcastle and in subsequent generations they managed to build up a brewing business of significance, which was then in the hands of Thomas Cay, who was a baker and brewer in Newcastle from 1594, the year he was apprenticed, until January 1623, when he died (Bateson, 1895, pp. 297−300; Cay et al., c. 1947). Following Family Tree 7, it may be seen that Thomas married Margaret Totherick, a widow, with whom he had five children, the eldest of which, another Thomas, died before the age of ten. The business therefore passed to his oldest surviving son, the first recorded John Cay, who was born in 1605. When John died, the business was then carried on by his widow, Isabel Wilkinson, until it eventually passed down to their second son, Robert Cay (1634−1682). When this took place is not known, but by the time Robert Cay died, he owned lands in Tynemouth, was a free baker and brewer of Newcastle, and was a prominent non-conformist, most likely a Puritan. his widow, Barbara Carr, whom he had married in 1665, expanded the business and was able greatly to improve the family fortunes. Thereby this lady was able to acquire much property in and around Newcastle and, significantly, to educate her four sons. According to (Cay, et al., c.1947), it was her mother-in-law, Isabel Wilkinson, who did this, but (Burke, 1834, p. 384) seems to be right in saying that it was Barbara Carr, for Isabel appears not to have had the requisite four sons to educate and give houses to. The incidental details given in the family tree indicate that business had already started improving under Barbara’s husband, for he had become a free burgess and acquired property, and it is likely that Barbara carried on the upward trend after Robert’s death in June 1682, by which time her eldest son Jabez, was already at Edinburgh University. Moreover, it was she who had the four sons alluded to as being educated, namely Jabez, John, Robert and Jonathan, and gave them houses. The upward trend was still continuing by June 1682 when her eldest son, Jabez, was at Edinburgh University. Again according to Burke, it was her third son, Robert, who eventually brought the business to ruin and in the aftermath took off to Londonderry to escape the consequences. All of this appears to be consistent with the Cay Family Tree (Cay et al., c. 1947), which notes that it was this Robert who was in partnership with his mother.

This catastrophe with the family business seems to have occurred after 1704, for Barbara’s son Robert was admitted as a free hoastman[2] of Newcastle in that year and therefore had not yet taken flight. Reduced in circumstances[3] but undeterred, the brave widow Barbara started all over again, and once again met with success. She carried on until 1723, in all probability with the help of her grandson Robert Cay, John’s son, who went into the brewing and baking business and was the one who eventually carried it on. But before moving on to his part in the Cay family history, we must go back to the stories of his father John and his three uncles, Jabez, Robert and Jonathan.

Jabez Cay was sent to continue his education at the University in Edinburgh where, in November 1682 (by which time his father was already dead) he was unlucky enough to be expelled for taking part in a student romp that involved burning an effigy of the Pope. While it was the sort of traditional rag that the majority of Edinburgh citizens would have wholeheartedly approved of, this took place under the chancellorship of the Roman Catholic Duke of York, later James VII, who had been appointed as head of the Privy Counsel in Scotland by his brother the King, Charles II.[4] Jabez and his fellow rompers were duly brought before the Privy Council and, with all due severity, banished from Britain. Faced with banishment, Jabez was at least lucky enough to be able to count on his mother’s financial support, and so it was that he took himself to Europe not in poverty, but able to go off to Padua and continue his studies there and eventually qualify as a physician.

Some years later, after James VII’s abandonment of the throne, Jabez was able to return to Newcastle where he married Dorothy Gilpin (1668–1708) she was the sister of William Gilpin of Scaleby Castle (1657−1724), a cleric and antiquarian, who in 1718 became the recorder of Carlisle.[5] Now, here we have a connection to the Clerk family, for William Gilpin was a fellow antiquarian of the Baron, Sir John Clerk 2nd Baronet of Penicuik, who corresponded with him and visited him shortly before he died (§4.9; BJC, pp. 116−119). In the spring of 1724, the Baron set out on a journey to see coal mining at Newcastle, Hadrian’s Wall and antiquities in and around Carlisle (ibid.). It was Scaleby, 5 miles to the northeast of Carlisle, that he visited Mr Gilpin and was impressed with his kindness and enthusiasm in showing him all the local antiquities. Jabez Cay was likewise an antiquarian, and at one time possessed the ancient Roman stone from Benwell to which a curious story is attached.[6] William and Dorothy’s younger brother, John Gilpin (1670−1732), returned the compliment by marrying Jabez’ sister Hannah Cay (b. 1675) in 1699; he later became a wealthy and respected merchant in the Virginia tobacco trade at Whitehaven in Cumberland (Symson, 2002). Through the Gilpin family, Mary Dacre, wife of Sir John Clerk 5th Baronet of Penicuik (see §9.1) was also related to the Cays, for her grandmother was Susannah Gilpin, Dorothy Gilpin’s niece (Family Tree 5).

Jabez Cay, like his mother, prospered at Newcastle and he was able to purchase a moiety (half) of the estate of North Charlton in August 1695, which he managed to accomplish with the assistance of Jonathan Hutchinson MP (c.1662−1711), each simultaneously buying one half of the property (Hayton et al., 2002b; Burke, 1834−38, vol. 1, p. 384). It was in this way that North Charlton came to be long associated with our Cay family.

Note the local placename Shipperton, corresponding to Shepperton, the name Robert Dundas Cay gave the house he built in Edinburgh.

As well as being a keen antiquarian, Jabez was also an avid mineralogist, as revealed by his letters over the period in which he wrote to the London physician and naturalist Martin Lister (1639−1712).[7] However, it was through his interest in antiquities that he became the correspondent and friend of Ralph Thoresby (1658–1725), a merchant in Leeds who later in life spent most of his time on antiquarian studies and kept up a prodigious correspondence with many of the learned men of his time. He also kept a voluminous diary, which, along with his correspondence, has been published (Thoresby, 2009; Colburn and Bentley, 1832). Amongst the diary pages we find:

[15 April 1695] had Dr. [Jabez] Cay’s, of Newcastle, company, viewing collections, &c. with several other friends at dinner; with whom spent most of the afternoon amongst the coins.

[6 Jan. 1702] I heard also that my kind friend, Dr. Cay, of Newcastle, is very weak, if alive.

[8 February 1703] Visited cousin Whitaker, who told me of the death of my kind friend and benefactor to my collection of natural curiosities, Dr. Cay, of Newcastle; sense and seriousness filled his last hours, as Mr. Bradbury’s expression was. He died 22nd January, Lord sanctify all mementos of mortality !

[21 May 1703] … we had the convenience of seeing the Hell-kettles[8] the best account of which, is in my late kind friend Dr. Jabez Cay’s letter, inserted by Dr. Gibson in the new edition of the Britannia [Romana], p. 782.

On Jabez Cay’s death in January 1703, his brother and successor John Cay (1668−c.1730) continued to correspond with Thoresby (as mentioned in the latter’s diary). However, not only did John succeed to Jabez’ moiety of North Charlton, he was subsequently able to take over the whole estate by buying out Hutchinson, which certainly shows that he had significant wealth. In fact, he was able to make a match to a wealthy heiress, Grace Woolfe of Bridlington, Yorkshire. He was perhaps able to live as a gentleman, for there is no note of him actually being involved in the family brewing business, which part seems to have been taken over by his brother Jonathan.

As already mentioned, the first Robert Cay and his wife Barbara had four sons in all. After Jabez and John came Robert, the second Cay of that name, who fled to Northern Ireland, where he started afresh and, with his wife Mary Field, raised two sons, Robert and John, who had property at Burncranagh,[9] approximately 12 miles to the northwest of Londonderry. Although Robert was in partnership with his mother, because he was admitted as a freeman of the Hoastmen of Newcastle he was in fact in the coal trade rather than brewing. It was the fourth son, Jonathan, who went into the family brewing business, for it was he who was the freeman brewer and baker (Cay Family Tree, c. 1995). We know very little more of Jonathan other than, like his older brother Robert, he did not stay in Newcastle, in fact he ended up in Virginia as a preacher.[10] What we do not know was whether this was of his own volition or whether he too fled as a result of the collapse of the family finances.

When Grace Woolfe’s father died c. 1709, he remembered John, his daughter and their family in his will:

I, Henry Woolfe of Lay Yett, near South Shields…

To my Son in Law John Cay & Grace his wife my daughter…

To my Grandson Robert Cay … Messuage [i.e., a dwelling house] & five salt pans held from Dean and Chapter … twentieth part of Elswick Colliery…Farm in Harton lately bought of Thomas Watson.

Dated April 25th, 1709 … Executors, John Cay & Grace his wife. (Phillips, 1894, p. 210)

His grandfather’s bequest made good provision for Robert (1694−1754), who was then but a boy, for he duly became a merchant and salt manufacturer at Laygate (given as Lay Yett in the will) in South Shields, which is on the south bank of the river Tyne and closer to the sea than Newcastle itself. The will also informs us that he was left a share in a coal mine at Elswick, which neighbours Benwell, the origin of the Benwell stone given to his uncle Jabez by Mrs Shafto.

According to family tradition, Robert philanthropically published a letter that appeared in the Newcastle Courant of 5 January 1751 (Enever, 2001; Thomson, 2005) suggesting the institution of an infirmary at Newcastle. However, the only direct evidence for him having been the writer is that it is signed with the initials B. K., and there is an opposing story that it was in fact written by a Newcastle surgeon, Richard Lambert, Two other sources, however, say the writer’s initials were ‘K. B.’ (Mackenzie, 1827; Baillie, 1801, p. 322). Now, the true identity of the philanthropist who suggested the idea was probably unknown even then, for the ward named to commemorate the instigation of the hospital was simply designated as the ‘B. K. Ward’. Robert Cay did have a plausible claim to the initials ‘B. K.’ inasmuch as he may have been known as Bob Key, but on the other hand Lambert, for whom we have no such plausible explanation, had already been an active campaigner for he had written to the Courant about the town’s water supply the previous November (Baillie, 1801, p. 154).

Like his uncle Jabez, Robert was a considerable antiquarian. He corresponded with John Horsley, and not only contributed to his magnum opus Britannia Romana, which was a work well known to the Baron (BJC, p. 258), but at Horsley’s behest he filled in many of the gaps in the text and relieved him of the burden of revising his manuscript and preparing it for printing. According to Chambers (1840, vol. 3), Cay was ‘an eminent printer and publisher at Newcastle’.[11] Certainly, Horsley wrote to Cay requesting advertisements he wanted placed in the Newcastle Courant in terms that suggest that Cay may have been in some way involved in the publication of that very newspaper (Hodgson, 1832, p. 444n). It also appears that in 1740 there was a William Cay who described himself as a bookseller in Newcastle and published an edition of the works of Allan Ramsay and others under the title The Caledonian Miscellany.[12]

If Robert Cay was indeed in the publishing business then he may well have been related to this William Cay. Burke, however, does not mention a brother William, nor does any William feature on the Cay Family Tree about this time. While neither of these sources can be considered as fully complete and accurate, the notion of Robert Cay actually being a printer and publisher, as well as antiquarian, brewer and salt manufacturer, could simply have been an error on Chambers’ part. The fact that Chambers and his brother were publishers themselves, and would have known something about who was who in the business of publishing and bookselling, makes the question all the more intriguing.

Even if Robert Cay was not involved in actually publishing Britannia Romana, he was still deeply involved in its detailed preparation, effectively as both its general editor and its copy editor. He likewise contributed to Horsley’s great map of Northumberland, and even gets a mention in the original citation:

A Map of Northumberland, begun by the late Mr John Horsley, F. R. S., continued by the Surveyor he employed [George Mark], and dedicated to the Right Honourable Hugh, Earl of Northumberland. By R. Cay, A. Bell, Sculpt. Edinburgh, 1753. (Hodgson, 1832, pp. 445−457)

In 1726, Robert Cay had married Elizabeth Hall, daughter of Reynold Hall of Catcleugh, which lies just 6km southeast of the Scottish border at Carter Bar. They had five children of whom four survived into adulthood. In 1754, Robert Cay was succeeded by his eldest son, John, who was born on 16 April 1727. Part of John’s education may have taken place at Edinburgh University, where his uncle, John, and great-uncle, Jabez, had studied law and medicine respectively. An Edinburgh connection would certainly explain a sudden move to Edinburgh later on. Having taken up the law, by 1756 he was a barrister at Middle Temple, London (Hodgson, 1832, p. 220), which is about the time of his marriage to Frances Hodshon, daughter of Ralph Hodshon of Lintz in county Durham (Cay et al., c. 1947, pp. 10−11), of whose family we will find out more in the following section.

John and Frances’ first son, Robert Hodshon Cay, was born in 1758, as far as we know, at North Charlton (Brown, 1910, p. 298). While John had been successful to the extent that his position in society was recognised by his appointment as a Justice of the Peace and then a deputy lieutenant for the County of Northumberland,[13] he entered into a lawsuit with the Duke of Northumberland that was his undoing. The lawsuit concerned the mining rights under his property and there would have been a reasonable chance of the rights being worth something since there were already many lucrative coal mines in the Newcastle area[14]. The Duke, at least, thought they might be worth taking for himself, for it was often the case that mining rights were reserved by the feudal lord. The upshot was that John Cay had to go to court to protect what was rightly his, and by the judgment given in August 1761 he did in the end succeed. The cost of the litigation, however, had put him in debt, for he had subsequently to flee north to Scotland and take refuge at the Abbey sanctuary at Holyrood (Figure 13.1; Brown, 1910, p. 241). As we shall later discuss more fully, his father’s brother and own namesake,[15] was a Steward of the Marshalsea, the infamous debtors’ prison in London, from 1750 to 1757. John Cay would have known only too well what his fate would have been had he ended up at a place like that, for a large proportion of its inmates simply did not survive the appalling conditions.[16] In addition, he would have been in the jurisdiction of the English courts, and would no doubt have been compelled to sell off North Charlton to pay his creditors. We may guess he had some prior knowledge of the Edinburgh Sanctuary, and the possibility that it afforded him both to stay out of prison and the clutches of his creditors. The rules of the sanctuary also offered him the chance to earn a living, and so that is where he decided to go.

At the time, the sanctuary at Holyrood Abbey was an area that extended some way around the edge of the royal park in Edinburgh.[17] Some of the old Sanctuary buildings[18] to the north-west of the Palace still exist, and the sanctuary boundary is now marked out by brass letters ‘S’ embedded in the causey[19] stone setts of the Abbey Strand. In ancient times it was a holy sanctuary available to all sorts of offenders but, by the latter half of the eighteenth century, it applied only to debtors. One of the more noteworthy recipients of its protection was James Tytler, balloonist and editor cum writer-in-chief of the second and third editions of Encyclopaedia Britannica (Henderson, 1899), whose stay there may well have been contemporaneous with John Cay’s.

Through his self-enforced exile in Edinburgh, Cay managed to hold on to his lands at North Charlton, but they were certainly mortgaged. His financial problems are referred to in his correspondence with William Ord (c.1715−1768), the High Sheriff of Northumberland andwealthy landowner; to whom he was in debt[.20]

John Cay died in 1782. There is no record of any Cay in the Edinburgh directories during his lifetime and so either John Cay remained in the Sanctuary for the rest of his life or he did not seek to publish an address that would give his creditors the opportunity of catching up with him. By 1784, his son Robert Hodshon Cay was living in Buccleuch Street, to the south of George Square. As noted in §12.3, Alexander Irving lived in a tenement at 5 Buccleuch Street before flitting to the Second New Town, as did John Playfair who lived at number 6; being close to the University, Buccleuch Street was a convenient place for professional people such as professors and lecturers to live and such people not yet beginning to forsake tenements for grander New Town houses. Despite his financial constraints, whatever the then were, John Cay had sent his son to Glasgow University in 1778 to study law, and by 1780 he had qualified as an advocate (Grant, 1944). Frances survived her husband John by some twenty-two years. By the time of her death in July 1804 at Fisherrow, a coastal village just to the east of Edinburgh, she had many grandchildren. Anglicans and Roman Catholics could not be buried at any of Edinburgh’s parish churches and so she was interred alongside her husband at St Margaret’s Church in Restalrig, shown in Figure 13.1 Just to the north-east of the Abbey Sanctuary. The gravestones in the family plot there are still clearly legible today.[21]

Given the pressures involved in having to live in a debtors’ Sanctuary and the problems that a Protestant−Catholic marriage would bring on them, John and Frances Cay would have had no easy time of it. we must therefore look into the origins of the Hodshons of Lintz to investigate how a Cay, being from a puritanical Protestant background, came to marry a Hodshon, from a line of highly devout Roman Catholics.

14.2 The Hodshons of Lintz

At first sight of the name, one could be forgiven for thinking that Lintz was a European place, and indeed Linz, pronounced in the same way, is the principal city of Upper Austria. But although the name Hodshon also seems a bit unusual, it does not look quintessentially Germanic; it is in fact frequently given as the more familiar Hodgson.

The River Derwent flows northeast from Lintzford to reach the River Tyne some 10km downstream, and from there the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle is only a further 7km towards the sea.

But think no more of Europe, because Lintz is a small village in County Durham that is only ten miles south and west of central Newcastle. The name Lintz was previously written variously as Linz, Lynths and Lynce, after the name of the early landowners there, of whom some snippets survive:

… given by William de Linz to Adam, fil. William de Linz … In 1350, Richard de Lynce held the vill of Lynce by homage … (Surtees, 1820)

In the same source, we are told that after the Lynces, the estate came to be the property of a family by the name of Redhough or Redheugh:

In 1391 Hugh, son of Hugh de Redhough, Chivaler, held two parts of the manor of Lynths.

From the Redheughs, Lintz eventually passed through the female line to one Edward Hedley, who held it in the 15th C., and by the second half of the 16th C. it was the property of his great-grandson, Nicholas Hedley, who married Elizabeth Hohshon. The name Hodshon is no less prosaic for it is a variation of the more common name, Hodgson, with which it frequently appears to be interchanged. If there is anything European about the Hodshons at all, it is that they retained their Roman Catholic faith throughout the reformation, the civil war, and the reigns of the houses of Orange and Hanover. They were a large family, see Family Tree 7, with many branches that had long been settled generally south of the River Tyne near Newcastle and Gateshead. In 1549, we find that a Richard Hodgson was Sheriff of Newcastle, and between 1555‒80 he had been the Lord Mayor on no less than three occasions. He died in 1585 leaving four sons and a daughter, the Elizabeth Hodshon who married Nicholas Hedley of Lintz, and it was thereby that Lintz came to be associated with eight generations of Hodshons thereafter.

As a result of Nicholas Hedley and Elizabeth Hodshon having no children, Nicholas took the step of entailing his property with the first line of succession going to Elizabeth’s brother William, followed by the third brother, Richard[22] In the event, it was Richard who succeeded, and from this gentleman, Richard Hodshon of Lintz, it passed down through three generations to the first Ralph Hodshon of Lintz.[23] This Ralph married Mary Killingbeck from Yorkshire but he died before 1715 leaving Mary; Ralph, his son and heir; and three daughters: Mary, Catherine, and Elizabeth, who all became nuns.[24]

After Ralph’s death, Mary Killingbeck remarried to a man called Hay who was a benefactor of the Bar Convent in York. While there may have been an element of wishing to provide for the young women by placing them in convents, it is clear the family were not only devout Roman Catholics, they were overtly supporting their Church at a time of religious persecution. However, as suggested by the local placenames in Figure 14.2, such as Priest Field and Priest Farm, Lintz may have been a predominantly Roman Catholic community.

Ralph and Mary’s son, the second Ralph Hodshon of Lintz, married and had at least three children: the first was his successor, the third Ralph Hodshon of Lintz (c.1730−1773), who had two daughters, Mary Agnes (d. 1782) who joined her aunt Catherine as a nun at Gravelines,[25] and Frances (1730−1804) who took an entirely different course by marrying John Cay of North Charlton in 1756.[26]

Having placed three of Frances’ aunts and one of her sisters in holy orders, a family as devout as the Hodshons of Lintz would naturally have wanted Frances to marry a Roman Catholic. How she came to know and marry John Cay, a Protestant, can only be guessed at. One possible hint is that the Cays and the Hodshons both had interests in coal mining, and Benwell, the origin of Jabez Cay’s Roman monument, happens to be the one place in the vicinity where it is possible that they were both involved;[27] unfortunately, we have no more ‘evidence’ than that to offer. Nevertheless, it would be reasonable to speculate that the marriage was the result of an elopement. Rather than become either a nun or a housekeeper to her parents, Frances may have preferred to run off with John Cay, despite the long shadow it might cast over their future.[28]

John’s parents may well have wanted him to make a marriage that would have helped to secure the family future, for example, by marring his cousin Grace (1722−?), eldest daughter of the aforementioned John Cay, Judge of the Marshalsea. But by his marrying Frances Hodshon, they would have been disappointed in their wish. Though scant, there is however some evidence to suggest that the true story is not as we would have expected, and that by marrying a Roman Catholic, John may have actually stood a chance of improving his circumstances. We shall look into this possibility at a later time, but on the face of it John and Frances had placed themselves in a difficult situation.

14.3 The Edinburgh Cays

John Cay and his wife Frances Hodshon fled to the Edinburgh Sanctuary about 1761 as a result of him being forced to mortgage his estate to cover the expenses of a lawsuit against the Duke of Northumberland over the mining rights on his land.[29]

After John’s death, and certainly by 1784, their son Robert Hodshon Cay (1758−1810) was living in Buccleuch Street, just to the south of Edinburgh’s George Square. Despite his financial embarrassment, John Cay had been able to send his son to Glasgow University in 1778 to study law. By 1780 Robert had qualified as an advocate and in 1788 he was appointed one of the four Commissaries in Edinburgh.[30] His parent shad wished him to marry his cousin Catherine Hodshon who, like his own mother, was a Roman Catholic.[31] This fact appears to compound the mystery surrounding why John and Frances would have chosen to marry across the religious divide, but in fact it explains it. In his family book, his descendant Albert Cay made a marginal note:

R. H. Cay above mentioned was heir presumptive of the estate of Lintz until Miss Catherine Hodshon was born. The family arrangement was that he was to marry her (his first cousin). She was a papist. (Cay et al., c. 1947, p. 15)

Catherine Hodshon (1761−1826) was the daughter of the third Ralph Hodshon of Lintz, Mrs Frances Cay’s brother. In this we have a clue to the likely answer to our conundrum: in this, the next generation, the parents wanted their Roman Catholic daughter to marry a Protestant. It was clearly a scheme to keep Lintz in the family at all costs by getting round the draconian anti-Catholic laws then in force. We may guess that it had been the same sort of motivation that led to John Cay marrying Frances Hodshon, for it seems that Frances must have been the presumptive heir to Lintz at the time of their marriage. In turn, their son Robert Hodshon Cay, born in 1758, was next heir presumptive until 1761, when Catherine eventually entered on the scene. The family then seems to have decided that the best remedy for this diversion of their tactics was to marry off Catherine to her cousin Robert Hodson Cay, whereupon the original plan would be back on track. But it was not to be, for in the end the match was unmade and they went their separate ways.

As asserted in note 23, Catherine Hodshon must have married about 1780, while Robert Hodshon Cay was married much later, on 26 October 1789, to Elizabeth Liddell, daughter of John Liddell of Dockwray Square in North Shields. Elizabeth was a talented amateur pastellist (Jeffares, 2014) who did the self-portrait shown in Plate 14.1 and the four portraits of her children, John, Robert Dundas, Jane on her own and Frances with Jane, that are now on display at 14 India Street. On their marriage, Robert and Elizabeth lived at 1 South George St (renumbered as 2 George Street in 1811). Their house is described as being:

… the fourth and fifth storeys of the tenement … consisting of a dining room, drawing room, kitchen, two bed chambers, and a bed closet on the first floor, five bed rooms and three light closets … two ceiled garrets, and one unceiled above, with four cellars and other conveniences. (Harris, 2011)

It was the last building at the east end of the street at the corner with St Andrew’s Square, with the entrance on the gable-end facing onto where the statue of James Clerk Maxwell now stands (Youngson, p. 208 [plan 28]). Unfortunately, like many of the First New Town’s original buildings, it was torn down to make way for 20th C. redevelopment, in this case a new building for the Caledonian Insurance Co. (later the Guardian Exchange) that was put up in the late 1930’s. A very fine building the new one may be, but any idea of what the the Cays house was actually can only be gauged from the one or two remaining gable-end properties in the area.

It would have been here that all but the youngest of Robert and Elizabeth’s children would have been born. On the last day of 1800, Robert was appointed Judge Admiral of the High Court of the Admiralty in Scotland (Plate 14.2), a significant promotion with an annual salary of £400, four times his salary as a Commissary (Cay et al., c. 1947, p. 15). The Cays, although not gentility like the Clerks, were apparently a well-to-do family that could now afford to move to a grander abode in the Second New Town, the development of which had more or less just begun. And so it was, for EPD (1804) lists them at ‘Heriot’s Row’, thereafter mentioned as 11 East Heriot Row. After renumbering in 1811, ‘East’ was dropped but the house number stayed the same. The house is very similar to 31 Heriot Row shown in Plate 2.5, but lacks the top floor that was added in later times. Instead, it has a dormer window, which is how Jemima Blackburn recalled number 31 being when she and her brother Andrew Wedderburn used to smoke ‘out on the leads’ there of a summer’s evening (Fairley, 1988)! The location of the house can be found in Figure 1.2.

Robert and Frances’ children were:

- John (1790−1865), friend of John Clerk Maxwell since their schooldays. He was Sheriff of Linlithgow and district and, like his friend John, a fellow of the RSE;

- Frances (1792−1839), who married John Clerk Maxwell and was, of course, the mother of James Clerk Maxwell

; - Robert (1/12/1793−1/9/1804), a midshipman on HMS Atlas, who died three months short of his eleventh birthday when his ship was off Demerara (Guyana); [32]

- Albert (1795−1869), originally a merchant who dealt in wine, tea and stocks and shares, he later became a news and advertising agent;

- Jane (1797−1876), James Clerk Maxwell’s maiden aunt who became a mother figure to him after her sister Frances’ death;

- Robert Dundas (1807−1888), a Writer to the Signet and Registrar to the Supreme Court of Hong Kong; he was named in memory of the brother who died in 1804.

Two others, George and Elizabeth, died in infancy.

Elizabeth Liddell and Robert Hodshon Cay were therefore James Clerk Maxwell’s maternal grandparents. From 1809 onwards, John Clerk Maxwell and John Cay both lived in Heriot Row and, being of a similar age and ideas, became close friends. It is not hard to see how this would lead to John Clerk Maxwell and Frances Cay becoming acquainted. The real question is, what took a relationship between them so long to develop and blossom? Jane Cay never married; instead she took a particular interest in her nephew James, especially after her sister’s death, and they remained close throughout his lifetime. According to C&G (p.14), Jane inherited her mother’s artistic talent, to which her two watercolours on display at 14 India Street amply testify. One is of her and the other of young James, each taking their tea in her sitting room at 6 Great Stuart Street.

While the Cays lived in St Andrew’s Kirk Parish, they did not worship there, for unlike the Clerks, John Clerk Maxwell included, they were Episcopalians. They were associated with the Charlotte Chapel in Rose Street and thereafter its successor, St John’s Church in Lothian Road seen in Plate 14.3 (Historic Scotland, 1970b; Harris, 2011).

The Edinburgh Cays had a close connexion with this Episcopalian church where Aunt Jane would take her nephew James for afternoon service, notwithstanding his attendance at St Andrew’s in George Street, a Presbyterian church, in the morning.

After Robert Hodshon Cay’s death in 1810, his widow Elizabeth stayed on in Heriot Row until her own death in 1831 when her grandson James Clerk Maxwell was just a month old. Although the family were ostensibly comfortably-off, on his death at the age of fifty-two, Robert’s estate was valued at only £900 (Harris, 2011). His father had never managed to clear the mortgage on North Charlton, and any hopes that Robert would be able to do so also went unrealised. The problem was left to his eldest son to wrestle with, and it may have been a factor in why, of the two daughters, Francis married late and Jane never married.[33]

14.4 John Cay, Sheriff of Linlithgow

The eldest son, John Cay FRSE (1790−1865), followed his father into the legal profession. He qualified as an advocate in 1812 (Grant, 1944), and from 1822 he was the Sheriff for Linlithgow and the surrounding area, some distance to the west of Edinburgh. John married Emily Bullock[34] in May 1819 (see Chapter 9), and from 1822 to 1831 they lived at 5 SE Circus Place, a very short distance from Heriot Row.

Following the death of his widowed mother in 1831, John Cay took possession of the family home at 11 Heriot Row and, presumably, rented out 5 SE Circus Place, for he returned to that address in 1847 while a variety of names appeared at that address over the intervening years. John was one of the first members of the vestry of St John’s Episcopalian Church in Lothian Road, which is very likely where he and Emily wed, for Bishop Sandford conducted the wedding and it was his charge.[35] Although Emily died at the young age of thirty-six, she and John had several children (Cay et al., c. 1947; Harris, 2011; Henderson & Grierson, 1914):

- John (1820−1892), eldest son and heir, became solicitor to the General Post Office in Edinburgh;

- Robert (1822−1888) went to Australia to become a sheep farmer, and died at Brisbane;

- William (1823−1840) died of influenza;

- Edward (1825−1870) went to Australia with Robert to become a sheep farmer. Died at Melbourne;

- Emily (1826−1904) married R. Robertson of Auchleeks, Perthshire;

- Elizabeth (1828−?) Married George Alexander Mackenzie of the Applecross family;

- Lucy (1829−1883?) married the Hon. Sir Montagu Stopford;

- Frances (1831−1832) was born just two months after James Clerk Maxwell and died aged one;

- Thomas (1834−1868) died of cholera at Rosario de Santa Fe, in central Argentina;

- Francis Albert (1836− ?) was the last.

Lewis Campbell described John Cay thus:

… though not specially educated in mathematics, was extremely skilful in arithmetic and fond of calculation as a voluntary pursuit. He was a great favourite in society, and full of general information. (C&G, p. 14)

John Cay was just two months older than John Clerk Maxwell, and they very probably attended the old High School together. They trained as advocates together, and as already mentioned from 1809 to 1818 they lived just a few doors away from each other in Heriot Row; their seemingly lockstep progress continued when in 1821 they were both elected fellows of the RSE within a month of each other. They were great friends and had many common interests, particularly in the progress of science and technology. John’s brother, Robert Dundas Cay, recalled that in 1821 or 1822 they were both:

… engaged … in a series of attempts to make a bellows that should have a continuous even blast … (C&G, pp. 7−8)

Campbell goes on to say:

[John Clerk Maxwell’s] acme of festivity was to go with his friend John Cay (the “partner in his revels”), to a meeting of the Edinburgh Royal Society.

and he later quotes from John Clerk Maxwell’s diary entry for Monday 2 March 1846:

Return [from the law courts] with John Cay, called at Bryson’s and suggested to Alexander Bryson my plan for pure iron by electro-precipitation from sulphate or other salt (C&G, p. 74n1)

while, in a letter to his son in February 1854, John Clerk Maxwell mentioned:

I am going to dine with John Cay, and with him proceed to the Royal Society. I may perhaps catch Prof. Gregory about the microscopist … (C&G, p. 207).

Campbell also gives several illustrations of John Cay’s interest in science, and of helping to encourage his nephew James Clerk Maxwell in these interests. For example, in October of 1844 James wrote home to his father:

I was at Uncle John [Cay]’s, and he showed me his new electrotype, with which he made a copper impression of the beetle. He can plate silver with it as well as copper. (C&G, p. 67).

James mentions him again in a letter to Lewis Campbell of July 1849 that further illustrates his scientific interest:

Perhaps you remember going with my Uncle John Cay ([when we were in the] 7th Class), to visit Mr. Nicol at [number 4] Inverleith Terrace. There we saw polarised light in abundance … Well, sir, I received from the aforesaid Mr. Cay a ‘Nicol’s prism’, which Nicol had made and sent him. (C&G, p. 123)

Modern times were emerging; railways, electric machines, electroplating, and photography. John would obviously have been interested in this last new wonder and so he joined, possibly even helped to found, the Edinburgh Calotype Club. The benefit to us is that for the first time we have a photographic record of our subject. He is seen seated, flanked by his two sons Robert and Edward, in a photograph taken by members of the Club (Plate 14.4).The picture was probably taken between 1843 and 1844, for the Club started in 1843, and there is also a photograph of his brother Robert Dundas Cay (q.v.) who left for Hong Kong in 1844.

Plate 14.4 : Early Calotype of John Cay, seated, with his sons Robert and Edward

The Albums of the Edinburgh Calotype Club , 19th C., vol. 1, p. 14)

(National Library of Scotland, non-commercial re-use)

For some reason or other, in 1848 John and family departed from 11 Heriot Row and returned to their original domicile at 5 SE Circus Place. By this time, however, John’s youngest child had reached twenty years of age and his daughter Emily had married in that same year, and so one of the factors may simply have been a case of ‘downsizing’ as a result of the family branching out. However, several factors conspired to precipitate a significant economic crisis about this time.Firstly, the potato famine of 1845 ran on, affecting not only Ireland but much of Great Britain. This, compounded by a failure of the corn harvest, caused the price of basic foodstuffs to soar. Lastly, the over-inflated prices of railway stocks collapsed. In the wake of this his brother Albert’s business foundered (see next section), and John may well have invested either in the business itself or in the stocks and shares Albert was dealing in, hoping thereby to help pay down the debt on North Charlton. Given this particular crisis on top of the general economic situation, it may simply have been the case that it impossible to repay the debt. Back in 1832, John Cay had said of North Charlton:

[it] has been a struggle for my grandfather and father to retain, chiefly in consequence of a grievous law plea with the Earl of Northumberland … I fear [it] will one day quit the family, for it is now heavily burdened and its owner [i.e., John Cay himself] has too numerous a progeny to admit of his making a wealthy squire of the eldest. (Bateson, 1895, p. 297)

Rather than using Charlton Hall as his own summer residence, he had already been renting it out to help service the debt (Parson & White, 1828, p. 389). And so it was that, late in 1847 or early 1848, 11 Heriot Row was given up[36] and not long thereafter, in September of 1849, the bulk of the North Charlton estate was put up for sale. It was advertised as being over 2,000 acres in area, bringing in an annual rental of some £1,280, and possessing a bed of coal of excellent quality (which clearly the Cays did not have the means to exploit to much advantage). Charlton Hall and Shepperton were purchased by a Mr William Spours of Alnwick, while John held on to those parts that remained (Bateson, 1895, vol. 2, p. 298).

After the Cays moved back to 5 SE Circus Place, 11 Heriot Row was occupied by a firm of solicitors. John Cay died in 1865 leaving an estate worth £10,000 (Harris, 2011) and so although his sacrifice of the family estate and the house in Heriot Row must have been bitter pills to swallow, he had not only stabilised the family’s financial situation but eventually left them fairly well -off (his father’s estate amounted to only £900). Of his children, John jnr qualified as a Writer to the Signet in 1851 and was Solicitor for the Post Office in Edinburgh. He married his sister-in -law, Geddes Elizabeth Mackenzie of the Applecross family in 1857; she was the sister of a Liverpool merchant George Alexander Mackenzie 12th of Applecross, who had just the year before married John’s youngest surviving sister, Elizabeth. John jnr and Geddes lived at first with his father at 5 SE Circus place. After his father’s death, however, John and Geddes moved to their lodge-house , called ‘Charlton’ in memory of the lost Cay family estate, which was at the east end of Strathearn Road, not at all far from where John’s Uncle Robert and Aunt Jane lived from about the same time. But after a year there the couple moved back into town, staying from 1867 in Alva Street, just off the west side of the Queensferry Road, and this later Charlton was either sold or rented out. There they stayed there for the rest of their days, with John dying in 1892 and Geddes following him in 1909. The remainder of the North Charlton estate was sold during John’s lifetime.

John Cay senior’s next three sons Robert, William and Edward, spent only a few years at the Edinburgh Academy, leaving at about the age of twelve. Robert was in the same class as Hugh Blackburn, who later married Jemima Wedderburn (Chapter 9). William attended for only one year and Edward went for two years in the same class as Charles Mackenzie (see note 32 of Chapter 2). William died in 1840, and a few years later Robert and Edward, seen in Plate 14.4 with their father, left for Australia to seek their fortunes as sheep farmers, for by then it was clear to John Cay that he could hardly provide a decent inheritance for even his eldest son. Some of the background to this comes from comments made by John Cay as reported in Bateson’s History of Northumberland (1895, p. 297). In addition, in a letter he wrote in the autumn of 1839 to his dying sister Frances,[38] perhaps looking for small talk to avoid the painful subject of her dire situation, he said:

Bob has been to some purchases of wool with one of his masters

& is going to make a trip to Liverpool. He is working at English wool which he says is mostly dirty stuff & is constantly jagging his fingers with the thorns in it. He says he is now a very fair sorter of Botany Wool & has a pretty good knowledge of it. His mind is plainly fully occupied with his businefs & his prospects & I have every hope he will do well, poor fellow.

Robert, at the age of 17, was not heading for any career that called for intellect, rather something more practical, wool trading. He was learning the basics of his trade somewhere in England, and perhaps emigration to Australia was already in mind. Why ‘poor fellow’? Was it that John Cay felt sorry for his son having to learn a dirty trade? Or was it that he could not bestow on him the sort of future he had hoped for; instead, Robert was planning to emigrate to the antipodes, a highly risky business at that time. Given that they posed with their father in the calotype above, this would be assumed to be subsequent to 1843 if the provenance of the Cay calotypes is accurate (q.v.). However, a death notice for Robert that appeared in the Melbourne Argus of 16 August 1888,[39] states that the year he arrived in Australia was 1842. Fox Talbot introduced the calotype in 1841, and so it is probable that these particular examples predated the formation of the Edinburgh Calotype Club,

Robert and Edward were certainly both about the age of twenty when they set out to be sheep farmers in Australia, and they seem to have been well established there by about 1850. Robert married Anne Montgomery from Melbourne in 1851 at Mount Fyans while in 1855 Edward married Anne Burdock, also in the state of Victoria. Furthermore, both men were appointed territorial magistrates for Avoca and the Loddon respectively, in 1852 (The Argus, 1852).[40]

The youngest son, Francis Cay completed only one year at the Academy and later followed his elder brothers to Australia (Henderson & Grierson, 1914, p. 141) but he may not have survived as there is no other mention of him. Edward died at Melbourne in 1870 at the age of only forty-five, while Robert died at Brisbane, having recently moved there from Victoria. Robert and Edward between them had twelve offspring to carry on a new generation of Cays that were firmly settled in Australia, and their descendants were still living in Queensland at the start of the twenty-first century.

All Sheriff John Cay’s sons went to Edinburgh Academy save for Thomas, who ended up in Argentina, as narrated on his memorial at Restalrig. The younger sons of John Cay may not have had the opportunity or the inclination for professional careers, rather they were pioneers and adventurers. If Robert and Edward had been intrepid in setting out for the Antipodes, at least it was populated in the main by their own countrymen. South America was an altogether different proposition. Prospects were there for certain in timber, cattle and many other commodities, but Thomas would have found it quite a culture shock. Rosario de Santa Fe lies on the navigable lower reaches of the Parana River about 200 miles inland of Buenos Aires, and is now one of Argentina’s largest cities. He was one of a dozen to die of cholera there during January 1868 (in the height of summer) and who were buried at the Methodist Episcopal Church (Howat, 2013). Thomas must have made some success of his brief life in Argentina, for although he was just thirty-three years old at the time of his death, the sale of his property fetched £2,000 net, paid to his brother John.[41]

14.5 Albert Cay, Entrepreneur

Sherriff John Cay’s younger brother, Albert (1795−1869), is not much mentioned in the usual biographies that touch on the Cay family, perhaps because, rather than belonging to one of the elite professional institutions, he was a businessman. Worse than that, he had the misfortune to have been made insolvent. While John had been forced by the general economic downturn of 1844‒47 to sell up 11 Heriot Row and the family estate at North Charleton (see §14.4), by late 1847 Albert’s wine, tea and stockbroking businesses had foundered and as a consequence his assets were sequestered by the courts on 1 February 1848 (Edinburgh Gazette, 1848). Until then he had had salerooms at 99 George Street (see Figure 1.2), and, at one time, a counting house in the port of Leith.[42]

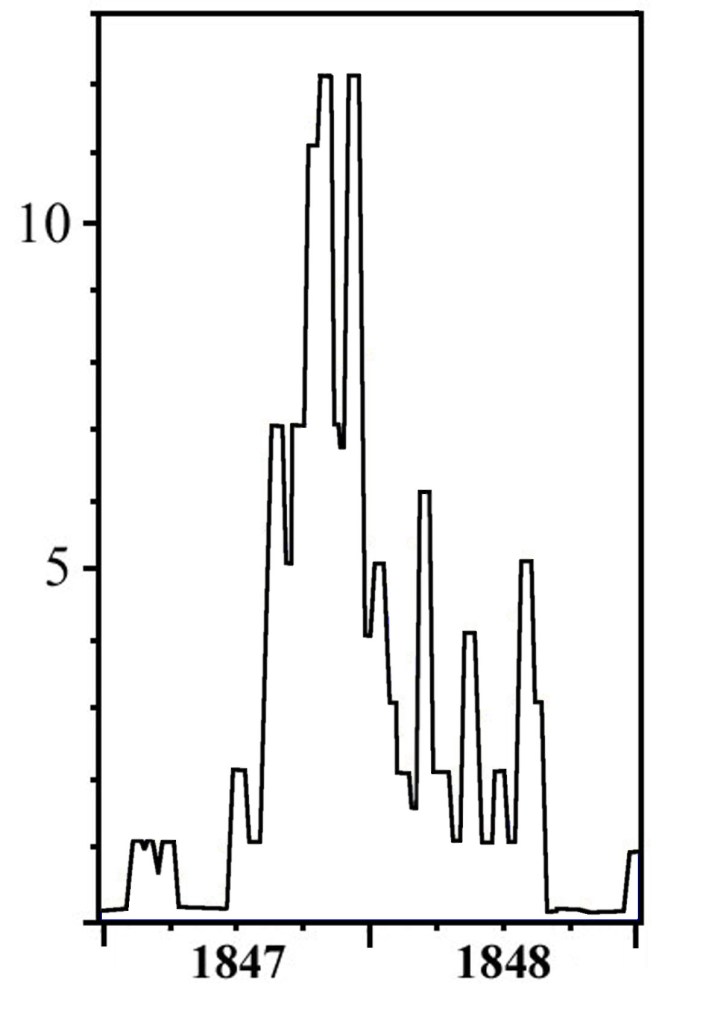

Figure 14.3 : Business failures 1847‒48

During 1844‒47, the UK was affected by several economic problems[37] which may have played a part in reducing the circumstances of several prominent members of the Cay family, and in particular in the eventual loss of North Charlton. This graph from Campbell (2011) depicts the weekly rate of business failures that were boosted by the failure of the corn harvest of 1847.

As already discussed in the preceeding section, several factors had caused a significant economic crisis at this time. By 1847, the crisis was in full swing and, as shown in Figure 14.3, record numbers of businesses failed, Albert’s amongst them . In spite of this, he had managed to set up and hold onto a partnership, Cay and Black, that traded as advertising and newspaper agents from another address in George Street.[43] He was discharged by the courts a few years later and his new business survived under his business partner until it was eventually taken over by Keith’s advertising and newspaper agency, which lasted into the early 1900’s (EPD, 1887‒1911).

Figure 14.4 : Advertisement in the 1887 Edinburgh Directory for Keith and Co.

They were obviously happy to point out that their advertising and newspaper agency was founded on the successful business of Cay and Black .

Albert must have been a larger than life fellow and had his fingers in many pies, earning himself the soubriquet Albertus Magnus (Frey, 1888). In addition to his businesses, he was a member of the Royal Company of Archers (like his brother John he won many of their prize competitions) and was director of the Highland Club of Scotland (c. 1825) and of the Church of England Life and Fire Institution (c. 1844). As to residences, from 1846 he gave his address as Fixby Cottage in Corstorphine;[44] from 1849 Slateford House; and from around 1853 Ratho Villa. It is doubtful that he owned the properties.[45]

Previously, when his brother John had taken over 11 Heriot Row as his family home, Albert moved with his youngest brother Robert and his sister Jane to 6 Great Stuart Street, a property comprising some flats entered from a common stair (Plate 2.4; Figure 1.2), and lived there till 1835, the year of Robert’s marriage. It is understandable that this event necessitated further residential changes; in the same year, Albert had moved his wine business from 37 to 99 George St, where it is possible that he also had a flat, for he is listed only at that address until the demise of his business. Thereafter he listed himself either at his out of town address or at Cay and Black. In his later years his eyesight began to fail; he moved in with Robert and Jane (see §14.8) and eventually became blind.

14.6 Dyce and Cay

Robert Dundas Cay WS (1807−1888), the youngest child of Robert Hodshon Cay and Elizabeth Liddell, was born at the family seat of Charlton Hall (Cay et al., c. 1947, p. 26) and brought up at 11 Heriot Row where the Cay family had lived since 1804. As a boy, he must have been familiar with the Clerk family at 31 Heriot Row, and later with the Wedderburns who moved there in 1821, but if not, they would soon have come to his attention when John Clerk Maxwell started courting his older sister Frances, whom he married in 1826. In 1831, the year James Clerk Maxwell was born, Robert would have been in his early twenties.

William Dyce RA (Barringer, 2004; Ferguson, 2006) was born in 1806 and therefore of a similar age to Robert Dundas Cay. He enters our story possibly because Robert had a gift for drawing and painting, as did his mother and younger sister (C&G, p.14; Cust, 1888). [46] For whatever reason, he and William became firm friends. William had been born into a well-off Aberdeen family; his parents were the distinguished physician Dr William Dyce FRSE of Fonthill and Cuttlehill and his wife, Margaret Chalmers of the Westburn family.[47] Educated at Marischal College in Aberdeen,[48] William graduated with an MA at the age of only sixteen. Though talented in drawing and painting, at first he followed his father’s wishes by studying medicine. Tiring of that, however, he turned to theology with the aim of becoming a priest with much the same outcome.

In the meantime, William not only continued drawing and painting but sold enough of his work to afford his passage to London in 1825. He contrived to meet the president of the Royal Academy, who was impressed enough with him to intercede with Dr Dyce to allow him to study at there as a probationer. For William, however, even such good fortune as this was not enough, and soon thereafter he accepted the offer of Alexander Day and William Holwell Carr, both painters and art collectors over thirty years his senior, to visit Rome, where he spent nine months during 1825 to 1826 studying, in particular, Titian and Poussin before returning to Aberdeen. The following year, at just twenty-one, he exhibited at the RA[49] after which he returned, as a nascent pre-Raphaelite, to Rome.

While in Rome, William’s 1828 painting Madonna and Child made such an impression on the members of the German art community there that they offered to finance him to stay on by buying it at a handsome price. Considering that he had taken an MA at sixteen and had then flung himself in at the deep end as an artist, within half a dozen years he had reaped the critical acclaim of both the Royal Academy and the European cognoscenti. Nevertheless, the painting may have been unfinished later that year when William was back home in Aberdeen. All too predictably, the straight-laced inhabitants of the Granite City did not find much enthusiasm for his chosen style, and even less for his subject matter, Madonnas. Amazingly, however, he spun once again on his heel and headed back to Marischal College to study the emergent subject of electromagnetic theory! This was no immature flight of fancy, for he came away with the Blackwell prize for his essay entitled The Relations between the Phenomena of Electricity and Magnetism, a concept that was only just then beginning to be appreciated. But the change of direction was short-lived and he turned again to art, this time as a portrait painter, which in contrast to his attempts with Madonnas, was showing some early signs of success.

In order to pursue this as a career, in 1830 he moved to Edinburgh, perhaps staying at first with his sister Margaret, who had married an Edinburgh solicitor by the name of James Ross some years before.[50] He then moved to 128 George Street where he lived with his younger sister Isabella, who was no doubt sent to look after him. It is said that Dyce’s portraits of ladies and children were much admired and, by his own account, he had no shortage of commissions. Dyce was elected to the RSE on 2 April 1832, at not yet twenty-five years of age, a considerable accolade for one so young[51].This could hardly have escaped the attention of John Clerk Maxwell and John Cay, who were already fellows of some years standing and regular attenders at its meetings.

In the summer of 1832, the Clerk Maxwells took young James with them for a vacation at Nether Corsock, which must have been his first visit there. The couple were clearly already on friendly terms with Dyce, for they invited him to come along. He did some of his earliest recorded watercolours there, none of which survives (Pointon, 1979, p. 21).

Not one of the original watercolours he did in 1832, but a later one from his second visit to Nether Corsock in 1835. The only loch on the Glenlair estate was Loch Falbae. If the view was taken from Upper Glenlair looking north, this loch would then have been in the middle distance, with nearby hills to its left and in the far distance to its right. This corresponds reasonably well to Dyce’s image.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Dyce evidently enjoyed the experience, roaming the hills and moors and letting his artistic eye take in the wild scenery, visiting Threave and, by walking a total distance of some forty miles, the Abbey at Dundrennan, which he sketched and later painted. It is believed that Dyce hung onto these early works for sentimental reasons, but they were all lost after being sold off after his death (Pointon, 1979, p. 22).

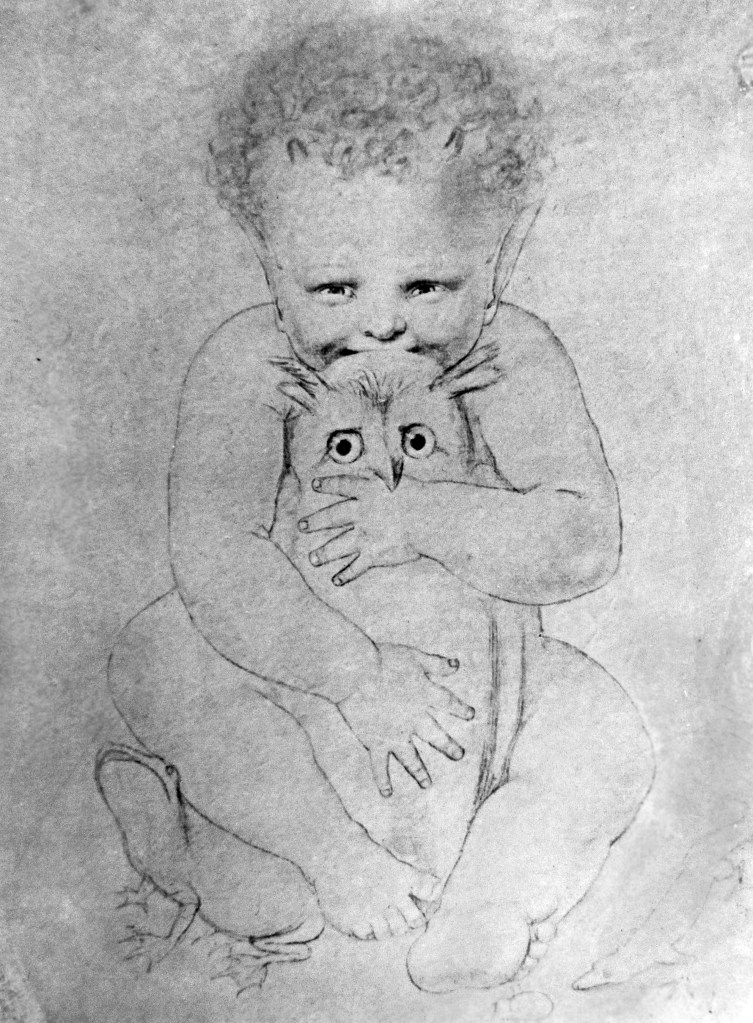

Plate 14.6 : Dyce’s Charcoal Sketch of James Clerk Maxwell as a child, c. 1832‒4

Compare with a similar 1825 version below.

From the copy presented to the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation by Mr. Giles, Canada and Miss Barbara Wallis, Cambridge.

Plate 14.7 : Dyce’s Charcoal Sketch of Puck, 1825

Possibly the first of several he did in this vein, the one of James Clerk Maxwell above being just one of them.

CC0 – Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections.

Sometime between 1832 and 1834, Dyce drew a charcoal sketch of James Clerk Maxwell as Puck in the same style as his original version from 1825 (Plates 14.6 and 14.7 above). A copy of the sketch of James is on display at 14 India Street. In the will of Mrs Barbara Wallis,[52] James is given as being three in the sketch, but he looks much younger. While Dyce was at Nether Corsock in 1832, he would surely have favoured his hosts with some sort of memento and the age of the child in the sketch could well be fifteen months, consistent with a date of 1832.

It was by 1834 at the latest that William Dyce had got to know Frances’ brother Robert Dundas Cay. In October 1834 we find the budding artist William Dyce in financial difficulties and writing to Robert Dundas Cay for help (see §14.6). The problem was not that he did not have enough money, but just like merchants and tradesmen, he could only get money as and when a client paid their account. Referring to his new friend Robert as ‘My dear Cay’, he says:

…when I have perhaps been most in want of a supply of the ready, I have been unable to procure any but at the expense of dunning (as I have said) some employer [client] ;…which… has been detrimental to my interests… (Dyce & Dyce, pp. 116−119)

He therefore badly needed to open a bank account but the problem was that he needed two guarantors to stand security for him. He complained that he was not known in Edinburgh and his brother-in-law, James Ross SSC, would not vouch for him because they had quarrelled. He needed Cay, as his only other friend in a position to help, to stand guarantee for the sum of £200, along with his own father Dr William Dyce (ibid.) who would actually underwrite any financial risk to Robert. One presumes that Robert did vouch for Dyce, for he had taken a fancy to Isabella, the artist’s sister, and married her almost exactly one year later!

While Dyce probably became acquainted with Robert and the rest of the Cay family as a result of having already met John Cay and John Clerk Maxwell, and then Frances Cay, it has been suggested that they may have come to know each other through the Edinburgh Calotype Club (Melville, 2006, p. 92), of which Robert’s elder brother John was a member. This, however, is erroneous, for the two men were corresponding by the autumn of 1834 and the club was not founded until, at the very earliest, late 1842. On 14 October Dyce wrote to Robert:

‘I daresay Isabella has told you of my having been in this town for three or four weeks enjoying a little repose after my London campaign’ (Dyce & Dyce, p. 113; Cay, 1888)

The ‘London campaign’ refers to his exhibition of three paintings at the Royal Academy, among them his portrait of Sir George Clerk of Penicuik. But it is the reference to Isabella that is significant, for we learn that Robert is now corresponding with William’s sister. She also appears to have been back in Aberdeen at this time, for William mentions that he is going to do her picture in pastels before he returns to Edinburgh:

She means to give you an agreeable surprise … My mother and father and all here join in kindest remembrances and one individual in something more warm’ (Dyce & Dyce, aft.1864, p. 114, my emphasis).

There was a similar cryptic message for Robert in his letter of 22 October:

Kindest remembrances from everybody and love from somebody. (ibid.)

It certainly seems to imply that there was more than mere letter writing going on between Robert and Isabella!

That winter found Dyce commissioned by Robert and Jane to paint Frances sitting with her young son James (Plate 2.2), for which he was paid £31 10s in March 1835 (ibid.). Dyce had begun the painting probably when Frances and John were on their winter visit to Edinburgh, but he took ill before it was finished and in the interim the Clerk Maxwells had to return to Nether Corsock, and so he had to make the trip there later in the year to finish it. Since he seems to have enjoyed his first visit there three years before, it was a diversion that he probably had no regrets about. At that time recovery from a serious illness could take quite some time so that he very likely got behind in his commissions, which concurs with the fact that he was not able to get to Nether Corsock to finish the portrait till the late summer. [53]

It was on this visit that he did the watercolour which did survive, Glenlaer (Melville, 2006, pp. 90−91; Plate 14.5). he was still there on 18 September when a letter arrived from Robert announcing his engagement to Isabella. William recounts this in his reply to Robert in jubilant tones, telling him that the laird, John Clerk Maxwell, had left his mantle of earnestness aside for long enough to send up a rousing three cheers, leading in the hip-hip-hoorays himself. Jane Cay must have been there also, for it was a ‘Miss Cay, rosy as the morn’ who brought him the letter.[54] He ends by saying the portrait had gone remarkably well, and Robert’s sister (Jane or Frances?) had hopes of William himself beginning to do better in ‘matters pertaining to the fair sex’.

During his stay in Edinburgh, William Dyce got to know some of the trustees of the Board for Manufactures (see §8.14) whose secretary was then James Skene of Rubislaw[55] a fellow Aberdonian and devotee of art and design, and so began to get involved in the design activities of its drawing school (also §8.14). If this seems an odd thing for a portrait painter to be involved in, Dyce was in many respects a polymath, hints of which have already come out in his volte face from art to electromagnetic theory and back again. He also wrote essays on an eclectic range of subjects from the garments of Jewish priests, to the Jesuits and church music. While it may be recalled that Baron Sir John Clerk and his son George Clerk Maxwell had both been trustees of this Board for Manufactures when its concerns were foundational industries such as whaling, spinning and the manufacture of linen, by now its aims had had been redirected to promoting a drawing school with the emphasis on turning out skilled artists, draftsmen and craftsmen who would go on to conceive and design goods and works of the highest quality. Dyce became in effect a consultant to the Board, in which capacity he eventually became very active. During his last year in Edinburgh, he submitted his ideas to Lord Meadowbank (Dyce, 1837), which then led to him being asked to take up a similar but more wide-ranging role in England.

Dyce moved back to London in 1838 on his appointment as Director of the School of Design at Somerset House, but he did not marry until 1850. His wife, Jane Brand (1830−1885), nearly twenty-five years his junior, was from a Kinross-shire family that had settled south of the Thames at Balham, Surrey. They had two daughters and two sons. Dyce was now setting up design schools for the Board of Trade, whose vice-president in 1841 was William Ewart Gladstone;[56] the two men became close friends. not only did he continue to paint, he designed coins and medals and made frescoes for galleries and, in particular, for the Queen’s Robing Room; he wrote on theological matters and was at the fore of the Anglican High Church movement; he was a talented organist and composer, and founded the Motet Society; and he published The Book of Common Prayer with the Ancient Canto Fermo set to it at the Reformation. In all of these areas, and others, he wrote numerous essays and pamphlets, much of which was transcribed and kept by his son James Stirling Dyce (Dyce & Dyce, aft.1864) whose name suggests that Dyce also had maintained an interest in and admiration for mathematics.

After his death at Streatham on 14 February 1864, Dyce’s friend Gladstone said of him that he had exhibited the ‘very ideal of the profession of an artist’. such praise does not go far enough: wonderful and enduring artist though he was, he was nevertheless a man of considerable talent who could have achieved great heights in many fields. Compared with his art, his pioneering efforts in the setting up of the design schools in Edinburgh, Somerset House, Spitalfields and Manchester over the years 1837 to 1848 are now little remembered, but they are equally important in terms of their long-term benefits to the nation. Laying down the key principles of applying design to technology and the furnishing of schools that could turn out skilled designers to embody these principles provided the foundation for a multitude of inspired Victorian creations that are still to be marvelled at today. While the Forth Bridge (1893) is a prime example that reaches the very apex of these ideals, it is only one of countless bridges, buildings, steamships, steam-engines and so on, all the way down to cups, saucers and coinage, where the benefits of these principles were demonstrated. Technology has moved on, but the principles remain.

14.7 Robert and Isabella

Robert Dundas Cay and Isabella Dyce, seen in Plates 14.8 and 14.9, were married in Aberdeen on 29 October 1835 by the Reverend John Murray, ‘minister of the North Parish, Aberdeen’.[57] The witnesses were the bride’s uncles on her mother’s side: Alexander Brown, [58] bookseller and sometime Provost of Aberdeen, and David Chalmers, a printer. The Dyce and Cay families were Episcopalian, yet they were married by a Presbyterian minister. Dr John Murray of the North Parish was not only a Presbyterian, he was one of those principled ministers who came out for the Free Church in 1843 and took his congregation with him (Scott, 1926). But he officiated at the marriage because he was one of the family, for he was married to Isabella’s cousin, Margaret, on her mother’s side.[59] We may adduce that the Dyce side of the family were Episcopalian because a number of William’s siblings were baptised in that faith.[60] On the other hand, it seems highly likely that the Chalmers side was Presbyterian, for it would be very difficult for any clergyman to take a wife who belonged to a fundamentally different denomination.[61] A separate indication that the marriage of William Dyce MD and Margaret Chalmers was a unison of the Episcopal and Presbyterian faiths is that their son William, was baptised by a Presbyterian minister.[62]

What this clearly demonstrates, however, is that even though matters of religion were still taken very seriously, and the principle ‘each unto his own’ was still very much the order of the day, by the early nineteenth century Episcopalians and Presbyterians were not only getting on well with each other socially, they intermarried, as did, for example, John Clerk Maxwell and Frances Cay, and Isabella Clerk and James Wedderburn (Fairley, 1988, p. 98), and here we have two Episcopalians, Robert and Isabella, being married by a Presbyterian minister. Although discrimination against Roman Catholics was still endemic, the days when the nation was close to tearing itself apart over the issue of episcopacy were largely over.

Plate 14.7 : Robert Dundas Cay

From the Albums of the Edinburgh Calotype Club of which he was a member (Edinburgh Calotype Club, 19th C, vol.1, p. 55) . CC0 National Library of Scotland.

Plate 14.8 : Isabella Dyce

Painted by her brother William Dyce in 1832 when she was about 21 years old.

CC0 – Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections.

Having qualified as a Writer to the Signet in 1833, Robert was a clerk to the Court of Session before being promoted to Keeper of the Rolls in the year of his marriage; he would therefore have had a comfortable income. He left 6 Great Stuart street to live with Isabella at 18 Rutland Street,[63] which turns off Lothian Road opposite the entrance of St John’s Church, and here they started to raise their family of eleven children:

- Robert Hodshon, baptised 27 October 1836;

- William Dyce, born 28 March 1838;

- Elizabeth, born 14 April 1840;

- Charles Hope, born 26April 1841;

- John Frederick, born 2 November 1842;

- Alexander Dyce, born 7 May 1844, died 22 February 1853;

- Albert, born 1846 in Hong Kong (as were the children that followed);

- George D’Aguilar, born 1848, died 1881 (he was named after the retiring Lieutenant Governor of Hong Hong);

- Margaret, born 1849, died 1921;

- Isabella, born 1850, died 1934;

- Dundas, born 1851 and died in the same year.

The year 1844 brought a momentous change, for Robert secured a position as a civil servant in Hong Kong. It was an adventurous step to take, particularly since Hong Kong had become a British colony only a few years before. It was halfway round the world and foreign in all senses of the word; language, culture, religion, climate and food being just the obvious ones. His motivation for going may have been to improve his prospects, perhaps to help restore the family fortunes, but the loss of the office of Keeper of the Rolls, which had lapsed in 1841, may also have been a setback he needed to recover from. But he had a wife and five young children to consider. Unlike the situation that prevailed in India, they would not be able to rely on the benefits of a well-established colonial settlement. Nevertheless, it showed enterprise on his part, for in gaining a toehold in the legal system there, he would be playing a key role, and perhaps in the long-run he would have ample opportunity for advancement.

Hong Kong and its dependencies were declared a separate colony by a Royal Charter of 1843 that established full legislative powers, and the law courts to enforce them, under a plenipotentiary governor, Sir Henry Pottinger HEICS, who had already been Superintendent of Trade and Her Majesty’s Plenipotentiary since the formal cession of Hong Kong to Britain by China at the end of the Opium War in 1841. He was formally appointed as the first governor on 5 April 1843. While Robert had started preparations to move a whole world away, the organisation of a proper colonial administration in Hong Kong had only just begun to get under way. In the first couple of years there was much that needed to be done and too few adequately qualified people to do it all. Mistakes and misunderstandings contributed to the stresses and strains of this crucial period, and so when Sir Henry put forward his resignation it was accepted, no doubt as much to his own relief as that of his officials and a grateful British government. More manpower was needed to fill the gaps in the administration, and so it was that Robert sailed for Hong Kong in early 1844 as one of the fresh appointees sent out to build up the manpower of the administration and to get things going.

No doubt Robert had discussed at length with Isabella and his family whether she should accompany him at the outset or come out after he had managed to get settled and had time to consider whether or not his great leap into the unknown had been a good idea. Bearing in mind that they had by now several children, one would have thought the upshot would have been that he would have gone alone, but according to (Norton-Kyshe, 1898, p. 325) they sailed together:

This lady [Mrs Cay] had arrived in the Colony at the same time as Mr. Cay, in May, 1844

However, there is a more reliable record[64] that proves to the contrary, that he did sail alone:

__12th [October 1844]__

Cay ‒ Robert Dundas Cay, Writer to the Signet, Registrar of the Supreme Court;

of Hong Kong in China, and Isabella Dyce his Spouse, had a Son

Born in No 18 Rutland Street and was baptised this Parish, on the feventh May last ; Named —

Baptised on the Twenty Sixth of June thereafter by the Revd Berkeley

Addison, Curate of St John’s … Episcopal Chapel, Princes St, Edinburgh. [65]

The day that this unnamed child was born was the very day that Robert sailed into Hong Kong harbour on HMS Spiteful. The record is unequivocal as to where the child was born and baptised and so Isabella must have stayed behind.[66]

Robert had set off early in 1844, sailing to Bombay in stages via the Mediterranean and Red Seas by crossing Suez over land.[67] He then departed from Bombay on HMS Spiteful in the company of the newly appointed governor, His Excellency John Francis Davis, who was to relieve the incumbent Sir Henry Pottinger, and Frederick Bruce, the new Honorary Foreign Colonial Secretary (Norton-Kyshe, 1898, p. 47). They arrived on 7 May and were sworn in by the Legislative Council of Hong Kong the following day. By October things must have been going well for Robert, for he was appointed as a Commissioner for Taking Affidavits and was also provided with a deputy, Mr Smith.

There were many teething troubles in the new administration, and things were exacerbated by a rift between the governor and his Chief Justice, John Hulme. There was also a serious problem with the mail, for the local Postmaster General proved to be not only incompetent but highly irrational. after being suspended from duty in July 1845 he ended up committing suicide (Lim, 2011, pp. 114−115). Problems with the administration were one thing, but everything depended on the mail. Everyone would have been frustrated by the mail debacle for not only did it hamper their work, communications with home were difficult enough at the best of times. Robert must have longed to know whether Isabella and his new child were alive and well, but five months after the child’s birth his name was left blank on the baptismal certificate. A letter would no doubt have been sent to Robert in all haste to inform him of the child’s birth, but even so Isabella would have been lucky to hear by Christmas[68], meaning getting a reply might take as long as six months, but with a dysfunctional postal system things could have been even worse – no reply at all. This may well offer an explanation as to why the birth of the new arrival was recorded so long after its birth, and why no name was given at the time. Eventually Alexander Dyce was the name that they chose.

When it was decided that it would be safe for Isabella and the children to come out, preparations were made to depart for Hong Kong in early 1845, for she arrived in the following July having brought with her two female servants, three sons and a daughter (Lim, 2011, p. 270). Now, while the daughter could only have been Elizabeth, at the time of Isabella’s departure she had five sons: Robert, William, Charles, John and finally Alexander, who was less than a year old. Nevertheless, Lim is correct for, as we shall soon discover, the two eldest sons were left at home.

Safely reunited, they all moved into a house called Rosehill within the security of the administrative quarter. By and by the establishment of the administration was progressing and when, in January 1847, the formation of the Admiralty Court was announced, Robert was appointed as its Registrar, following which, in 1848, he was appointed Master in Equity, that is to say, he could handle cases relating to the valuation of land and property in his own right. In the meantime, more children came along: Albert, George, Margaret, Isabella and finally Dundas, who died in infancy. Unfortunately, Alexander, who journeyed out to Hong Kong as an infant, developed spinal weakness and was sent home in 1848, where he died in 1853.

Otherwise, things seemed to be moving along on a level keel until 1852, when Robert’s world was suddenly shattered by Isabella’s death in a carriage accident at Victoria:

The Registrar of the Supreme Court, Mr. Robert Dundas Cay, on the 21st June, had to deplore the loss of his wife whose death took place at Victoria, on that date (Norton-Kyshe, 1898, p. 325)

She was buried at Wong-We-Chung, Happy Valley Cemetery, Victoria, alongside her infant son Dundas who had died the year before, ‘in the centre of the largest plot for an individual grave in the entire cemetery’ (Lim, 2011, p. 115).The inscription on the memorial is simply:

Sacred

to the memory

Isabella Dyce

1811 − 1852

beloved wife of

Robert Dundas Cay

Rosehill, Hong Kong

and their infant son

Dundas 1851

After burying Isabella, Robert must have wondered, in his grief, what he must do. He no doubt had servants and maids who could look after his children in the short term, but there was no mother figure, and no help from family and close friends, as there would have been at home in Edinburgh. In the face of this woeful situation, Robert wrote home. Assuning that he would get a reply back from Edinburgh by about January the following year, 1853, he had a few weeks to set things straight in Hong Kong, get permission for a substantial leave of absence, and get a passage home:

Mr. Cay, the Registrar of the Supreme Court, proceeded on leave of absence on the 24th March [1853] (Norton-Kyshe, 1898, p. 332).

With nine children and some maids to look after them, it might have been difficult to book a passage for all of them at one time, both for financial reasons and availability of berths; we do not know how he managed, save to say they all got safely home, perhaps by the summer of 1853. About a year later it was recorded that: