Brilliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

13.1 Patrick Anderson’s Legacy

13 Dr Thomas Weir and Anderson’s Patent Pills

In this chapter we explore in more detail the family connections and dealings of Dr Thomas Weir, father-in-law of the first George Irving of Newton, for they reveal a surprising and rather interesting story. Dr Thomas Weir, great-grandfather of Janet Irving, and thereby three-times-great grandfather of James Clerk Maxwell, was from 1686 the possessor of the secret recipe for Anderson’s Pills, a favourite patent remedy and ‘cure-all’ that endured both in the United Kingdom and overseas for over 200 years. Family Tree 6 will be helpful in following the connections involved in this story.

It has been mentioned before that Dr Thomas Weir married Bethia Blackwood, a daughter of Robert Blackwood of Pitreavie[1]. They married sometime before 1692, for they had a child who died in that year (Paton, 1902, p. 681); sadly, two more died in 1697 followed in just a few weeks by Bethia herself. However, they did have at least one surviving child, a daughter by the name of Sarah, and it was she who in 1711 married George Irving of Newton. Although a connection has not yet been established, the author suspects that George’s father-in-law, Dr Thomas Weir, was probably related in some way to George’s uncle, John Weir of Newton, but whether or not that was the case is not really germane. Now, on Bethia’s side, the Blackwoods of Pitreavie are not directly related to the Weirs of Blackwood, rather they are connected with the Blackwoods of Ayr (Paterson, 1847). There is a possible connection, however, between all three, for William Weir of Blackwood, who was alive about this time (see §11.2 and footnote 13 thereto), was known alternatively by his stepfather’s surname as William Lowrie of Blackwood, and for yet another reason, he had a third alias, Robert Blackwood (Cobbett, 1811, p. 1025)! He could therefore claim or deny being related to the Blackwoods as and when it suited him.

13.1 Patrick Anderson’s Legacy

We now take a step back in time; Corley (2004) inform us that Patrick Anderson (c.1580−1660) was a Scottish doctor, author and manufacturer of patent medicine. By 1618 he was well-known in Edinburgh, and in 1625 he was appointed as a physician to Charles I, which may mean no more than he had the right to use the royal warrant in association with his profession. In 1635 he published a treatise Grana Angelica as a means of promoting his own patent digestive pills (Wootton, 1910), which were reputedly an excellent remedy for hangovers. Of ‘walnut’ size and made with aloes, colocynth and gamboge, he claimed to have registered the formula in the Rolls House at Edinburgh after bringing it back from Venice around 1630, but the record seems to be no longer extant[2]. Eventually known as ‘the Scots Pills’ or ‘Anderson’s Pills’, they were also apparently favoured by a subsequent monarch, Charles II.

There are several versions of what happened to the pills after Patrick Anderson, but the most detailed account is given in Chronicles of Pharmacy (Wootton, 1910, pp. 168−170). After Anderson died in about 1660, the formula and rights went to his daughter Katharine who continued to sell the pills in Edinburgh, while about the same time another Edinburgh doctor, Thomas Weir MD[3], took over Anderson’s medical practice and in 1686 also bought from Katherine the formula and the wherewithal to manufacture and distribute the pills.

Chambers (1980, p. 27), however, states that Thomas Weir was probably the son of a second daughter of Anderson’s by the name of Lilias and so, Katherine being his aunt, he came by the rights through that relationship.connection. But there is nothing to stop both versions being correct, for Weir could simply have bought the rights and requisite paraphernalia from his aunt Katherine after the death of his mother. This would also explain why Weir had become involved in Anderson’s practice in the first place, for Patrick Anderson would then have been his grandfather. Whatever the circumstances, Dr Weir obtained royal letters patent from King James VII for Anderson’s Scotch pills in 1687 (Scotland, Privy Council, 1687)[4] but, in an attempt to assert its authority over the monarchy, the English Parliament soon thereafter revoked all those royal warrants that had been granted without its specific approval. Dr Weir was therefore forced to seek such protection as he could for his monopoly from the new monarchs, William and Mary, (Scotland, Privy Council, 1694) and from Edinburgh Town Council, which he obtained by 1694.

Unfortunately, the protection that Dr Thomas Weir managed to obtain was not wholly watertight against others who also claimed to have the rights to the recipe. One, Mrs Isabella Inglish, was said to have stolen the recipe when she had been a servant in Weir’s household; not only was she selling the pills in London with apparent impunity, she was even advertising the fact in the London Gazette (Inglish, 1689):

Advertifements,

THese are to give Notice, That Dr. Anderfon’s or the Scotch

Pills, (which is a convenient and effectual Medicine both

by Sea and Land, have been much abufed fince the Death of Mrs.

Catharine Anderfon) and are now faithfully prepared and fold only

by Mrs. Ifabel Inglis, living at the Hand and Pen near the Royal

Bagnio in Long-Acre, London.

Even though she was libelled as (alleged to be) a counterfeiter in Edinburgh in 1690, Mrs Inglish continued to trade the pills in London and was selling them at the Unicorn in the Strand, c.1707−09. For long thereafter, her son James, and followed in turn by his son David, were continuing the trade from more or less the same location and still regularly advertising them in the London Gazette as being the ‘true pills’ right up to the start of the nineteenth century (Inglish, 1800).

Another ‘pretender’ to the pills was someone by the name of Thomas Steill, who claimed to have got the recipe from Anderson himself through a Mrs Hastie:

In the action anent Anderson’s Pills, betwixt Weir and Steill, Mrs Hastie, who gave the secrets thereof, and gave it to Steill, depones, she had it from Mr Anderson ; and so both were allowed to sell the same. (Fountainhall & Scott, 1822, p. 237)

These pills, selling at the princely sum of one shilling per box in 1748, were therefore highly in demand; at about £6 in today’s terms, they were the basis of a lucrative business.

13.2 Milne’s Court

Thomas Weir conducted his Anderson’s pills business from a house in Miln’s (now spelled as Milne’s) Court (Chambers, 1825, pp. 255−257; 1980, pp. 27−28),a tall tenement on the north side of Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket facing the head of the Upper Bow (see Plates 13.1 (a) and (b)). The building still stands and dates from 1690, just about the time when Thomas got protection for his remedy from the Town Council. The entryway is just two doors down from the long-established Ensign Ewart pub, where Thomas’ customers may well have desired to wash down the bitter pills they had just bought with a glass of ale.

‘… the second flat of this land was … entered by an outside stair, giving access to a shop kept by Mr Thomas Weir …’ (Chambers, 1825, p. 255) The entryway and Thomas Weir’s flat above are highlighted.

Photograph by Francis Chrystal, 1903 (© City of Edinburgh Council – Edinburgh Libraries Capital Collections)**.

Plate 13.1 (b) : Milne’s Court interior view

From the entrance in (a) it is down a descending passageway and a flight of stairs to the court itself. The first floor above street level is therefore the second floor when viewed from the court, so that Chamber’s description does not quite pin down the location of Dr Thomas Weir’s shop. Photograph by Alexander Inglis showing the court in a dilapidated state, as it was in 1870 (© City of Edinburgh Council – Edinburgh Libraries Capital Collections)**.

See CANMORE: ID 277010 and Wallace (1987, pp. 26−27).

From Thomas Weir, the recipe and rights went in 1711 to his widow (implying that Dr Weir had married a second time) and from her they went in 1715 to his son Alexander, followed in 1726 by his sister Lilias (namesake of Dr Anderson’s daughter Lilias, who was probably her grandmother). But, of course, Dr Weir had another daughter, Sarah, who it was that had married the first George Irving of Newton, and so it turned out to be George and Sarah’s youngest son, Dr Thomas Irving (c.1725−c.1804) who, in 1770, eventually inherited the recipe and rights from his Aunt Lilias. It was Thomas’ elder brother who became the second George Irving of Newton, and great-grandfather of James Clerk Maxwell[5].

In August 1747, Dr Thomas Irving was appointed as surgeon to the 14th Regiment Hamilton’s Dragoons serving in Ireland. Until his return to Edinburgh in October 1774, he was based mainly at Lisburn, in the north (Hamilton, 1901, p. 18; Grant, 1944, p. 110 [see under ‘Irving, Alexander’]).

By 1774, not only were Dr Thomas Irving and his wife Jean Chancellor[6] doing business at the same place in Milne’s Court, they lived at that very same address alongside Thomas’ elder brothers George and his second wife, Mary Chancellor, and their family. At least they seemed to have had reasonable accommodation, for when the house was put up for sale nearly a century later it was described as comprising seven rooms plus a garret and a cellar.

The pills must have been very successful, for not only was there strong competition, the pills were also being sold much further afield. The Cumberland Chronicle (1777) advertised:

Doctor Anderson’s Pills (made by Thomas Irving, surgeon of Edinburgh) are sold in Whitehaven by J. Dunn, the printer of this paper.

If that is at all surprising, by the middle of the eighteenth century the pills were even considered to be one of the eight essential medicines for use within the American colonies (Griffenhagen & Young, 1959, pp. 155, 162). [7]

Wooton (1910) has it that after Thomas Irving died, the secret recipe and rights passed ‘to his widow, Mrs. Irving, 1797’, who would continue to make the ‘only genuine pills’. the Anderson’s Pills advertisement in the Edinburgh Advertiser of 20 July 1798, however, informs us that he died some months earlier in that year. Until about 1805, moreover, the same advertisement was being placed to reaffirm Dr Irving’s very recent death! there was some form of subterfuge; either he was alive and lying very low, e.g. incapacitated, or his widow was trying to keep his close association with the pills going in spite of his death.Jean Irving continued in the pills trade for many years thereafter. The fact that she apparently lived to the grand age of ninety-nine seems to have been a great testament to their efficacy. According to Chambers’, two of her sisters, one of whom must be a reference to Mary Chancellor, also lived into their nineties. However, the story that he was told by Mrs Irving about being a child of four in 1745, argues that her year of birth was about 1741 rather than 1738.

Although it seems that she temporarily gave up the house cum shop at Milne’s Court[8] towards the end of her husband’s rather extended cycle of ‘deaths’, she remained in the pill business through numerous agents who sold the pills both in Edinburgh and beyond. During these years, she probably lived at her son James’ house in Chessel’s Court in the Canongate[9] (Storer & Storer, 1820), which is towards the other end of the Royal Mile (Plate 13.2).

James Irving was then a colonel in the Royal Irish Guards and was mostly away from home until 1822, although he may have been back in Edinburgh often enough to take some part in the pill making business, for Wootton maintains that his mother assigned him the rights in 1814. She was then seventy-six and may have been concerned about the possibility of dying when her son was away from home and the secret then being lost or stolen.

This engraving by Storer was published in 1820, when Mrs Dr Irving was living at Chessels Court, i.e. in one of the houses that enclosed the court. Since 1810, part of Chessel’s Buildings was used as an asylum for the deaf and dumb. The court and buildings have since been restored and are accessed via the archways at 234−238 the Canongate. (from Storer & Storer, 1820).

13.3 Decline and Ruin

After her son returned to Chessel’s Court, Mrs Dr Irving went back to Milne’s Court where she was between 1823 and 1828. Nevertheless, in 1832, by which time she would have been over ninety years old, we find a substantial classified advertisement for her pills was placed in a Glasgow newspaper:

GENUINE ANDERSON’S PILLS, Continue to be prepared as formerly by Mrs. IRVING, Widow of the late Dr. IRVING, the sole proprietor of the Genuine Receipt, and may be had, Wholesale and Retail, at the original house, Milne’s Court, head of the West Bow, Edinburgh, where they have been constantly sold for nearly 150 years. … The public may also be supplied with this Medicine by … most of the respectable Druggists and Medicine Venders throughout Scotland. (The Glasgow Herald, 13th July 1832)

According to this, she was back at Milne’s Court and still very much in business and continuing to supply the pills once more at the age of about ninety, which must have been exploited as a testament to their efficacy. Very similar advertisements had also been running in The Scotsman (1823, 1831, 1834) with an even longer list of druggists and agents selling the pills for her in Edinburgh. Judging by the scale of her advertising and network of agents, it would be quite unlikely that she was doing it all on her own. Nevertheless, bearing in mind what had happened during her husband Dr Irving’s latter years, she probably wanted to make it look as though she was still the one in charge of it, all for the sake of the brand continuity and the ‘secret recipe’.

What also points to this is that Mrs Irving and her son were not the ones actually selling the pills at Milne’s Court. Chambers (1825, p. 256) describes the situation as it was about 1825:

The Pills continue to be sold here … by Mr James Main, Bookseller who is agent for Mrs Irving … Portraits of Anderson and his daughter are preserved in this house : the physician in a Vandyke dress, with a book in his hand; the lady, a precise-looking dame, with a pill in her hand about the size of a walnut, saying a good deal for the stomachs of our ancestors.

Mr Main’s Post Office directory entries for 1827 and 1828 concur with this[10]. A possible explanation for his involvement is that by then Mrs Dr Irving’s involvement in the pills may have been on a parallel with Colonel Sanders’ current involvement with fried chicken. By 1829, however, Mr Main had moved to a shop at 52 George Street in the New Town and was no longer mentioned in connection with the pills. Curiously, the advertisements in The Scotsman reveal that a druggist by the name of Gardner had already been dealing with the pills from that same address, and had been doing so since 1823.

Mrs Irving also had the daughter named Bethinia who married her cousin, Alexander Irving of Newton, in 1814 (see §12.2). It seems that the intention had been to call her Bethia, which was not an uncommon name at the time and had been the name of her great-grandmother, Bethia Blackwood the wife of Thomas Weir, but there was a slip of the tongue on the part of the minister who christened her, a thing apparently irrevocable (Irving, 1907, p. 7). Lord Newton’s entry in The Faculty of Advocates in Scotland (Grant, 1944) indicates that Bethinia was born in Lisburn, just outside Belfast. We can be sure that Bethinia was indeed born in Ireland because that is also recorded against her entry in the 1841 census. From that same source we have her year of birth as being about 1780[11]. As previously mentioned, in 1747 her father Dr Thomas Irving was appointed surgeon to the 14th Dragoons stationed in the vicinity of Belfast, but returned to Scotland in 1774 and was back at Milne’s Court by 1775. About ten years later there was a period of absence, for he was not listed there between 1784 (the next available directory year) and 1789. This implies Dr Irving was back in Ireland with his wife around 1780. Indeed, we find later that he claimed to have been physician to the County of Antrim Hospital (Edinburgh Advertiser, 1798), a civilian appointment that he may have taken up in the hope of settling down there. However, we find that from 1786 ‘Mrs Dr Irving’, at least, was back again in the Canongate[12], not far from Chessel’s Court.

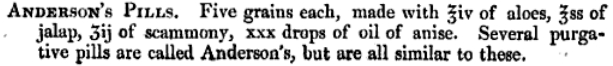

Mrs Irving seems to have lived out the rest of her years with her son Colonel James Irving and his family, first at Chessel’s Court in the Canongate and then in the New Town at 8 West Maitland Street where she died in 1837. Our story, however, is not yet complete because an advertisement in The Scotsman of 22 September 1838 informed the public that her son, named only as ‘Mr Irving’, was now making the pills from the same, original, secret recipe, notwithstanding the fact that the basic recipe of all the competing brands had by then been openly published in a current pharmacopoeia (Rennie, 1837, p. 27):

One might have thought that as a senior military man James would not deign to dabble in the manufacturing and selling of the pills himself, rather he would have employed someone else to do it for him. Instead, he carried on the family tradition of making and selling them just as before, keeping Milne’s court as the focus of the business and remembering to advertise that they were still ‘just as his mother used to make them’, and at the same time thinking it better to refer to himself as plain Mr Irving rather than by his military title of Colonel[13]. Now considering Mrs Irving’s great age, one would not expect her son to outlive her by long, and given that his final entry in the Edinburgh directory was 1841, we could guess at this being around the year of his death, but this was not so.

The story as revealed almost twenty years later is entirely different (The Scotsman, 1860). ‘Mr Irving’ was making £400 a year from the pills when he took over making them, a substantial income at the time and more than three times his full-pay army pension, but he soon got into debt. The business was by then in decline; there were many competitors and his only remaining advantage was the historic family brand. Furthermore, he had let things slip; the way of selling had not changed[14]. To add to his woes, there had been family troubles even before his mother had died. He complained that his cousin cum brother-in-law Alexander Irving, now the judge Lord Newton, had practically removed him from his house at Chessel’s Court, probably in the latter half of 1831, and put him and his elderly mother into a rented flat at West Maitland Street in the New Town.[15] It may well have been a problem concerning a debt, or a disputed family inheritance, which Lord Newton wanted to sort out while he was still able[16] to do so.

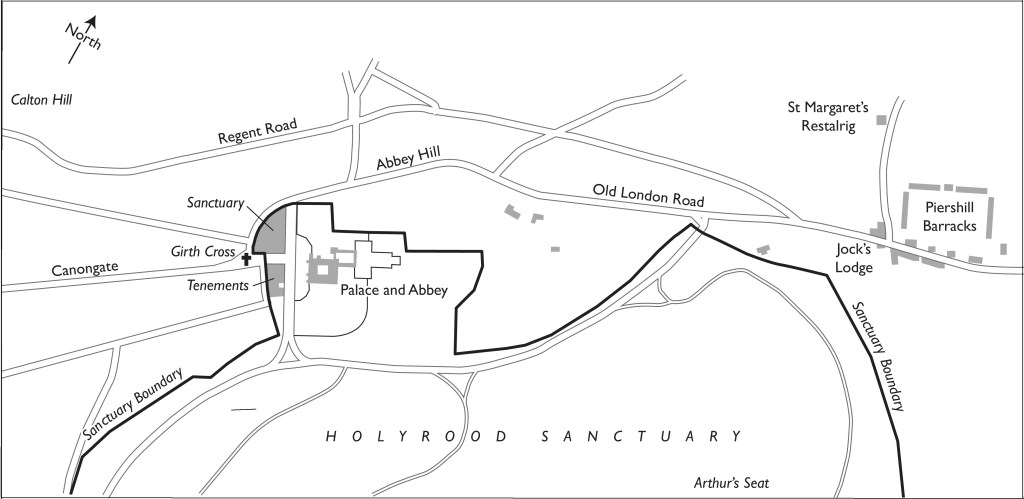

Debt indeed seems to have been the likely problem, for about the time of his mother’s death, and certainly before 1840, James Irving had to set up a trust administered for the benefit of his creditors by an accountant. He blamed Lord Newton once again for his woes by saying that they all started when he had to leave Chessel’s Court, and in particular Lord Newton had promised to pay his rent in return for getting him out, but then had gone and died. His new rent was £130 a year all told, quite a considerable sum given his net army pension was £120, and so he was dependent on the pill business to cover the difference plus all his other expenses. By the year his mother died, he had found it expedient to quit West Maitland Street and by 1839 he had moved far to the opposite side of the town to Wheatfield, a farm house just beyond the cavalry barracks at Piershill (Wallace, 1987, p. 111). It would not have been very convenient for the pill business at Milne’s Court but rather more convenient for the Abbey debtors’ sanctuary (Figure 13.1), where it would have been be possible to take cover from his creditors when the need arose. As a retired senior officer fallen on hard times, perhaps he was able to find some sort of employment at the barracks. In the end, however, he remained listed at Wheatfield for only three years, after which any further trace of his whereabouts evaporates.

Wheatfield is off the map just to the east of the barracks

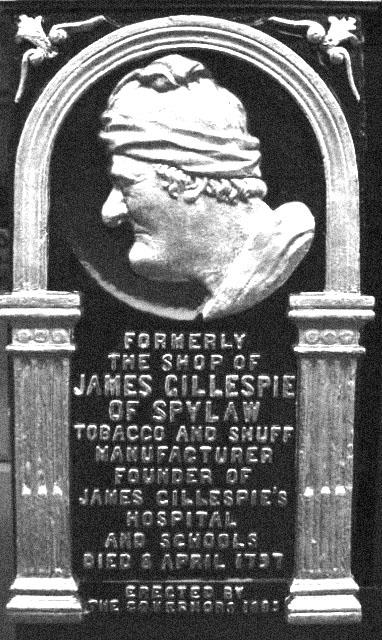

From then on, things only worsened; the pill business was still going downhill and so, ironically, the now General Irving felt the need to change his agent, which he did about 1850. He appointed a Mr Cotton (possibly George) who had a shop at number 231 on the High Street, which had previously been owned by the Edinburgh tobacco magnates James and John Gillespie of Spylaw[17]. It is now marked by a commemorative plaque bearing James’ image in bas-relief (Edinburgh Museums, 2013).

The memorial plaque to James Gillespie of Spylaw at 231 the High Street, presently the site of a bistro. A few years after James’ death’ the shop was in the hands of George Cotton, who had it from 1806−1878 (Edinburgh Museums, 2013).

Mr Cotton does not seem to have taken the pill business as seriously as General Irving would have liked, for the general claimed to have got little money back from him over the next ten years. In fact, he suggested that Mr Cotton was cheating him by selling instead his own counterfeit version of the medicine. Whatever the truth of the matter, the lack of any substantial income eventually left him with debts amounting to nearly £3,300, an enormous sum that could have purchased a very substantial house. His creditors therefore took action, leaving Irving in very straitened circumstances.

The secret recipe, however, was being held under lock and key by a Mr Gibson, accountant to his creditors’ trust. Strangely, Gibson did not offer it up to the creditors, perhaps because he knew it to be worthless, being no different from what had already been published in the pharmacopoeia and therefore better off being kept ‘secret’. Despite Irving’s difficulties, there is no evidence to suggest that the pills themselves had waned in popularity, the real problem was that the number of sources of them was increasing, all claiming to be the genuine article. In the end, realising that Irving would never clear his debts, his creditors sued for bankruptcy [18].

During the bankruptcy hearing, General Irving again maintained that he could set things right by getting back the wherewithal to merchandise the pills and starting anew, but by now he was severely deaf and nearly blind, and so the court did not press him further . In 1863, however, things came to a resolution with both the rights to manufacture the pills and the house at Milne’s Court being put up for auction at Dowell and Lyons in George Street. Meanwhile, a few days before the auction, someone placed a notice in The Scotsman claiming that the recipe for the true Anderson’s pills was ‘worth so much waste paper’ (The Scotsman, 1863, p.1).

Whatever the outcome of the auction was, General Irving survived only to the following February, dying in a flat in William Street in the New Town ‘from old age and reduced circumstances’. His death was reported by his son George, who lived in Portobello[19]. Clearly he had not done much to help his father in his difficulties, nor had his sister Bethinia, Lord Newton’s widow.

13.4 Survival

Returning to the question of others having got into the Anderson’s pills market for themselves, Raimes, Blanchards & Co., predecessor of the Edinburgh pharmaceutical company Raimes and Clark, were by 1842 manufacturing and selling copies of the pills, supposedly under licence (but from whom?). However, they eventually bought out the rights, such as they were, in 1876 in order to reduce costs in the face of the competition (Cumming & Vereker, c. 2008). Wootton (1910) confirms this date, and informs us that it was then a Mr J. Rodger who sold them, and so perhaps it was he who had picked them up about twelve years previously, when they were auctioned.

Raimes and Clark were still making the pills in small quantities well into the First World War period, and one source mentions that they could be had in some places as late as 1956 (Ellis, 1956). Contrary to Chambers’ description of the pills based on Anderson’s portrait, however, the information held by Lindsay & Gilmour, the present owners of the archived materials, shows that the pills are black and more the size of a pea than a walnut, and so Chambers appears to have confused the pill-box for the pill itself! Also in the archive are some of the pills, their authentic packaging, trademarks and early sales literature, examples of which are shown in Plates 13.4 (a)−(d) (Cumming & Vereker, c. 2008).

Plates 13.4 (a)–(d) : Anderson’s Pills (Courtesy Raimes Clark).

Notes

** www.capitalcollections.org.uk

[1] Miles Irving (1907) suggests that Bethia Blackwoods’ father was Sir Robert Blackwood Bt. of Petreavie near Dunfermline. This needs some clarification, for this baronetcy was in the Wardlaw family, who retained it until the twentieth century (Rayment, 2008). Sir Robert Blackwood ( fl. 1648−1716) took the appellation ‘of Pitreavie’ in 1711 on purchasing Pitreavie Castle from the successors of the Wardlaws of Pitreavie. His knighthood, however, was bestowed during his time as Lord Provost of Edinburgh (1711−13), and so it is likely to have been received as a result of holding that office. Secondly, from comparing the entries for Robert Blackwood in SCRAN (2013) and Paterson (1847, p. 202), it seems that each source has only part of the story correct. Piecing them together, however, we may surmise that there were probably three overlapping generations of Robert Blackwood. If the dates are correct, Paterson’s Robert Blackwood who died in 1711 must actually be the father or uncle of the Robert Blackwood that was Provost of Edinburgh. The third generation Robert Blackwood is the Provost’s eldest son, as given in the latter part of the SCRAN record (despite it being previously stated that there were only two sons and that they were named John and Alexander). We may guess that there were other siblings in this generation, one of whom was our Bethia Blackwood. Paterson also informs us in the footnote that the Blackwoods of Pitreave were descended from the Blackwoods of Ayr, and therefore not directly connected to the village of Blackwood, from whence came the Weirs of that ilk.

[2] Wootton (1910), however, seems to have had access to the information they contained, at some point.

[3] Who his father was is not mentioned in any of the sources, and so what connection he may have had to other Weirs in our story is unknown.

[4] The only particulars that identify Thomas Weir in this document are those given for his address, which are to be found in the footnote:

…Thomas Weir Chirurgeon at his Dwelling-Houfe in Edinburgh, on the South fide of the High-Street of the fame, at the Stone Land, and Third Door of the Fore-Turnpike [front stairs] thereof, [at] the upper well or Conduit, commonly called the Cable-Well, a little below the Weigh-Houfe of Edinburgh.

The Weigh-House was at the top of the West Bow and the nearest well below to the east is visible on several city plans including that of William Edgar, 1742. This places Dr Weir’s house between Johnson’s Close and Riddle’s Close, just across the street from the better known James’ Court. As can be seen on the 1850’s large scale OS map, the courtyard of Dr Weir’s house was readily accessible from the foot of Johnson’s close, perhaps only a matter of 40 paces or so.

[5] Robert, the eldest son, had died relatively young and so Newton itself went to the middle son, the second George Irving. This George’s first wife was Isabella Colquhoun, but she died early and their only surviving child had been a daughter, Janet Irving, the grandmother of James Clerk Maxwell. Following Isabella’s death, George married Mary Chancellor of the Shieldhill family in 1763.

[6] Sometimes referred to as Jane, she was the sister of Mary Chancellor.

[7] Griffenhagen & Young (2009, pp. 155, 162) give the following:

In 1824 there issued from the press in Philadelphia a 12-page pamphlet bearing the title, ‘Formulae for the preparation of eight patent medicines, adopted by the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. . .. all eight of these patent medicines … were of English origin…Hooper’s Female Pills, Anderson’s Scots Pills… George Gilmer advised customers that …he could furnish, at his old shop near the Governor’s, Bateman’s Drops, Squires Elixir, Anderson’s Pills. [Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, 27 May 1737]

‘Scots Pills were not cited for sale in the pages of the Boston News-Letter until August 23, 1750. ‘Thomas Preston, for example, announced to residents of Philadelphia in 1768 that he had just received a supply of Anderson’s Pills [Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, 1 December 1768].[8] In 1804 (EPD)

[9] Although the name now refers to bottom section of the Royal Mile that runs from the top of St Mary’s Street down to Holyrood, the Canongate was then a separate burgh beyond the city wall. The entry for ‘Mrs Irving’ at Chessel’s Court could have been either for Colonel Irving’s wife, Charlotte Irving, or for his mother, Jean Irving. Only when the entry is stated as ‘Mrs Dr Irving’ can we be completely clear that it refers to the latter.

[10] According to the Edinburgh Post Office (PO) directories of the time, the bookseller James Main had his shop at 14 West Bow, the zig-zag street that dropped steeply from the top of the Lawnmarket, just facing Milne’s Court. His earliest record there is for 1804, and in 1825 he also lists his house as being in Milne’s Court. But if he was dealing in them in 1825, there was a hiatus in 1826 when he is listed as ‘late bookseller’, that is to say, he had retired from the book business, and if he was still selling the pills he would surely have amended his listing to say so. The following year, however, he was back in business (or possibly a son had taken it over) but this time round he also advertised that he was an agent for the pills. In EPD (1827 and 1828) his directory entry is:

[Main] James, Bookseller, and agent for genuine Anderson’s pills, Milne’s court

By 1829, however, he had moved to a shop in the New Town, at 52 George Street, and although he remained in the bookselling business for another eight years, his name was no longer mentioned in connection with the pills.

[11] It appears that many of the ages given were mere estimates, for they often seem to be multiples of five. Women are notoriously under-estimators when it comes to their age.

[12] At Sommerveile Close

[13] At this time senior army officers were promoted on the basis of seniority and this continued even after they retired. He was made Lt. General in 1854 (London Gazette, 1854) and he eventually ended up as a full general, as did his brother George.

[14] Corley (2004) tells us ‘by the early nineteenth century [the portraits of [Dr] Anderson and his daughter Katharine] were in poor condition and later disappeared’

[15] They were listed at Chessels Court in that year but in the year following. Furthermore, Lord Newton died in March 1832 after period of severe illness (Brunton & Haig, 1832, p. 552 (Senators &c)).

[16] In 1828 John Irving WS assigned a fire insurance policy on a ‘third storey flat in Milne’s Court in Edinburgh’ to John Clerk Maxwell (DGA: GGD56/35/10A, 18/2/1858). Since John Clerk Maxwell had inherited his mother Janet Irving’s property, it is likely that this included an interest in one of the flats in Milne’s Court where the Irvings lived. Since Janet’s father was listed as living at Milne’s Court in 1775, it may be that he had left one of the properties there to his daughter.

[17] James and John Gillespie of Spylaw, in Colinton just outside Edinburgh, became famous as tobacconists and, particularly James, as philanthropists. John ran their shop in the town at 231 the High Street while James, his elder brother and senior partner, ran their snuff mill on the Water of Leith, just at the back of their house. Despite his wealth, James was a very kindly and modest man. The one extravagance he allowed himself was a rather plain looking carriage, at which Henry Erskine (q.v.) poked fun:

Wha wad ha’e thocht it,

that noses had bocht it?

When James died, he bequeathed his fortune to the setting up of a school and a hospital* on Bruntsfield Links (Kay & Paton, 1877, vol. 2, pp. 218−222, No CCXLIV). A modern school still bears his name.

George Cotton had a tobacconist’s shop in Edinburgh from the 1780’s, and by 1850 he and his family had several shops between them, including: George Cotton and Sons, tobacconists to the Royal Household, 23 Princes Street; John Cotton, snuff maker, 35 Princes St; George Cotton, tobacconist, 231 the High St, and James Cotton, tobacco manufacturer, also at 231 the High St. George Cotton took on the latter premises, which had been John and James Gillespie’s old shop, from about 1806 (EPD). Cotton’s tobacco blends came to be sold worldwide and even in 2012 a US tobacconist, Chief Catoonah Tobacconists of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was supplying a prize-winning ‘Princes Street Mixture’

* The term as then used referred to a refuge for the needy, e.g., as in orphan’s hospital.

[18] At this point the creditors appointed a different accountant, James Latta, who was one of the trustees. A minor coincidence was that Mr Latta’s offices were in India Street, at numbers 32, and 30-A

[19] His house in Bath Street was replaced by the old County Cinema, which in turn has been replaced by housing.