Brilliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

If James Clerk Maxwell was the reason for writing this book, it is not so much about the man himself as it is about whence he came. It deals with the origins of his predecessors and of the families, some rich and some brilliant, with whom they were connected. It also gives us a picture of what life might have been like through the generations of any well-to-do Scottish dynastic family. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, it reveals how they lived, or perhaps more accurately, how they managed to survive. If birth was the first great struggle, living beyond infancy was the next. For those who could have children, bringing eighteen of them into the world (at an average rate of about one per year!) was not particularly unusual, nor was it unusual to see half of them dead before they reached adulthood. For those who did survive, life was still uncertain, for they would not escape the visitations of terrible illnesses such as consumption, smallpox and typhoid, for which there were no cures, even for the rich. A simple injury such as a fractured limb could be a death sentence. They would live or die according to their relative strength or weakness, and their luck. Sometimes fate was cruel indeed, for it is not unusual to see burial records noting the death of a parent and several children all within the space of a few weeks.

Property was the traditional basis of wealth. The eldest son of a comfortably-off family could expect to be comfortable indeed. He would be well educated, have fine clothes, eat good food, and entertain himself with art and music. It was expected that he should marry and to that end his wife would be chosen from another respectable family in the hope of enhancing his property. In due time, he would become the new Laird and begin planning a future for his own children. Surprisingly, in Scotland it seemed to be the custom for such men to have a profession, for example, as an advocate. If the Laird had many brothers, we could also expect to find amongst them a solicitor, a doctor, a soldier, a sailor and a minister of religion. His sisters would be gentlewomen, some of whom would be married off onto gentlemen similar to himself, while the others would remain part of his household.

Although such people might have been regarded as being very well-off, this was a relative term. Even with good management, money was frequently in short supply and marrying off sisters and daughters was an expensive business. Likewise, while a Laird generally passed on his property to his eldest son alone, he would hope to create the prospects of property for his second son by finding him a convenient marriage. Sometimes, however, he would also contrive to give him a small parcel of land. As to the others, they usually had to take their chances in the world with little more than a good education, good connections and the good name of their family to help them. There was always the chance of falling heir to some property or other, but otherwise they simply joined the ranks of professional gentlemen one tier below their eldest brother.

For the population at large, in addition to the perpetual scourges of poverty and disease, there were two others, religion and war. The former was entangled with politics and the latter was often the outcome. To belong to a non-conformist religion was to set oneself against the state, for which the consequences could be severe. Non-conformists were harshly repressed, and in the face of such injustice their reactions gave rise to an undercurrent of rebellion, which now and then would come to the surface. But rebellion also presented the opportunity of settling old scores between sides that were mainly defined by history and religious differences.

Our story unfolds during the religious and political turmoil that spanned most of the seventeenth century, thence through the Union of the Scottish and English Parliaments and two Jacobite uprisings, after which came the relative tranquillity that engendered an age of enlightenment. Scotland had long been overshadowed by its larger neighbour, England, which was much richer and, by ruling the seas, dominated wealth-producing foreign trade. Much of Scotland, namely the Highlands to the north and the islands to the west, were even in the seventeenth century largely untamed and were ruled along old feudal lines by independent, fractious chieftains whom the Lords of the realm struggled to keep at peace. Only after the last Jacobite rising of 1745 did things really begin to change. For those dwelling in the south and on the east coast, apart from the fact that they were generally poorer, life was much more like that of their English cousins. Nevertheless, there seems to have been a certain drive amongst the Scots to work hard in the face of their perpetual struggles and to do better, and by one small achievement after another, they began to improve. There were of course failures along the way, but they did in the end succeed, for within a century the social landscape was transformed from one of relative poverty and instability to one of greatness and splendour. They had created an era that has been justly called the Scottish Enlightenment, in which Scots seemed to come to the forefront in everything. Indeed, they succeeded not only at home, but in London, Europe, and such far-flung places (as they truly were at the time) as Russia, India and America.

Given that the population of Scotland was small, and that the number of those who were well enough off to be able to play some part in this enlightenment was smaller still, it is amazing to see how many ‘giants’ were thrust onto the stage in the arts, sciences and humanities to play some vital part that will never be forgotten. Nor did the Scots neglect business, exploration, medicine, engineering and architecture, where they also left lasting legacies. In architecture, in particular, this can be seen in the form of stately houses and public buildings all around Great Britain, but no greater concentration of them will be seen than in Edinburgh’s New Town, which was at the very heart of that period of enlightenment.

James Clerk Maxwell was just one of the great men thrown up by the Scottish enlightenment. Much has already been written about his life and works (see bibliography) and so here we give a mere sketch of them to set him in his proper place in our story which spans the lives and deeds of the Clerks, the Maxwells and Clerk Maxwells, the Cays, the Wedderburns and the Mackenzies, who were all part of his family network. It also touches on his two close school friends, Peter Guthrie Tait and Lewis Campbell, with the connection between all of them being Edinburgh’s New Town, or more precisely, Edinburgh’s Second New Town, which began about 1800, just a third of a century after the start of James Craig’s original New Town of 1767 (Youngson, 1966). To provide some orientation for the reader unfamiliar with Edinburgh, Figure 1.1 shows the layout of the original Old Town of Edinburgh, together with these two consecutive new town developments to the north, and an earlier one to the south.

The connection with the Second New Town in particular comes about because at some time or another, between roughly 1800 and 1865, that is where most of these families lived; some for nearly all of that time, others, like Maxwell[1] himself, for just a few years. Irrespective of how long, they were all indelibly products of Edinburgh’s New Towns and all that went with them. By tracing where they lived we bring new light to their family history and to the Clerk Maxwell connection with 14 India Street, which was Maxwell’s birthplace, and 31 Heriot Row, where he lived during term-time from 1841 until 1850. The locations of these key addresses, and many more that we will encounter, are indicated in Figure 1.2.

In order to understand something of the reason why Edinburgh proved to be such a fertile breeding ground for men like Maxwell, the circumstances behind it need some explanation. The growing atmosphere of peace and prosperity that began in the middle of the eighteenth century seemed to open doors for men of enterprise and genius to come to the fore, particularly in Edinburgh.

The Old Town spills down both sides a sloping ridge, the ‘Royal Mile’ that extends from Castle Rock at its western apex to Holyrood Palace on the east. The valley to the north of this ridge, now Princes Street Gardens, had been flooded in bygone times to form a defensive moat called the Nor’ Loch (Daiches, 1986). George Street lies along the line of a second flatter ridge to the north of this valley, and from there the ground slopes gently downhill northwards to the sea, the Firth of Forth. To the south of the Old Town, however, was the Burgh Loch, which had been progressively drained to make meadows. Around 1760, the burgesses looked to these sites on the north and south for the expansion of the town. Although the New Town refers to the planned development to the north that commenced in 1767, the small development around George Square at the edge of the Meadows started in the previous year. Within just thirty years, the mid-grey area (first New Town) was almost fully built and a second New Town was called for. Building began in the light-grey area (second New Town) about 1800, but another thirty years saw that largely built up too. Today, the New Town refers to the entire development characterised by buildings of quality executed in a harmonized Georgian style and set amongst wide streets and numerous gardens.

Also shown are the houses where Lewis Campbell (27 HR), Alexander Graham Bell (16 SCS), Sir Walter Scott (39 NCS), Robert Louis Stevenson (17 HR) and Henry Mackenzie (6 HR) lived.

Key:

AP: Ainslie Place; CS: Charlotte Square; GS: George Street; GSS: Great Stuart Street.

HR: Heriot Row; IS: India Street; MP: Moray Place; NCS: North Castle Street;

NS: Northumberland Street; PP: Picardy Place; RI: Royal Institution; RS: Rutland Street; SCS: South Charlotte Street; SEC: SE Circus Place; SSQ: Shakespeare Square

Despite the Scottish Parliament itself having been dissolved in 1707, Edinburgh was still the Scottish capital and the legal, financial and commercial centre of the nation. It was home to the cream of the nation: landed gentry; judges, lawyers and politicians; bankers and businessmen; doctors, scientists, engineers and philosophers; artists, architects, writers and poets, many of whom were both willing and able to reach for the top. There began an outpouring of ideas, initiatives and progress.

Although these circumstances created the motherlode of this progress, what is hard to explain is how, at a time when the population of the capital was still less than 100,000, there were enough such men to produce the end result. Moreover, we can only speculate that it was the breaking free of the intellectual and financial fetters of the past that provided the catalyst that sparked the yield of so many remarkable people. Remarkable also, in that they reached the highest rank, not just at home, but on the world stage. A few of the better known of them are David Hume (philosopher), Adam Smith (economist), James Hutton (geologist), James Boswell (diarist and biographer of Johnston), Robert Adam (architect), Walter Scott (novelist) and Henry Raeburn (portrait painter), but there were many others who are better known by their contributions, for example, William Smellie, the founding editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

In the early enlightenment, the youth of the upper classes not only travelled in Europe but were frequently educated in Europe; for example, James Boswell studied Law at Utrecht before engaging on his ‘grand tour’, all of which he recorded for us in his journals. When they came into their fortunes, these young men already had aspirations, and compared with what they had seen on their travels, Scotland had a lot of catching up to do. In order to achieve their desire to progress, they could rely on a network of family and friends who were ready and willing to join in on the act. Marriages between families, and even within families, were a way of consolidating wealth, in particular heritable property. Marriage contracts afforded the means of securing these things in much the same way as merger contracts between businesses do today. In this story we will hardly encounter a person with a middle name that is not the surname of a connected family, and the Clerk in James Clerk Maxwell is no exception[2].

The well-to-do families of Edinburgh counted numerous lawyers amongst them who had the means and the power to bring such things about, and when it was necessary they had the wherewithal to obtain the force of law and the occasional act of parliament. So it was that over several generations, the lands of a Maxwell in Dumfriesshire and of a Clerk in Midlothian were brought together into one family. Dorothea Clerk was heiress to the Maxwell estate of Middlebie[3]. In 1735 she married George Clerk, her first cousin and second son of the 2nd Baronet of Penicuik, with the eventual settlement bringing to him the Clerk lands of Dumcrieff, near Moffat, as well as the right of Middlebie. George Clerk of Dumcrieff, or George Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, as he then alternatively styled himself, got into financial difficulties as a result of being too ‘deeply interested in promoting the commerce and industries of his native land’(Wilson, 1891) and in order to pay off his creditors he had to sell off both Dumcrieff and the part of the Middlebie estate that included Middlebie itself. In due course, however, he inherited the Penicuik baronetcy from his brother to become Sir George Clerk, 4th Baronet of Penicuik; the baronetcy was his for just one scant year before passing to his eldest son John in 1784.

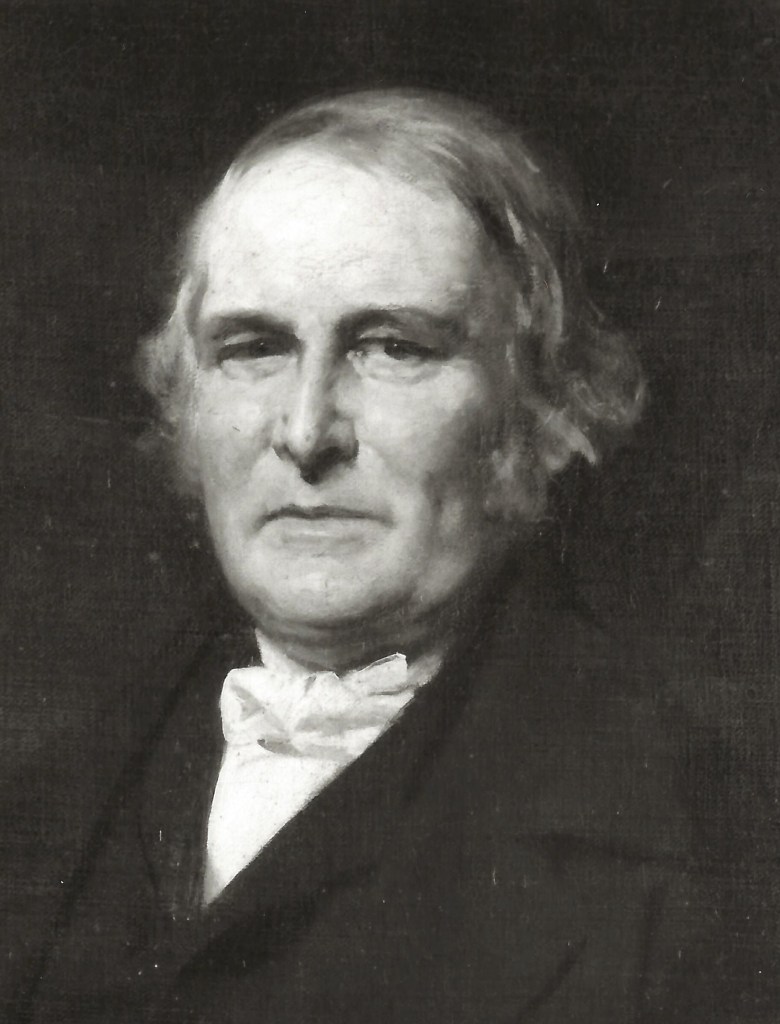

James Clerk Maxwell’s father (Plate 1) was baptised as plain John Clerk. He was the grandson of this Sir George Clerk, or Clerk Maxwell, but it was John’s older brother, named George after his grandfather, who became the 6th Baronet.[4] However, the entail of the Middlebie estate (see §6.3), required that it be held separately from the baronetcy of Penicuik (and vice versa for Penicuik) and that the holder had to take the surname Maxwell. And so it was arranged that the older brother George should inherit the Penicuik estate together with the baronetcy, while the younger brother, John, should be the one to change his name and inherit the Middlebie estate. In 1808, George Clerk came into his majority as 6th Baronet of Penicuik and similarly by 1811 his brother had officially become John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, the 7th of his line (Family Tree 2).

Plate 1 .1 : John Clerk Maxwell aged Sixty Three

In a letter of 5 March 1854 John Clerk Maxwell wrote to his son: ‘Aunt Jane stirred me up to sit for my picture, as she said you wished for it and were entitled to ask for it, ‘qua’ wrangler. I have had four sittings to Sir John Watson Gordon, and it is now far advanced; I think it is very like … It is kit-cat size, to be a companion to Dyce’s picture of your mother and self, which Aunt Jane says she is to leave to you.’ (C&G, p. 207). He was therefore sixty-three at the time, not sixty-six as given earlier in C&G (facing p. 11).

By courtesy of Sir Robert Clerk of Penicuik

George and John took part in the age of enlightenment in their own different ways. George had a busy and distinguished political career, rising to Cabinet rank in several different government posts and becoming master of the Royal Mint, yet in spite of this he had the time and interest to become President of the Royal Zoological Society. John settled for being an advocate, but was also an enthusiast of science and technology, the rapid advances of which held a particular fascination for him, which in due course he sought to pass on to his son, James. If he held any ambition at all for a high-flying career, he did not show it, rather his aspirations were closer to home: his family and his small estate. In 1826 he had married the ‘girl along the street’, Frances Cay, who was from a family background not dissimilar to his own. Her mother was a talented portrait artist, her father had property and was also a judge, one brother was a sheriff, another a merchant, while the third was yet another lawyer.

It was through the influence of his wife that John Clerk Maxwell was motivated to shake off his inertia and do something. He therefore forsook the life of a city lawyer and concentrated on a part of his estate called Nether Corsock, in Kirkcudbrightshire,[5] where he decided to build a decent house and become a farmer. The rest of the Middlebie estate brought him a reasonable income, and so, ever cautious and ‘judicious’, he must have realised that there was no great risk involved. Nevertheless, he did not lack the inclination to apply himself and so the project proved a success; his real tendencies were to the practical, and the land suited better than the law.

Until fairly modern times, the lives of the gentler classes were generally divided between spending the summer months at their country seats and overwintering in their town houses. The courts, schools and universities all ran roughly from November to June, with some breaks in between. Once the Clerk Maxwells were ensconced at Nether Corsock, they too would return to Edinburgh, a journey of two days, for the worst of the winter season when nothing could be done on the land. But in the early months of 1831, when Frances must have known she was pregnant, the clear decision was that she should remain in Edinburgh for the birth of the child. And so it was into a genteel but modest family that James was born on 13 June 1831[6], not on his father’s estate but in the Clerk Maxwells’ town house at 14 India Street[7] in Edinburgh’s Second New Town. This was to be James’ principal home for the next two years, until it was at last considered that he was thriving, and that the house that John Clerk Maxwell had been building at Nether Corsock was now fit to be taken over as their permanent family home.

So began the era of James Clerk Maxwell. We shall follow the connections back to his roots, a mere hint of which we have mentioned above in the coming together of the name Clerk Maxwell. And from the roots we shall follow back the branches, to the families connected with the Clerks and the Maxwells, families that brimmed with enterprise and took their own places in the Scottish enlightenment alongside the best of them. They include:

- Sir John Clerk, 2nd Baronet of Penicuik (1676−1755) antiquarian and writer;

- Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) poet;James Stirling (1692–1770) mathematician and lead mine manager;

- Adam Smith (1723–1790) author of The Wealth of Nations;

- Sir George Clerk Maxwell, 4th Baronet of Penicuik (1715−1784) entrepreneur and improver;

- James Hutton (1726–1797) founder of modern geology;

- William Adam (1689–1748) architect and father of Robert and John Adam;

- Robert Adam (1728–1792) neo-classical architect;

- John Clerk of Eldin (1728–1812) artist and naval tactician;

- Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) romantic novelist and historian;

- William Dyce (1806–1864) artist and scholar;

- James D. Forbes (1809–1868) glaciologist;

- William Thomson (1812–1897), Lord Kelvin, physicist and engineer;

- Jemima Blackburn (1823−1909), née Wedderburn, water colourist;

- Peter Guthrie Tait (1831–1901) mathematician and natural philosopher;

- James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) physicist;William Dyce Cay (1838–1925) civil engineer.

It will be noted that four of the names above have already been cited as leading lights of the Scottish Enlightenment. The name of James Clerk Maxwell, however, has never been ranked beside the likes of Hume and Smith. Considering what he achieved, this raises awkward questions about the nature of fame, and about whom the population at large chooses to celebrate or ignore. We will therefore give him his day by beginning with his story.

Notes

[1] Repeating James Clerk Maxwell in full becomes tedious. In any formal setting, his first biographer Lewis Campbell referred to him as Maxwell, which is still the general custom today. Clerk Maxwell seems never to have been in vogue. In less formal situations, however, Campbell referred to him as James, and we will follow his lead in this.

[2] Hyphenated surnames were not common in Scotland at this time. Other examples are Hay Mackenzie and Scott Moncrieff. Andrew Wedderburn Maxwell, Maxwell’s successor as laird of Middlebie, did eventually add the hyphen.

[3] Although Middlebie itself was a small town to the east of Dumfries, the estate consisted of various parcels of land and property scattered about Dumfries. While Dorothea was to become the proprietor of the estate, her guardian or husband would control it ‘by right’.

[4] Following the death in 1798 of his uncle Sir John Clerk, 5th Baronet, who died childless.

[5] The old county also referred to as the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright. It forms the central part of present day Dumfries and Galloway, with Dumfriesshire to the east, Wigtownshire to the west, the Solway Firth to the south, and Ayrshire to the north.

[6] SOPR: Births, 685/01 0560 0296, Edinburgh.

[7] The house is now kept as a museum cared for by the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation, https://www.clerkmaxwellfoundation.org , registered Scottish Charity SC 015003.