Brilliant Lives

by John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

2 James Clerk Maxwell’s Life

and Contribution to Science

You will sometimes hear it said that James Clerk Maxwell is one of the greatest physicists that ever lived. For many people this will be a surprise, for in comparison with Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking, he is practically unknown amongst the general public. This is most keenly demonstrated by an anecdote related by R. V. Jones (1973, p. 67) [1], who was some years ago the Professor of Natural Philosophy at Aberdeen, where a century before Maxwell himself had been the professor (see §2.4). Professor Jones had been told the story of an advertisement that had been placed some years before in the Aberdeen Press and Journal, by a solicitor seeking information on the whereabouts of a certain James Clerk Maxwell. The solicitor dealt with the funds of the local Music Hall, which happened to pay out a small annual dividend to its subscribers, one of whom had been Maxwell. Unfortunately, Maxwell’s share of the distribution was now being returned as undeliverable. While it was bad enough that the solicitor had been unaware that James Clerk Maxwell was ‘the most famous man to walk the streets of Aberdeen’, his letters to Maxwell at the University were being returned marked ‘NOT KNOWN’ !

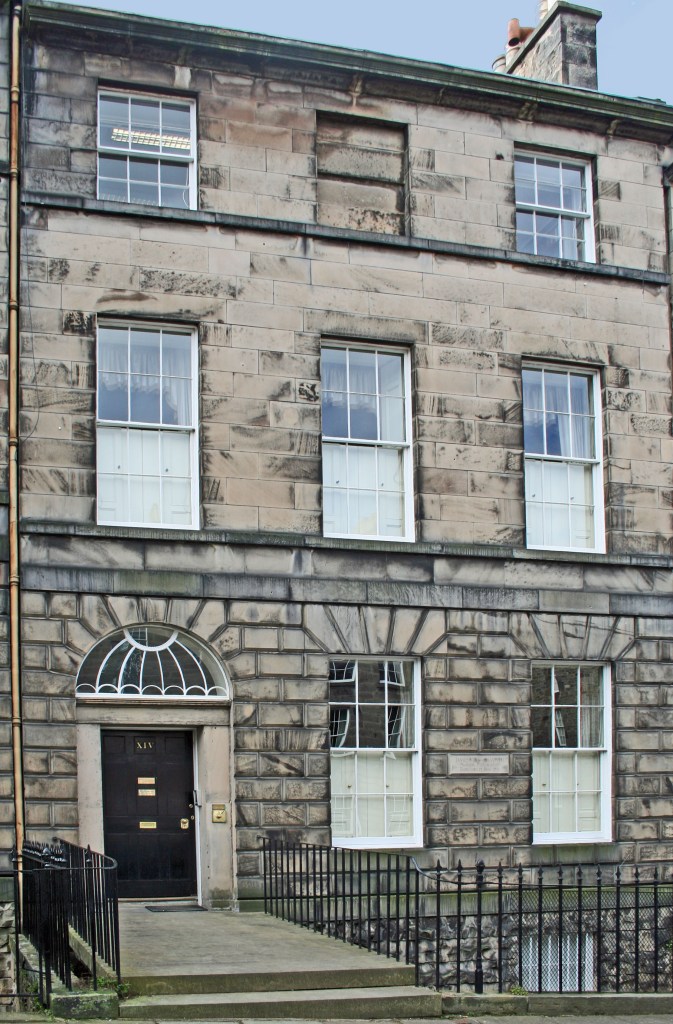

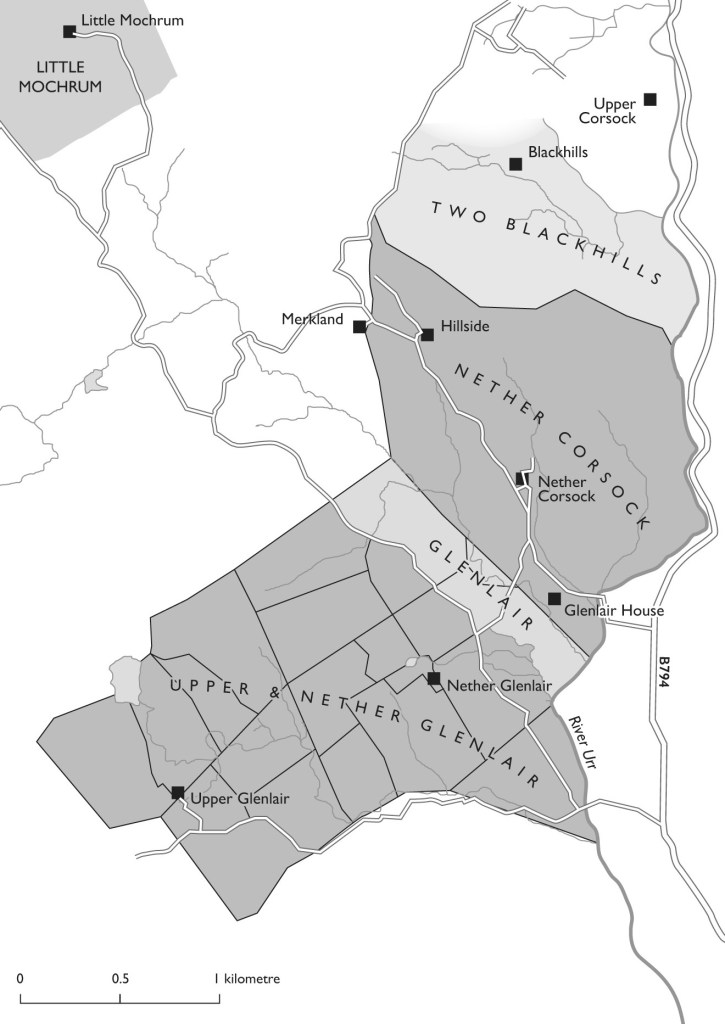

2.1 Behold the Child

Most of what we know about James Clerk Maxwell is to be found in his original biography[2] by Lewis Campbell (see §16.1), a lifelong friend, and William Garnett, who worked alongside Maxwell at the Cavendish Laboratory, first as his demonstrator and then as a lecturer. Although he was born at 14 India Street in Edinburgh (Plate 2.1) and wanted for nothing there, his parents’ lives centred on John Clerk Maxwell’s ‘family seat’ at Nether Corsock a piece of some rough farmland set in a remote area nearly twenty miles west of the county town of Dumfries (Figure 2.1). Nether Corsock was part of the estate that John had inherited from his paternal grandmother, Lady Dorothea Clerk, or Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie. The rest of his estate consisted of a few farms scattered about nearby, and some properties in and near the town of Dumfries, but the farms and properties at Middlebie were long gone by the time he inherited it, sold off in a public roup to pay off his grandfather’s debts. After their marriage, John Clerk Maxwell and his wife Frances resolved to become country gentlefolk, alternating between living at Nether Corsock from spring to autumn and overwintering in Edinburgh beside their friends and family. For the well-to-do this was in any case the general pattern of life; in the Clerk Maxwell’s case the only difference was that John’s business focus was no longer in Edinburgh. The journey back and forth, nearly 100 miles over rough roads and tracks, took two entire days by horse and carriage. Such a journey was not to be undertaken on a whim, but for a definite purpose. Life at Nether Corsock, however, was not ready made for them. They had first to turn rough pasture into a viable farm, and they had no more than a gardener’s cottage to live in. A proper house had to be designed and built, a project that John Clerk Maxwell would have entirely relished, for as a boy he had often dreamed of such things.

For Nether Corsock, see Glenlair.

Amidst all this, in the summer of 1829 Frances fell pregnant. By the time their child Elizabeth was born, they were back in Edinburgh for the winter. Sadly, the child died shortly after birth, and the bereft parents, having married a little late in life, must have wondered if they would ever be lucky enough to have another. Happily, within the space of a year Frances was pregnant again, but since the building of a new two-storey house at Nether Corsock to John’s own design[3] was still then only just about to be started, they decided to stay on in Edinburgh. It seems natural that a man in John Clerk Maxwell’s position would have insisted on his wife staying put in Edinburgh where she could be looked after by nearby family, and the best of doctors. Nothing would be spared, no risks taken. On the other hand, he would have had business to carry on with at Nether Corsock; farmhands and workmen to supervise; and rents to gather in. In the ways of these times, a man decided for himself what had to be done; Frances had to stay and he would just go and get on with things. In any case, what practical use could he be to Frances until it was near the time for the child to be born?

In due course, Frances was safely delivered of a son whom they named James after his paternal grandfather (Family Tree 2) as was then the custom for a firstborn son. Captain James Clerk had died many years before while his son John Clerk was just a child of three; the reason why John came to have a different surname from his father will become clearer later on.

By the time James was two years old and thriving, his parents felt that they could return to Nether Corsock and make it their permanent base. The town house at 14 India Street was rented out and they were never to live there again. The earliest demonstration we have of young James definitely at his new country home is a letter from his parents to Frances’ sister Jane back in Edinburgh:

To Miss CAY, 6 Great Stuart Street, Edinburgh.

Corsock, 25th April 1834.Master James is in great go … He is a very happy man, and has improved much since the weather got moderate; he has great work with doors, locks, keys, etc., and ‘Show me how it doos’ is never out of his mouth. He also investigates the hidden course of streams and bell-wires, the way the water gets from the pond through the wall and … down a drain into [the] Water Orr … As to the bells, they will not rust; he stands sentry in the kitchen, and Mag runs thro’ the house ringing them all by turns, or he rings, and sends Bessy to see and shout to let him know, and he drags papa all over to show him the holes where the wires go through. (C&G, p. 27)

Fortunately, we have an image of James in infancy, with his mother, in their portrait by William Dyce (Plate 2.2), the story of which we will arrive at later. James’ cousin, Jemima Wedderburn, later Mrs Blackburn, was to tell Lewis Campbell (C&G, p. 28) that throughout his childhood his constant question was, ‘What’s the go o’ that? What does it do?’ and he would drill on in this vein until he got an answer that satisfied him. There was not always such an answer to be had, for he could not be satisfied by a mere form of words. His nurse recalled to Campbell (C&G, pp. 30−31) that, having been questioned by James in this manner about the colour of some pebbles he had collected on a walk together, she had answered, ‘That (sand) stone is red; this (whin) stone is blue.’ ‘But how d’ye know it’s blue?’, he retorted.

From Campbell’s own recollection (C&G, p. 28) we hear that James’ earliest memory was of lying on the grass to the front of the house at Nether Corsock ‘looking at the sun, and wondering’. These are Campbell’s italics, for he particularly wanted to impress upon the reader this aspect of James’ character. There would be hardly anything, it seems, that he did not wonder about, and amid all the other opportunities for indulging in some form of play or excitement, he would come to rest, and pause, and simply wonder.

This category-A listed building has changed little since it was built in 1820. The false window on the top floor makes it a little different from some of the other houses in the street.

As well as having a seemingly endless appetite for enquiry, the young boy also had a keen ear for music and a prodigious, highly active memory:

His knowledge of Scripture, from his earliest boyhood, was extraordinarily extensive and minute; and he could give chapter and verse for almost any quotation from the Psalms … These things … occupied his imagination, and sank deeper than anybody knew. (C&G, p. 32)

In most other respects, James was a normal, happy boy. Although born of the landed gentry, his sensible parents did not keep him apart. Nor, as an only child, did they treat him as being overly precious. If there was any local parish school that he could have gone to, however, he did not attend; he was taught by his mother. But there was no haughty separation between masters and servants; in all other things he mixed in with the local boys, for the most part sons of his father’s tenants and workers, taking part in their play and speaking their broad Gallowegian brogue . He had no fear of getting his hands dirty, for he had learned that ‘country dirt’ was ‘clean dirt’ (C&G, p. 34). He rambled in field and wood, climbed trees, took a washtub as a craft to be sailed in the duck-pond, hunted frogs and insects, and by the age of ten he could ride a pony. He was by then in every way a thorough-going country boy.

The single unhappy event that overtook his childhood was the illness and eventual death of his mother. By the time of his eighth birthday it must have been evident that all was not well with her, and in due course she was diagnosed with stomach cancer from which, all efforts to save her having failed, she eventually died at Nether Corsock in December 1839. James must have been all too aware of her suffering, for on being told that his mother was now dead he had declared ‘Oh, I’m so glad! Now she’ll have no more pain’ (C&G, p. 32). Nevertheless, the loss of his mother at such a tender age took its toll and naturally enough disorientated him:

… his activities were apt for the time to take odd shapes … bright and full of innocence as they were … produced an effect of eccentricity on superficial observers … (C&G, pp. 45−46)

A different side of James’ character was to come to the fore in the days that followed, when his father brought in a young, inexperienced tutor to carry on with his education. The two did not hit it off, but whereas it seems that James had hitherto been a fairly rational and obedient boy, now he rebelled. The tutor had somewhat surprisingly found James to be slow at learning, and resorted to employing the sort of rough discipline by which he himself had probably been forced to learn his subjects. James, having been used to the gentle encouragement of his mother, may well have taken it into his head that he was not going to co-operate with such an unworthy interloper. Learning had been part of his daily diet of interesting things that were offered, accepted and taken on board, and now he was not going to buckle down and take it as though it were being thrust at him like some disgusting swill that he must consume or suffer the consequences:

Meanwhile the boy was getting to be more venturesome, and needed to be not driven, but led … his power of provocation must have been … ‘prodigious’. (C&G, p. 41)

Finished by Dyce at Glenlair in the late summer of 1835 when James was aged four.

Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust, licensed under CC0

The tutor’s response was brutal; James was ‘smitten on the head with a ruler’ and had his ‘ears pulled till they bled’. In the tutor’s defence, the maxim then was ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’, and so his methods were not quite so outrageous as they seem today. Nevertheless, James did not run to his father telling tales; he bore it all like a man and soldiered on. This gives us an early indication to another side of the boy’s character, which he was to retain until his last breath; he could patiently endure anything, even suffering.[4] Had not Christ suffered, and his own mother too? James would have learned from his father the traits of the Scottish Presbyterian character; one must be stoical and endure some pain in life, one must be brave and not complain but carry on? One day, however, James decided he had had enough. Whether he ran off from his lesson or would not come in for it, we cannot tell, but we have the scene in Figure 2.2 (C&G, p. 42). We see him in his washtub in the middle of the duck pond, with his tutor struggling to bring him to shore using a rake for a boathook. The standoff has been going on for some time, it seems, for already his father and Aunt Isabella are on the scene awaiting the eventual denouement. His cousin Jemima, the artist who made this record in the late summer or early autumn of 1841, stands on the left; two local lads who possibly shared James’ lessons, watch from the far bank. Only the tutor, however, seems at all perturbed!

the young James and his tutor

Although he did not get to know James until shortly after this episode, according to Campbell his torment at the hands of his tutor, both physical and mental, left him with ‘a certain hesitation of manner and obliquity of reply’, aggravating his slight oddity of character and, undoubtedly, the distress he suffered due to the loss of his mother.

2.2 Edinburgh Academy

On the prompting and advice of his sister-in-law Jane Cay, after the duck pond incident John Clerk Maxwell accepted that his son would be better off going to a proper school. He now recognised that James would need more than the sort of rough and ready education that was to be had anywhere nearby. The loss of his mother was part of the problem, and so it was decided that James should not go to a boarding school; he should go to school in Edinburgh, at the new Edinburgh Academy (Plate 2.3), which was within five minutes’ walk from the care of his two aunts, Jane Cay and Isabella Wedderburn. The former lived in a substantial flat at 6 Great Stuart Street while the latter had a town-house of considerable grandeur at 31 Heriot Row which had been John Clerk Maxwell’s own home before his marriage (Plate 2.4 and Plate 2.5 respectively). There was space enough there for James to have his own room and he would want for nothing; he would have the company of his cousin Jemima and a younger cousin Colin Mackenzie. He would have school-friends in the nearby houses and he could visit his aunt Jane whenever he liked; his father would come up on his usual visits to Edinburgh. And so it was decided.

The school, founded by Lord Cockburn, opened in 1824 about 17 years before James Clerk Maxwell’s first attendance there. Note the unusual oval cupola atop the roof, which James would have seen every day.

That October, Isabella and Jemima travelled down by carriage to Glenlair, as the recently expanded estate and house at Nether Corsock had now become known (Figure 2.3),[5] and there they stayed a few weeks before commencing the return journey, the top of the coach laden with the trunks carrying all that father and son would need during their sojourn in Edinburgh, and to equip James for school (Wedderburn, c. 1841).

Aunt Isabella’s eventual home, 25 Ainslie Place

6 Great Stuart Street is the door on the far left while 25 Ainslie Place is just round the corner on the right. Notice that the dummy windows to the left of the corner help maintain the regularity of the frontage.

Numbers 30 (far left) and 31 (centre) are the centrepieces of the west side of Heriot Row, being the only houses there that were eventually allowed a third floor above ground level.

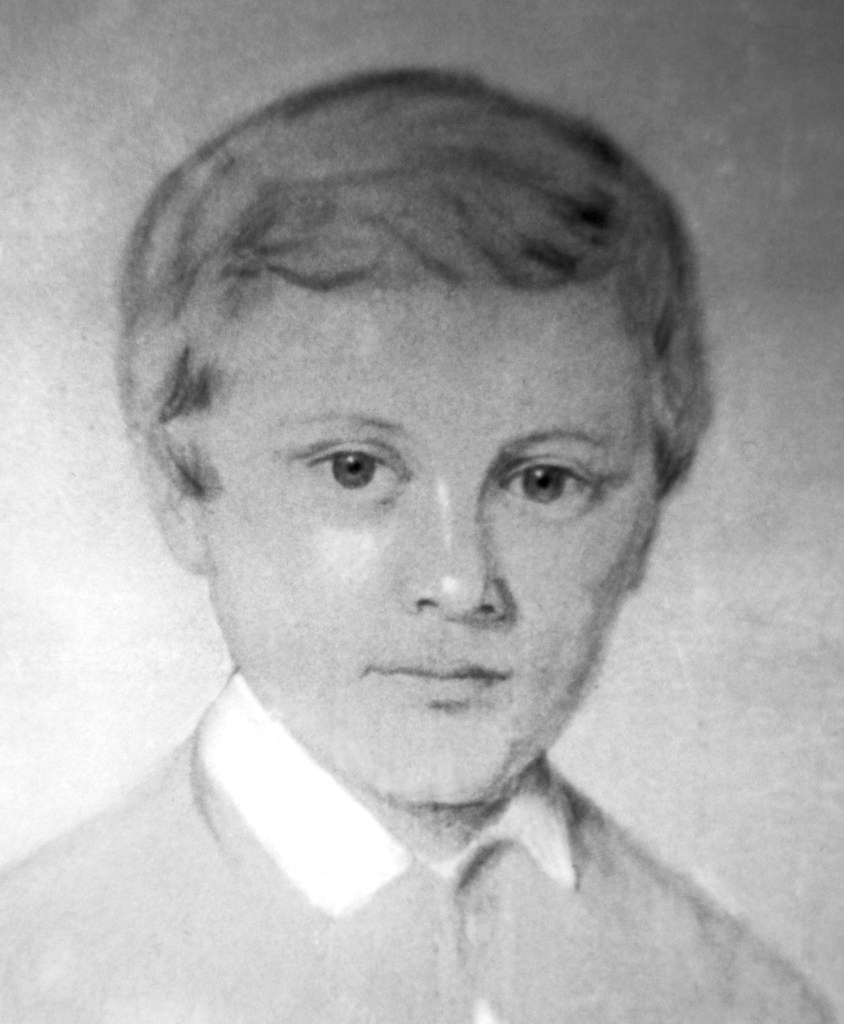

James’ first encounter with his new school-mates at Edinburgh Academy was not a happy one. Having joined late in the term, he was not one of the crowd, rather an intruder to be examined and found wanting. If his father and aunts had had the foresight to dress him like any other schoolboy, he might have got away with it, but his plain rustic garb, such as we see in Plate 2.6, was inappropriate in the new setting.

The tunic, and the square-toed shoes fastened with buckles rather than laces, the frilly collar, are all as mentioned by Campbell in C&G.

By courtesy of the Cavendish Laboratory

This may well be the picture he referred to as having been done by ‘Mrs Tis’, possibly his Aunt Isabella, who sometimes sketched and painted with Jemima. Whoever the artist was, they were close enough to the family to comment disparagingly on John Clerk Maxwell’s grammar.

By courtesy of the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation

His oddness of manner and Gallowegian brogue only served to confirm first impressions: here was a misfit. Children make few allowances in their judgements, and boys will be boys; the nickname ‘Daftie’[6] was handed out to the new lad and the earliest opportunity was taken to show him that he did not fit in. James returned home that afternoon with his clothes bearing full testimony to the treatment he had received in the schoolyard. Nevertheless, according to Campbell he ‘was not in the least inwardly perturbed by all this, nor bore any one the slightest malice’ (C&G, p. 50). One can only wonder on whose side Campbell had been during James’ rough initiation.

It took some time for James to adjust to his new school setting. Even if discipline was more humane and not always directed at himself, his experience under his tutor must have made it difficult for him to accept the dull repetition of learning by rote, while outside the classroom he:

… seldom took part in any games … preferred wandering alone … sometimes doing queer gymnastics on the few trees that were left [in the schoolyard] … his heart was at Glenlair, … (C&G, p. 51)

His hesitancy became more pronounced. He was also frequently absent from school because of childhood illnesses, and when he did attend there were always classmates who would take the opportunity to discomfit him, with the inevitable upshot that his performance in class was not what it might have been. In Campbell’s analogy, he was a ‘cygnet amongst goslings’ (C&G, p. 50). A portrait of James drawn about this time is shown in Plate 2.7.

Thanks to the extensive library at ‘Old 31’, as he now called his new home, James managed to engross himself in the works of Swift and Dryden, and later Hobbes and Butler[7], some of which would have proved difficult reading even for an adult. When his father was in town, they would go for Saturday afternoon walks ‘always learning something new, and winning ideas for imagination to feed upon’ (C&G, p. 52). On one such occasion he was taken ‘to see electro-magnetic machines’, for the latest scientific and technical advances had long been of interest to not only his father but also his uncle, John Cay, Sheriff of Linlithgow. John Cay lived just doors away from James at 11 Heriot Row, and he had been the good friend of John Clerk Maxwell since their days together at the old High School.They were the same age, had studied the law together and had qualified as advocates at more or less the same time.[8] Their common interests led to them becoming Fellows of the RSE in 1821; at that time the requirements for election were not so demanding, the main requisites were being a gentleman of good reputation with a genuine interest in science or the arts, for which they were both amply qualified. John Cay was to take part in similar excursions with his nephew, for example, to visit William Nicol,[9] who at a later date sent James the gift of a polarising prism.

See Figure 2.1 for the general location. Nether Corsock, Over and Nether Blackhills, and Little Mochrum were all part of the estate under the Middlebie entail. Glenlair, together with Upper and Nether Glenlair, were brought into the estate later, in 1839, when John Clerk Maxwell purchased them to make a single estate with the mansion house that he built in 1831 as ‘Nether Corsock’ at its centre. Only from 1839 onwards was this house and estate referred to as Glenlair, whereafter the name Nether Corsock became attached to the steading a little to its north.

Synthesized from DGA: GGD56/1, ‘Plan of Nether Corsock’ by John Gillon, 1806; GGD56/26, ‘Undated Pencil Plan of Glenlair’, 19th C. ; GGD56/13, ‘Glenlair Plan for Entailing’, c. 1839, and other maps of the area.

When his father was not in Edinburgh to divert him, James wrote regularly. But he did not simply observe the customary pleasantries; he took it as an opportunity to let his mind take a creative turn for the benefit of his father’s enjoyment. For example, by:

… concocting the wildest absurdities, inventing a kind of cypher to communicate some airy nothing, illuminating his letters … and adding sketches of school life … drawing complicated patterns … (C&G, p. 53)

Campbell saw this as significant,

… marking the early and spontaneous development of ‘the habit of constructing a mental representation of every problem’, which was in some degree an hereditary proclivity. (ibid.)

By and by, James managed to settle into his new situation and slowly began to progress. By his second year he had managed to get into the top twenty per cent of his class of some seventy boys.[10]His hesitancy, however, still seemed to be something of a problem in Latin and Arithmetic,[11]but by age twelve he could show himself to be top of the class in English and Scripture Biography. In addition, he had managed to prove himself in the schoolyard. A classmate later recounted for Campbell’s book:

On one occasion I remember he turned with tremendous vigour, with a kind of demonic force, on his tormentors. I think he was let alone after that and gradually won the respect even of the most thoughtless of his schoolfellows. (C&G, p. 55‒56)

It was shortly afterwards that James and Lewis Campbell became close friends. Campbell had been in the class since it began, under Mr Carmichael as master, with the intake of 1840. Though James had joined the following year, it was not until about 1843 that their friendship started, and it became all the closer when Campbell’s mother remarried and moved into number 27 Heriot Row, practically next door to James:

We always walked home together, and the talk was incessant, chiefly on Maxwell’s side. Some new train of ideas would generally begin just when we reached my mother’s door. He would stand there holding the door handle, half in, half out, while, ‘Much like a press of people at a door, thronged his inventions’, till voices from within complained of the cold draught. (C&G, p. 68)

James had already done some dabbling in geometry on his own, for shortly after his thirteenth birthday, he mentioned in a letter to his father, ‘I have made a tetrahedron, a dodecahedron, and two other hedrons [sic], whose names I don’t know.’ Amazingly, he had not then had any formal lessons in geometry. When work seriously began on the subject in year five (1844‒45), however, it began to awaken his interest significantly:

Our common ground in those days was simple geometry … but whatever outward rivalry there might be, his companions felt no doubt as to his vast superiority from the first. He seemed to be in the heart of the subject when they were only at the boundary. (C&G, p. 69)

James turned fourteen during the last weeks of that school year, by which time he had had nearly four full years at the Academy; in terms of his steady progress and growing friendships, he seemed completely settled there. When in due course he got the results of the customary end of term examinations, he was able to write proudly to his Aunt Jane, who seems to have been out of town:

I have got the 11th prize for Scholarship, the 1st for English, the prize for English verses, and the Mathematical Medal. [12] (C&G, p. 71)

If winning the Mathematical Medal gives more than ample evidence of progress and branching out, his first prize in English showed he had lost none of his abilities in that direction. The work he submitted was a poem, ‘The gude Schyr James Dowglas’ written in the style of an ancient ballad with language drawn from Barbour’s Bruce. He had researched his topic in several books including Scott’s Marmion, which he was evidently so well acquainted with that he had to stop himself from falling completely into its style and language when he was writing his poem. Throughout his life, Maxwell would turn to poetry to express his thoughts, or simply for a piece of fun, and a number of his verses were recorded by his friend (C&G, pp. 577‒651).[13]

Peter Guthrie Tait (see §16.2) belonged to the class below Maxwell and Campbell but was of much the same age. He was already keen on mathematics and took note of Maxwell having won the school medal; in this way he was drawn into Campbell and Maxwell’s friendship. All three had an awakening intellect that became the basis of a lasting kinship, while their drive to succeed created the most harmonious of rivalries. If Tait tended to excel in Mathematics and Campbell in the Classics, then Maxwell tended to fit squarely in between. The autumn term of 1845 would no doubt have seen Maxwell giving Tait a bit of coaching, enjoying expanding on what he himself had learned. From 1844 on, Tait kept a note-book[14] for the purpose of jotting down what they generally referred to as ‘props’, that is to say, propositions consisting of conjectures, definitions, constructions and proofs. The signature ‘J C Maxwell’ is to be found under an entry in the notebook headed ‘Propositions on the Conical Pendulum’ and dated 25 May 1847, but the writing on the page, including the signature, appears to be in Tait’s hand.[15] This is evident when it is compared with another entry ‘On the Imaginary Roots of Negative Quantities by the Right Reverend Bishop Terrot’[16] signed and dated 27 May by ‘P G Tait’. Another entry signed by Tait has, on the opposite side of the page, ‘J G dedit’ (gave it), while yet another has ‘J G fecit’ (did it); we may presume ‘J G’ to be James Gloag his mathematics master. It seems likely, therefore, that while Tait would copy out things he found of interest, he attributed them conscientiously. The entry on the conical pendulum turns out to have been the solution to a ‘prop’ that Tait had given to Maxwell, which Tait then transcribed into his notebook and dutifully attributed to Maxwell.

Later on Tait and Maxwell would produce their own separate manuscripts on some topic of current interest to add to the collection. Two contributions by Maxwell, ‘Ovals’ and ‘Meloid and Apioid’, are reproduced in C&G, pp. 91−104; some sheets of the original in Maxwell’s own hand are now displayed at the museum at 14 India Street. Another, identified as being in Tait’s handwriting, consists of a few pages of propositions on the ellipse.[17] There may have been an element of competition as well as co-operation in this, with one challenging the other to solve a problem. Tait challenged Maxwell to find the cross-section of a torus (a ring) taken in a plane tangent to its inside surface, but Maxwell found the answer. In turn he gave Tait a highly convoluted question about a heavy body rolling on a curve with the ‘horizontal component of the force, by which it is actuated … to vary as the nth power of the perpendicular upon the axis’ (C&G, p. 116). Little wonder that Tait demurred.

His awakening in mathematics and subsequent rapid success no doubt helped James to appreciate all the better the technical aspects of the latest ideas and inventions. His father must also have taken serious note for, when back in Edinburgh during the winter of 1845−46, he redoubled his interest in attending meetings of the RSE and the Royal Society of Arts,[18] this time taking James along with him. Campbell recalled:

And so it happened that early in his fifteenth year the boy dipped his feet in the current of scientific inquiry … he had always something new to tell … in February 1846, he called my attention to the glacier-markings on the rocks, and discoursed volubly on this subject, which was then quite recent, and known to comparatively few.[19] (C&G, p. 73)

Through the Royal Society of Arts he came across the work of David Ramsay Hay, who at the time was listed as being a ‘decorative painter to the Queen’ (EPD, 1846) and had published not only a volume on the theory of architectural designs but also a reference book of colours:

Such ideas had a natural fascination for Clerk Maxwell, and he often discoursed on ‘egg-and-dart’, ‘Greek pattern’, ‘ogive’ … One of the problems in this department of applied science was how to draw a perfect oval; and … [at age fourteen he] became eager to find a true practical solution of this. (C&G, p.74)

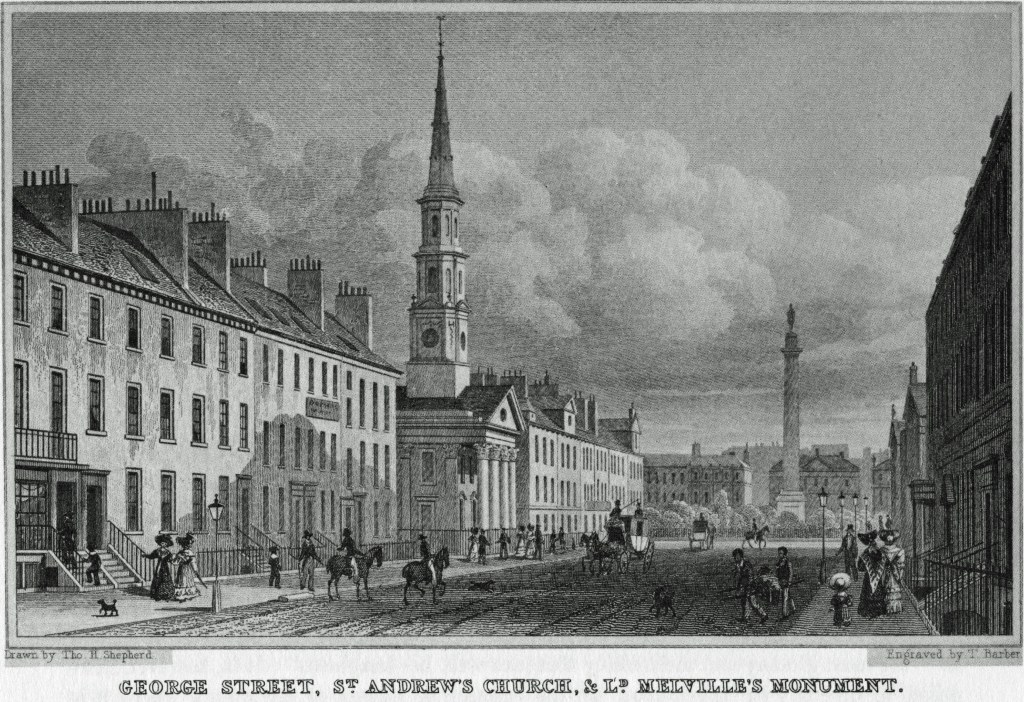

In mentioning a perfect oval here, Campbell means one that is truly egg-shaped rather than merely elliptical. James must have seen various forms of decorative ovals, as well as the gamut of decorative stucco embellishments that went with them, on many a ceiling in the fine houses of the New Town. His own school had a prominent oval cupola perched atop the building, and even St Andrew’s Church, seen in Plate 2.8, where he sat in contemplation on many a Sunday morning, was designed in a grand oval. Edinburgh had taken this classical theme to its heart.

Before they flitted to 11 Heriot Row, Robert Hodshon Cay and his family lived at 2 George Street, the far house on the right side of the street, just before St Andrew Square. The gable-end of the house faced onto the street (follow up from the right-hand lobe of the hat of the lady on the extreme right). Many such buildings have since been replaced, and so the character of the street is now quite different. St Andrew’s Church (now St Andrew and St George’s) was where John Clerk Maxwell would take his son James to the morning service when visiting Edinburgh.

Sometime in late 1845, James must have started looking into this seriously. He may have got what he could on the subjects out of books and from the mathematics teacher, Mr Gloag, who seems to have been the sort of amenable master who would have encouraged such an enquiry. By the following February James had experimented with various ideas for generating his ovals geometrically. It is well known that one can draw an ellipse with the aid of a loop of thread placed over two pins stuck into a sheet of drawing paper. An ellipse will be traced out as shown in Figure A1.1 of Appendix 1 by placing the pencil-point within the loop and pulling it outwards as far away from the pins as it will reach. The shape of the ellipse is varied by changing the length of the loop and by moving the pins further apart or closer together. James worked out an ingenious variation of this method which is shown in Figure A1.2, This he wrote up in a manuscript of the sort that he and Tait were beginning to put together as part of their joint effort on props. To whose attention it first came is not clear, but it would hardly be surprising if it were not Mr Gloag. Perhaps he mentioned to John Clerk Maxwell that it was no mere reinvention of something that was already known; or perhaps it was Mr Hay, who although he was by no means a mathematician, probably knew of every practical method for constructing ovals. In the event, John Clerk Maxwell’s confidence in James’ abilities was such that, in February 1846, he took it to James David Forbes,[20] Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University, for an opinion.

Not only did John Clerk Maxwell know Forbes through the meetings of the RSE (he had probably given the talk on glaciers that James had swallowed up whole), Forbes was a relative[21] and so he could ask his honest opinion without fear of any embarrassment in the event of disappointment. It may well have been this way, for he did not take James’ prop directly to the Professor of Mathematics, Philip Kelland, whom he would also have known through the RSE. Forbes indeed seemed to think there was something in it, and it was he who showed it to Kelland for an opinion, and Kelland duly concurred. Forbes wrote back within little over a week of first seeing James’ actual paper:

3 Park Place, 11th March 1846.

MY DEAR SIR ‒ I am glad to find to-day, from Professor Kelland, that his opinion of your son’s paper agrees with mine; namely, that it is most ingenious, most creditable to him … I think that the simplicity and elegance of the method would entitle it to be brought before the Royal Society. ‒ Believe me, my dear Sir, yours truly,

JAMES D. FORBES (C&G, p. 75)

On 6 April 1846, Professor Forbes duly presented the paper on James’ behalf to a meeting of the RSE under the following heading:

On the Description of Oval Curves, and those having a plurality of Foci. By Mr. CLERK MAXWELL, junior, with Remarks by Professor FORBES. Communicated by Professor FORBES. (C&G, p. 6)

And in due course it was published (Maxwell, 1851)[22] in the same journal that had featured such ground-breaking articles as James Hutton’s ‘Theory of the Earth’ (1788).

John Clerk Maxwell must have been an exceedingly proud man, but there is no indication that it went to James’ head in any material way; on the contrary, it would have had the beneficial effect of consolidating the initial boost to his self-confidence from winning the previous year’s mathematical medal, and it also strengthened his mathematical affinity with Tait. What seems surprising, however, is that Campbell makes no mention whatsoever of any reaction from the Academy; perhaps they considered it a distraction for James, who was not to repeat his previous success when it came to that year’s mathematical prize. All the while, he and Tait continued producing props for their little mathematical club. It is Tait who telss us what James contributed:

‘The Conical Pendulum’, ‘Descartes’ Ovals’, ‘Meloid and Apioid’ and ‘Trifocal Curves’. All are drawn up in strict geometrical form, and divided into consecutive propositions. (C&G, p. 86)

Since these were written during the course of 1846 and early 1847, it may have been that his paper on oval curves started out as an early attempt to produce such a contribution. What a start!

By the time he had reached the age of fifteen, James had blossomed. He had demonstrated a talent for geometry, a subject that requires a different kind of thought from mere words and numbers; points, lines and curves have to be visualised, and relationships have to be explored by logic and construction rather than by mechanical grinding at facts and formulae. Latin, Greek and English verse might amuse him, but geometry enthralled him. He now made rapid progress in mathematics in general and was to take the final year prize. Given his maturity of mind, even at fifteen he must be regarded as being quite the young man, no longer a mere boy. Considering also his success at the RSE, he must have commanded a degree of respect even from his elders. His father’s encouragement, which had been growing since his mathematical medal, must have been even further amplified. Nevertheless, during the late summer of 1846, on the occasion that Campbell made his first visit to Glenlair, we find the pair just being boys, relaxing and enjoying the countryside with few thoughts about geometry and schoolwork.

When they returned to school that autumn for their final year, James’ health was not at its best and he missed many days. But this could not have kept him back from his scholarly interests in general and geometry in particular, for it must have been during this phase that he was pursuing extensions to his work on ovals that developed into contributions to his and Tait’s mathematical props. Campbell relates that he was now also becoming interested in physical phenomena, rather than just abstract mathematical ideas:

He was certainly more than ever interested in science. The two subjects which most engaged his attention were magnetism and the polarisation of light. He was fond of showing ‘Newton’s rings’, the chromatic effect produced by pressing lenses together, and of watching the changing hues on soap bubbles … working with Iceland spar, and twisting his head about to see ‘Haidinger’s Brushes’ [23] in the blue sky with his naked eye. (C&G, p. 84)

This was begun even before he visited William Nicol, who was now approaching eighty, in the spring of 1847. Nicol was a fellow of the RSE and would already have known that James had made something of a mark there in the previous year, and when they met he would have found that James was no one-day wonder. From what we know of James thus far, his knowledge and enthusiasm for the subject must have been obvious to Nicol. His subsequent gift of a polarising prism was perhaps the gesture of an elderly man, one who had made his own mark long time since, doing his little bit to help a rising genius find his way.

According to Campbell, the visit to Nicol:

… added a new and important stimulus to his interest … the phenomena of complementary colours came first, then the composition of white light, then the mixture of colours (not of pigments), then polarisation and the dark lines in the spectrum, then colour-blindness, the yellow spot on the retina, etc. (C&G, p. 84n)

As if that were not enough, shortly after his visit to Nicol, his father took him to a cutler’s shop to choose magnets[24] suitable for experimenting with, an activity that he was still pursuing during his autumn vacation at Glenlair. On that occasion, however, John Clerk Maxwell was taking steel to the local smiddy[25] to be made into magnets for his son. It appears that James was eager to get his magnets because a few days later he and Robert Campbell (brother of Lewis) haunted the smiddy until they got them.

2.3 Undergraduate at Edinburgh

John Clerk Maxwell had by that summer of 1847 arranged for James to start at Edinburgh University in the following November:

In deciding not to continue his [son’s] classical training, he appears to have been chiefly guided by some disparaging accounts of the condition of the Greek and Latin classes in comparison with those of Logic, Mathematics, and Natural Philosophy. (C&G, p.90)

Perhaps this is what he gave out to people when they asked him what James was going to be doing by way of preparing for some profession, which was at that time held to be essential even for the sons of the landed gentry. Could he imagine James as a lawyer or a minister of religion? He had the intellect and the learning, but not the personality, and speechifying was not a strong point. A banker? What interest had he or James shown in making money for its own sake? A doctor, perhaps? That would bring demands that made it more of a vocation than a profession. Being a university professor would suit James in intellect, interest and status, and the long vacations were useful if you had a country estate to look after. Furthermore, would he not have recalled his own situation forty years earlier when he studied the law and became an advocate, only to find that, like his grandfather George Clerk Maxwell before him, he had neither the heart nor aptitude for it? In the event he had decided that James must follow the trajectory along which he was already hurtling.

At the age of sixteen, James duly entered what is now called Old College on Edinburgh’s South Bridge (Plate 2.9), enrolling in mathematics, natural philosophy and logic under, respectively, Professors Philip Kelland, James Forbes and Sir William Hamilton.[26] He was sufficiently advanced in his mathematics to be allowed to enter not the first class, but the second.

Plate 2.9 : Old College, University of Edinburgh

James Clerk Maxwell attended Professor Forbes’ natural philosophy classes here. The lecture theatre and equipment store were located on the upper level, by the three upper floor windows on the far left of the picture. In Maxwell’s last year at the college, Forbes allowed him the use of the facilities there so that he could do his own experiments. A plaque commemorating Maxwell was erected on the facing side of the quadrangle in November 2015.

By the following summer vacation, James had found his niche and was by now hooked on science, as his letters to Campbell on two consecutive days, 5 and 6 July 1848 clearly demonstrate. We give an extract here to give some idea of the flood of things that were going on, all orchestrated in his mind and the whole put into experimental practice under his own inclination and efforts:

I have regularly set up shop now above the wash-house at the gate, in a garret. I have an old door set on two barrels, and two chairs, of which one is safe, and a skylight above, which will slide up and down. On the door (or table), there is a lot of bowls, jugs, plates, jam pigs, etc., containing water, salt, soda, sulphuric acid, blue vitriol, plumbago ore; also broken glass, iron, and copper wire, copper and zinc plate, bees’ wax, sealing wax, clay, rosin, charcoal, a lens, a Smee’s Galvanic apparatus …

With regard to electro-magnetism, you may tell Bob that I have not begun the machine he speaks of, being occupied with better plans, one of which is rather down cast, however, because the machine when tried went a bit and stuck …

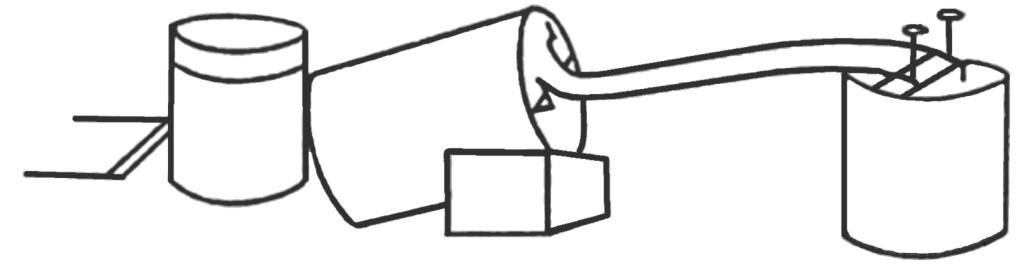

July 6. To-day I have set on to the coppering of the jam pig [Figure 2.4] which I polished yesterday.

I bathe regularly every day when dry, and try aquatic experiments. I first made a survey of the pool, and took soundings and marked rocky places well … also tried experiments on sound under water, which is very distinct, and I can understand how fishes can be stunned by knocking a stone.

We sometimes get a rope, which I take hold of at one end, and … when the water is up, there is sufficient current to keep me up like a kite …

I have made regular figures of 14, 26, 32, 38, 62, and 102 sides of cardboard.

A Latest intelligence – Electric Telegraph [the problematic electromagnetic machine?]. This is going so as to make a compass spin very much. I must go to see my pig, as it is an hour and half since I left it; so, sir, am your afft. friend,

JAMES CLERK MAXWELL. (C&G, p. 118‒120)

Two months later, while still at Glenlair, he revealed that on top of all this, not to mention his diversions with work in the fields, classical reading, time spent in the garden and walking the dogs, he has found time to work on even more ‘props’:

Then I do props, chiefly on rolling curves, on which subject I have got a great problem divided into Orders, Genera, Species, Varieties, etc.

One curve rolls on another, and with a particular point traces out a third curve on the plane of the first, then the problem is :– Order I. Given any two of these curves, to find the third [and so it goes on]. (C&G, p. 121)

His experimental work now consisted of making bits of unannealed glass of various shapes so that he could examine the pattern of internal stresses within the glass by viewing it with polarised light through a ‘crossed’ polarising prism, for example, his Nicol prism.[27]

Figure 2.4 : Maxwell’s homemade experiment for electroplating a ‘pig’

“I have stuck in the wires better than ever, and it is going on at a great rate …” (C&G, p. 119)

That long summer vacation at Glenlair had been an amazing time of discovery and development. He returned to university in November and entered his second year of study. He kept his ‘props’ on rolling curves going on the side before eventually submitting the final draft to Professor Kelland for his opinion, for by this time they knew each other well enough and James was confident enough in his own abilities to do so. Kelland communicated the paper ‘The Theory of Rolling Curves’ (Maxwell, 1849)[28] to the RSE in February 1849, three years after James’ first paper was read there. Having, it seems, sated himself with curves, he then chose a topic that involved both mathematics and physics, the theory of elastic equilibrium in solids, a subject which perhaps occurred to him while peering at bits of unannealed glass and moulded jelly through crossed polarisers.

He started writing this up in March 1850 (C&G, p. 127) and gave it to Professor Forbes, who then put it before the RSE for consideration. The mathematical content was such that they in turn put it out to Professor Kelland for an opinion, and by May James heard back from Forbes that Kelland had read the paper thoroughly and recommended it for publication. But he also warned James that Kelland had complained about ‘the great obscurity of several parts, owing to the abrupt transitions and want of distinction between what is assumed and what is proved’ (C&G, p. 138). He stressed in no uncertain terms that James had to clarify many such parts before the work could go to print. Nevertheless, he had no doubt that James would be able to do so, for the revised manuscript was to be in Professor Kelland’s hands in less than a week! The paper was read shortly thereafter, but it did not appear in print for another three years (Maxwell, 1853).[29] The paper is indeed a tour de force of mathematical physics for someone not quite nineteen years of age.

While one can understand his rapid progress with basic experimental physics through learning, enthusiasm and ingenuity, this reveals something deeper, the penetrating power of his analytical mind, visualising the purely abstract stresses and strains and rendering them into three-dimensional differential equations. Nevertheless, it also shows another side that is hardly surprising in one so gifted; in the written word he occasionally found it difficult to express himself sufficiently clearly for even the most capable of readers to be able to follow him.[30] His Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873a) left Heinrich Hertz so flummoxed that he gave up on it and worked out Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory from the beginning. In his book Electric Waves (1893) Hertz commented:

Many a man has thrown himself with zeal into the study of Maxwell’s work, and … has nevertheless been compelled to abandon hope of forming for himself a consistent conception of Maxwell’s ideas. I have fared no better myself. (p. 20)

Again, the incompleteness of form referred to renders it more difficult to apply Maxwell’s theory to special cases. (p. 196)

On entering his third year at Edinburgh University, Maxwell had completed all the mathematics, natural philosophy and logic that the syllabus offered. He therefore decided to take up moral philosophy under Professor John Wilson[31], chemistry under Professor Gregory, who took the theoretical part, and Professor Kemp, who took the practical work. In addition, he studied German and hung around Professor Forbes’ natural philosophy class where he did not formally attend lectures but was afforded the liberty of using the experimental apparatus for his own investigations. These classes may have proved useful, but other than working on his own prop about elastic solids, he was to some extent marking time. There would have been little point in doing a further year just so that he might receive his degree, and so a decision about his immediate future had become pressing by the summer of 1850.

2.4 Cambridge

There was talk once more about James becoming an advocate. Family and friends were also asking John Clerk Maxwell about his intentions for James and offering their opinions, but it appears that it was well into the autumn before he was at last listening to their advice. In James’ own words:

He had wished me to be an advocate; but I never attended law classes, as by that time it had already become apparent that my tastes lay in another direction. Moreover, he looked up greatly to James Forbes, and desired that I should be like him. (C&G pp. 420−21)

… the existence of exclusively scientific men, and in particular of Professor Forbes, convinced my father and myself that a profession was not necessary to a useful life. (Hilts, 1975, p. 59)

He therefore finally accepted that James should go to Cambridge to undergo the rigours of the degree course there, in other words, to set his sights high and aim for the top. The system was that able students would be chosen and coached for the most exacting of final examinations, the mathematical ‘tripos’. To get that far required a tremendous amount of effort on the part of both student and coach.

Tait, having got enough from just one year at Edinburgh University, was by then already at Peterhouse College embarking on the course. James D. Forbes voiced a strong preference for Trinity (C&G, pp. 132, 146), but John Clerk Maxwell, having received many more recommendations for Peterhouse, at length made the decision to send his only son there, some three hundred miles away from home. Now, this would be nothing remarkable today, and most fathers would not hesitate to send their only son to Cambridge if they could afford it. But at that time sickness and death were ever stalking close by, and so it must have been hard for him, now at the age of sixty, to accept that he would not only see much less of James, but might be seeing him for the last time. The mitigating factors were, however, that travel by train was now well established so that Cambridge could be reached from Glenlair within about twenty-four hours; letters travelled just as quickly; and there was even the telegraph for use in an emergency. Not only was Tait already there, a friend and relative called Charles Mackenzie[32] was a lecturer in Caius College.

In October of 1850, James Clerk Maxwell duly enrolled at Cambridge, in St Peter’s House of Peterhouse College. Robert Campbell, brother of Lewis, had also enrolled, but at Trinity College. Having achieved so much at Edinburgh, James’ first year amongst the freshmen offered him barely enough to hold his attention, and there were the usual distractions of student life. While he did not allow the casual behaviour and occasional merriment of his fellow students to blow him off course, he decided at the end of first year to transfer to the college that Professor Forbes had recommended for him, Trinity.

James, having impressed his tutor William Hopkins, was duly invited to take on the mathematical tripos with Hopkins himself as coach. Hopkins had coached the likes of George Stokes, Arthur Cayley and Phillip Kelland, all of whom became Senior Wranglers,[33] and also the future Lord Kelvin, who by comparison merely managed to make second Wrangler. All four were also Smith’s prizemen, a major accolade for Hopkins. Peter Guthrie Tait was already under Hopkins’ wing and acquitted himself admirably by becoming Senior Wrangler and Smith’s prizeman at the end of 1852. The coaching primarily consisted of ‘mugging up’ on typical examination questions from past papers and the like; obscure strategies and techniques that went beyond the bounds of normal practical methods had to be learned, and the work was both difficult and laborious. James, however, seems to have bent only partially to Hopkins’ coaching methods, for according to Campbell:

… the pupil to a great extent took his own way, and it may safely be said that no high wrangler of recent years ever entered the Senate House more imperfectly trained … But by sheer strength of intellect … he obtained the position of Second Wrangler, and … equal with the Senior Wrangler in the higher ordeal of the Smith’s Prizes. (C&G, pp. 134)

The examination was in January 1854, just a few months after James had suffered a long bout of illness described as a sort of brain-fever (C&G, p. 170). It was put down to the strain of his studies, but it could simply have been a virus. Luckily it came in a break between terms but it left him so weakened that he had to be ‘careful not to read inordinately hard’ in the run up to the final examinations (C&G, p. 171). Nevertheless, if he had been seriously interested in becoming senior wrangler and had focused on doing so by following Hopkins’ coaching more assiduously, he may well have achieved it. But his reluctance to buckle down to it seems to recall the brief spell of rebellion against his tutor in his boyhood. James would have accepted what he did achieve as success enough, as would his father, as would everyone else including his old Professors, Forbes and Kelland. Tait and the Campbell brothers would have been equally pleased for him, and the difference between senior and second wrangler would have been of no account between Tait and himself.

The important thing was what Maxwell was underneath it all, with his personal traits of self-direction and deeply philosophical enquiry; his pursuance of his own ideas and ‘props’; and his insight into mathematical and physical problems. He could not, and would not, have learning drummed into him at the hands of any coach. He had the qualities of genius; and were not his perceived faults, such as Forbes’ complaint about his ‘obscurity’ and ‘abrupt transitions’, evidence of the same inasmuch as they were simply great leaps of insight? Were his spells of distraction not just episodes of absorption in some ‘prop’ or other, as his aunt Jane described it (C&G, p. 105)? Even his faltering speech could be put down to a simple failure to find the words adequate to express the ideas in his mind that were not formed from words, but from abstractions. When put on the spot to say his lesson at the Academy it may have simply been a case of nerves, but the problem stayed with him for a long time thereafter. On the other hand, when he was a student we find people saying he could speak eloquently and profoundly on any subject, and yet we find others who described him as saying little, but to the point. Surely, it very much depended on the circumstances, whether he was comfortable with the situation or whether he felt flustered, as the following example in a letter to Lewis Campbell in February 1857, clearly shows:

Up to the present time I have not even been tempted to mystify anyone [by what I say]. I am glad B‒‒ [34] is not here; he would have ruined me. I once met him. I was as much astonished as he was at the chaotic statements I began to make. But as far as I can learn I have not been misunderstood in anything, and no one has heard a single oracle[35] from my lips (C&G, pp. 265−266)

Another example was when he stood up at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (the ‘BA’) held in Edinburgh in 1850 to challenge a point made by Sir David Brewster (C&G, p. 144n1), who had a fair reputation for cruelly demolishing any theory that did not agree with his own. Professor William Swan[36] later recalled the scene:

His utterance then, most likely, would be somewhat spasmodic in character, as it continued to be in later times, his words coming in sudden gushes with notable pauses between; and I can well remember the half-puzzled, half-anxious, and perhaps somewhat incredulous air, with which the president and officers of the section, along with the more conspicuous members who had chosen ‘the chief seats’ facing the general audience, at first gazed on the raw looking young man who, in broken accents, was addressing them … But, at all events, he manfully stuck to his text; nor did he sit down before he had gained the respectful attention of his hearers, and had succeeded, as it seemed, in saying all he meant to say. (C&G, p. 489)

These recollections of Campbell say much about James’ character, and how he managed to overcome the difficulty he found in speaking under pressure. They may give some clue as to why in later life he was always cautious and measured in what he said, and rarely if ever drew the limelight upon himself.

As soon as his final examinations were over, James was free to revert to his old way of doing things, whereupon he immersed himself in projects that had long interested him and were no doubt constantly brewing in the back of his mind. His mathematical paper ‘On the Transformation of Surfaces by Bending’ (Maxwell, 1856b)[37] may well have followed directly from his earlier analysis of elastic bodies, helped by the lectures of Professor Stokes. It was presented to the Cambridge Philosophical Society just two months later, in March 1854. He also began investigating how to reproduce mixtures of coloured light in a meaningful quantitative way, picking up on the ideas he had taken from Forbes’ demonstrations with a spinning top, which he had doubtless repeated himself. Perhaps out of curiosity, he made himself a rudimentary ophthalmoscope:[38]

To Miss CAY.

Trin. Coll., Whitsun. Eve, 1854.I have made an instrument for seeing into the eye through the pupil … and I can see a large part of the back of the eye quite distinctly with the image of the candle on it … Dogs’ eyes are very beautiful behind, a copper-coloured ground, with glorious bright patches and networks of blue, yellow, and green, with blood-vessels great and small. (C&G, p. 208)

About the same time however, he discovered something which made an interesting and challenging examination problem (Maxwell, 1854)[39]. The idea, suggested to him by the structure of a fish’s eye, was a spherical lens[40] which was more refractive (bent light more) at the centre than at the surface. Maxwell showed that if the variation in refractive power took a certain form, then a point of light on the surface of the lens would produce a perfect image of itself at a point diametrically opposite. That is to say, the lens could focus an object at point-blank range. At the time his idea was more abstract than practical[41] but it gives a clear example of how he was able to think ‘outside the box’. This, however, was only part of what he was thinking about at the time, for he went on to carry out a general mathematical analysis of optical instruments to see what was needed to make a perfect image (Maxwell, 1858)[42].

2.5 Maxwell, the ‘Natural’ Natural Philosopher

Little more needs to be said about the origin and route by which James Clerk Maxwell came to be a physicist, and a great one at that. But we must not forget that he had other sides to his character and intellect. He not only thought about things, he thought about them very deeply, at least until he could get ‘the particular go of it’ in his own mind’s eye. The lectures he received at Edinburgh in Professor Sir William Hamilton’s Logic and Metaphysics classes had stimulated this tendency, for Hamilton was a compelling lecturer on these subjects and James was very much enthralled by them, taking more notes here than in his other classes. At the end of his first year, or perhaps a little later, as an exercise he set for himself, he wrote an essay ‘On the Properties of Matter’. The manner in which this essay came to light shows how much it had impressed Sir William, for it was discovered some years later when he was too ill to continue giving his classes; Professor Baynes, who had been appointed to assist Sir William, found it tucked away in a private drawer in the old man’s desk (C&G,pp. 109).

In order to do it justice, Campbell gives the essay in full (C&G,pp. 109−113). On the age-old problem concerning the nature of a vacuum, Maxwell argued the following:

If we say it is an accident, those who deny a vacuum challenge us to define it, and say that length, breadth and thickness belong exclusively to matter.

This is not true, for they belong also to geometric figures, which are forms of thought and not of matter; therefore the atomists maintain that empty space is an accident, and has not only a possible but a real existence, and that there is more space empty than full. (C&G, p. 110)

This gives some idea of him mentally reaching out as far as he could possibly go to address, if not actually answer, the basic questions that are central to the understanding of physics, that is to say, natural philosophy. Later, on his appointment to the chair of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College, Maxwell chose to make this the theme of his inaugural lecture, given on 3 November 1856.[43]

2.6 A Scottish Professorship

During the winter of 1854, John Clerk Maxwell took ill while in Edinburgh[44] and James returned from Cambridge to be by his side at 18 India Street,[45] which was now where John’s widowed sister Isabella had set up residence; ‘Old 31’ had presumably become too big for her once her children had grown up and, apart from her son George, moved on. Isabella did not keep the best of health herself, but she would have made sure that her brother had plenty of care and attention; even so, James stayed four months and looked after him personally (Riddel, 1930, p. 28‒29). For much of the time he seems to have had little opportunity for anything else, but as soon as his father was on the mend he got back to work. It was during this period that he wrote his first short piece on colour vision, ‘Experiments on Colour Vision as Perceived by the Eye’ dated 4 January 1855.[46] For this he used a simple spinning top and three discs of coloured paper, each slit along a radius so that they could be interleaved to show any proportions of the three colour he wished, before they were spun by means of the top. In fact, he was photographed about this time with just such a top (Plate 2.10). Such was the popular interest in this that J. Bryson, the local optician, took to selling the spinning top and coloured papers for the amusement of his clientele. Maxwell’s conclusion regarding colour vision is accurate, but to the man in the street it sounds like something only a mathematician could come up with:

… the difference between Colour-Blind and ordinary vision is, that colour to the former is a function of two independent variables, but to an ordinary eye, of three. (WDN1, p. 124)

In this paper, he also introduced the now well-known colour triangle diagram showing how to compose any colour from three primaries. This exploited the fact that changing the intensity of a given colour of light does not affect the colour itself, so that one of the three variables involved can be eliminated by choosing it to be the brightness, making it possible to draw a colour composition diagram in two dimensions rather than three.

Plate 2.10 : James Clerk Maxwell at about 24 years of age holding a colour top

Here we can see the mutton chops that were a precursor to James growing a full beard. His hair is already receding a little, but the little tuft sticking up at the front seems to be a throwback to the ringlets seen falling down his brow in Dyce’s portrait of him as a child in the arms of his mother. By courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, University of Cambridge

‘Experiments on Colour, as Perceived by the Eye, with Remarks on Colour-Blindness’ (Maxwell, 1855)[47] was subsequently presented to the RSE just two months later by his old Chemistry Professor, Dr Gregory. In this paper he described several ways of synthesising colour (he had clearly been busy reading up all the information he could on the subject) including his ‘colour box’,[48] his first attempt at which had been in August 1852, doubtless at Glenlair. At this early stage of his academic career Maxwell was making significant headway simply by studying what interested him; he seems to have had a sixth sense for anything that might be significant. It will come as no surprise, therefore, that another gem or two may be found in that article. First, we point out the pearl:

This result of mixing blue and yellow [light to make a ‘pinkish tint’] was, I believe, not previously known. It directly contradicted the received theory of colours, and seemed to be at variance with the fact, that the same blue and yellow paint, when ground together, do make green. (WDN1, p. 146)

Maxwell was therefore one of the first to point out that the mixing of coloured light was not the same as the mixing of pigments (Plate 2.11), because the former is an additive process and the latter subtractive one.[49] But even before he got that far, he had revealed what we must now recognise as a diamond:

This theory of colour may be illustrated by a supposed case taken from the art of photography … Let a plate of red glass be placed before the camera, and an impression taken. The positive of this will be transparent wherever the red light has been abundant in the landscape, and opaque where it has been wanting. Let it now be put in a magic lantern, along with the red glass, and a red picture will be thrown on the screen. Let this operation be repeated with a green and a violet glass, and, by means of three magic lanterns, let the three images be superimposed on the screen. The colour of any point on the screen will then depend on that of the corresponding point of the landscape; and, by properly adjusting the intensities of the lights, &c., a complete copy of the landscape, as far as visible colour is concerned, will be thrown on the screen. (WDN1, p.136)

(a)  | (b) |

| Plate 2.11 : James Clerk Maxwell’s Theory of Three Primary Colours (a) Mixing three primary colours using light. All three colours of light are present where the three circles overlap; they add add to make white. Where only two circles overlap only two colours of light mix, forming yellow, magenta and cyan. (b) Mixing primary colours with pigments. Pigments absorb incident light, so that yellow paint absorbs blue light, red paint absorbs green and blue, while green paint absorbs red and blue. A mix of all three paints absorbs all three primary colours of light, resulting in black rather than white. | |

He had simply, off the top of his head, invented colour photography, and never thought to patent it! The first public demonstration took place at a lecture ‘On the Theory of Three Primary Colours’ (Maxwell, 1861)[50] given at the Royal Institution in London on 17 May 1861. The subject he used was a tartan ribbon tied into a rosette, (Plate 2.12(a)). In truth, Maxwell’s focus at the time was on developing an accurate theory of colour vision, the valuable outcome being his contribution to the understanding of colour blindness.

In October 1855, Maxwell was accepted as a Fellow of Trinity College, that is to say he would teach and give lectures, a position which could have been the basis of a lifelong academic career had he wished to pursue it. As an undergraduate he had followed Faraday’s experimental researches on electricity and magnetism, and had also taken note of W. Thomson’s assertion that there was a close analogy between electrostatics and thermostatics; in conjunction with his mathematical work on elastic deformations, this led him to his first essay in the field of electromagnetics, ‘On Faraday’s Lines of Force’ (Maxwell, 1864 [sic]),[51] a considerable body of work that was read to the Cambridge Philosophical Society in four parts, beginning December 1855. The following February, James Forbes nominated him for fellowship of the RSE despite the fact that he was still only twenty-four years of age.

By this time James was very well settled in Cambridge and had developed a small coterie of close friends; college life being what it is, he felt the loss keenly when any of them had to leave for the sake of following their chosen careers. The only disadvantage was that the academic year was longer than the Scottish one, which had given him the best part of six months in the summer to spend at Glenlair. Nevertheless, he would have been well aware that his father’s health had been failing since his long illness in Edinburgh over the previous winter. As well as being nearly sixty-five years old and somewhat overweight, as we have seen, John Clerk Maxwell was not a well man. There may have been some apprehension between him and James that he was nearing his end.

No doubt wishing to leave James some reminder of himself, he finally had his portrait painted (see Plate 1.1) from which Stoddart engraved the likeness of him that Campbell used in his book . Furthermore, he wished James to be closer to home. As James himself put it:

He much wished me to have a Scottish Professorship, that I might have the long vacation free for living at home. (C&G, p. 421)

(a) |  (b) |

Having put the idea forward in 1855, it was not until 1861, when at King’s in London, that he got round to demonstrating it in public at the Royal Institution in London. It was the first ever photographically produced colour image. The image was not produced as photographic print on paper until 1961 (Evans).

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Plate 2.12(b) : Enlargement of part of the image as displayed on modern TV screen

A TV screen is made up of a large array of tiny ‘pixels’ (picture elements). It can be seen here that each pixel is more or less square in shape and comprises three vertical bars, one red, one green, and one blue, the brightness of which can be individually controlled. At normal magnifications the eye cannot resolve the individual coloured bars and so it sees only the average of the colours they emit. The three separate red, green and blue images formed by the bars therefore correspond exactly to the concept invented by Maxwell some 170 years ago!

It perhaps came naturally to a dutiful son like James, who had become so close to his father since the death of his mother, and likewise his father to him, that when the chair of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College in Aberdeen was advertised, he put his name forward. His father did his bit to solicit suitable references, but sensing that he should once again be by the old man’s side, James came home to Glenlair just days before his father passed away, on 3 April 1856. Sadly, John Clerk Maxwell did not see his fondest wish come true. On his father’s death, James became the new laird and a man of independent means. He already had the Maxwell name and so the only change under the old entail was that he was now ‘Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie’.[52]

James was duly awarded the post just a few weeks after his father’s death. In his inaugural lecture, given to his first class in the presence of the assembled dignitaries of the College, Maxwell discussed at length his own concepts of natural philosophy and physics, but it must be said that he did not draw a distinct line between them.[53] At almost the same time, following his nomination by James Forbes, he was elected as a fellow of the RSE; it was another plaudit to his son that his father did not live to see. Maxwell took up his chair at Marischal College that November[54] already in the knowledge that discussions had been ongoing regarding its merger with its neighbour and competitor, the King’s College. Had it not been for the rancour between those who had been appointed to negotiate the merger, it could have already been under way. Even although his duties were for the most part fairly routine, as indeed they had been at Cambridge, he did take his teaching seriously. Described as having his fair share of ‘misfortunes of the blackboard’ (Lamb, 1931), his insights and asides appealed to his more gifted students. While a good deal of teaching and preparation time was involved, he still had time for his own researches, continuing with colour vision and electromagnetics and now also embarking on the molecular theory of gases, the dynamical top and completing the theory of optical instruments.

As if this were not enough, he had already taken up the challenge of the 1857 Adams Prize Essay, to find an explanation for the rings of Saturn: were they solid, liquid, rubble, or something else entirely? After a good deal of effort on Maxwell’s part, his essay ‘On the Stability of the Motion of Saturn’s Rings’ (Maxwell, 1859)[55] was read on 19 April 1858. It took the prize by showing that the rubble theory was the only one that was stable. Other competitors for the prize seemed to find the problem simply too much for them, and the Astronomer Royal, Sir George Airy, regarded Maxwell’s achievement as one of the most remarkable results of mathematical physics that he had ever seen (WDN1, p. xv ).

If the theory of Saturn’s rings was Maxwell’s first truly great work, his second was only two years in the coming. ‘On the Dynamical Theory of Gases’ (Maxwell, 1860c) was read at the Meeting of the BA[56] at Aberdeen on 21 September 1859 and subsequently published in full as ‘Illustrations of the Dynamical Theory of Gases’ (Maxwell, 1860a)[57]. Maxwell subscribed to atomic theory, which he later made the topic of a poem poking fun at the president’s address to the BA of 1874, of which the following gives the tenor:

How freely he [God] scatters his atoms before the beginning of years;

How he clothes them with force as a garment, those small incompressible spheres!

… Like spherical small British Asses in infinitesimal state …

First, then, let us honour the atom, so lively, so wise, and so small;

The atomists next let us praise, Epicurus, Lucretius, and all. (C&G, pp. 639‒640)

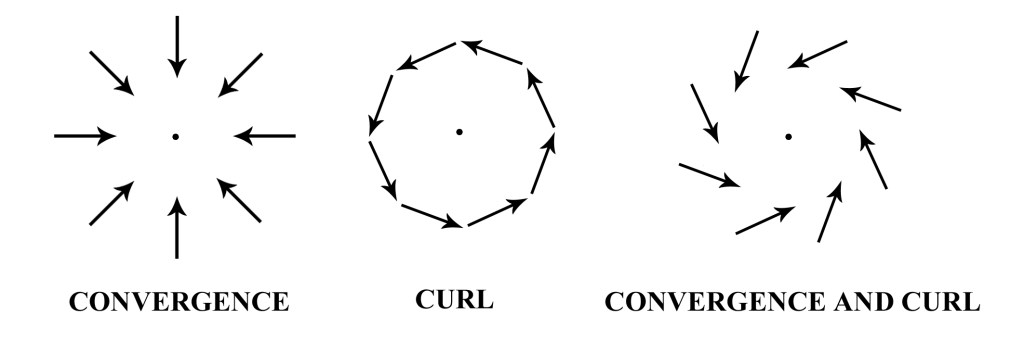

While it was hard to conceive of tiny atoms making up tangible materials like solids, the idea that gases consisted of a cloud of atoms had been mooted by Daniel Bernoulli as early as 1738 in his book Hydrodynamica[58]. We can call them atoms or molecules, it does not matter which, but the underlying theory is usually referred to as the molecular theory of gases. The idea is that in a container filled with a gas, the tiny molecular constituents fly around with considerable velocity. They frequently collide with the walls of the container and the cumulative effect of these collisions acts as a pressure, somewhat like in a hailstorm when a barrage of little icy ‘ball bearings’ loudly drums on a roof. While the average velocity of the molecules depends on the temperature of the gas, Maxwell was the first to show that the molecules do not all have the same velocity, rather they have a statistical distribution of velocities, which he duly calculated (WDN1, pp. 380−381). This distribution now bears his name, along with that of Ludwig Boltzmann, who followed up on his ground-breaking work.

There were other important revelations in Maxwell’s 1860 paper that helped not only to develop molecular theory but to give it sufficient prominence to get others interested; in addition to Boltzmann, Lord Rayleigh was also impressed by it (Jones, 1973, p. 65−66) and Sir James Jeans referred to much of Maxwell’s original work in his celebrated ‘The Dynamical Theory of Gases’ (1904), which even the title recalls. Maxwell’s other publications during his time at Aberdeen are perhaps overshadowed by these masterpieces on the molecular theory of gases which, as we shall see, could hardly have been appreciated by either his fellow academics or the City Council.

It was in association with the Aberdeen instrument makers Smith and Ramage (Maxwell, 1860b) that Maxwell produced:

- the final version of his colour mixing box;

- his fully adjustable version of the dynamical top, a copy of which was provided to his old teacher and mentor back at Edinburgh, James Forbes;

- a mechanical model of the behaviour of the rings of Saturn.

- The model of Saturn’s Rings had been conceived in December of 1857 (C&G p. 295) and was demonstrated to some acclaim at a lecture given at the RSE (Maxwell, 1857‒62) in which he summarised the conclusions of his prize essay.

. ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ .

The principal at Marischal was the Reverend Daniel Dewar, with whom Maxwell forged a friendship that brought him in contact with Dewar’s daughter, Katherine who, although seven years his senior, was not yet spoken for. Maxwell was invited to stay with the Dewars when they were on their annual vacation near Dunoon in the September of 1857, which must have afforded ample opportunity for Katherine and him to get acquainted. Perhaps Daniel Dewar and his wife had hoped as much in extending the invitation. The following February, James and Katherine were engaged and the wedding took place at Aberdeen in June 1858, whereafter the couple lived with the Dewars at 18 Victoria Street (Jones, 1973, p. 64).

Maxwell seems to have been very happy in his choice of wife, but it was not well received by his family back in Edinburgh. This may well be due to the fact that he did not consult the senior family members beforehand or, if he did, he was going against their advice. John Clerk Maxwell had perhaps thought that the task of seeking a wife for his son could wait until after he had his professorship, but of course it was now too late. Maxwell’s aunts Isabella and Jane would have naturally spent some time thinking about such things, and would even have pressed John to do the same, but in the event they were taken by surprise when James simply announced his engagement out of the blue:

18th February 1858

DEAR AUNT [Jane,] This comes to tell you that I am going to have a wife … So there is the state of the case. I settled the matter with her [mother], and the rest of them are all conformable … I hope someday to make you better acquainted … For the present you must just take what I say on trust. So good-bye. Your affectionate nephew. (C&G, p. 303)

By what he says elsewhere in the letter, Aunt Isabella, his uncle John Cay and Sir George Clerk, the most senior figure on his father’s side of the family, effectively received carbon copies of the same. They may therefore have been just as surprised, and perhaps Aunt Isabella and Sir George would have been offended that he had not seen fit to consult them, for James should have been thinking about the future of Middlebie, and potentially of Penicuik. James’ choice lacked any sort of alliance with a comparable family. Genteel as the Dewars may have been, Daniel Dewar was not landed gentry;[59] he had no estate of his own and had to go to his son-in-law’s when it came to summer vacation! For Sir George, the news would have been unwelcome indeed, and he may even have gone so far as to put a shot over the young man’s bows.

The issue was that, theoretically at least, James, or any children that he might eventually have, could at some time end up being successors to, or having an interest in, the Penicuik estate; Sir George did by then have grown-up sons and grandsons of his own, but it may be that he was just as upset because James hadn’t even considered the wider possibilities. On top of that, there were other legal matters that could be affected, for example, debts owed by John Clerk Maxwell’s estate to Sir George. At any rate, on 3 March Sir George served James with a ‘summons declarator’,[60] a fairly prompt riposte considering James had written to announce his engagement barely a fortnight before. The pretext was that improvements had been made over the years to the Penicuik estate, for which John Clerk Maxwell had had some sort of legal or financial liability. It was all spelled out in detail in the summons, amounting to a total of £6,777 11s 1½d, [61] an enormous sum at the time, probably thirty times a typical professorial salary.

This information has only recently come to light and what happened in consequence is not yet known. Both the timing of it, and the fact that it ever took place, seems to reveal the gut reaction of a man of the old school, who simply saw James’ behaviour as unacceptable. When James was a boy he had often visited Penicuik House, especially in the Christmas holidays, but whereas there are frequent mentions of various uncles and cousins within his mother’s and aunt Isabella’s branches of his family, the only mention of Sir George in Campbell and Garnett’s biography occurs when James wrote to inform him of his father’s death (C&G, p. 254).