Briliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

12.3 From the Irvings of Newton to the Irvings of the New Town

12.4 A Case of Multiple Connections

12 The Enlightenment of Edinburgh

It has already been mentioned that following the Union of the Scottish and English Parliaments in 1707 there began a remarkable period in which all branches of the sciences and the arts flourished, and it was all the more remarkable because Scotland had been until then one of the smallest and most deprived countries in Europe (Daiches et al., 1986). As the economic situation improved during the eighteenth century, however, men of exceptional ability found outlets for their talents and thus emerged as towering figures who have in some way or another made a lasting impression on the world. John Amyatt, a Londoner who was appointed the King’s Chemist from 1776 to 1782, had stayed long enough in Edinburgh to become a fellow of its former Philosophical Society, and although by 1783 he was no longer a resident, he was nevertheless admitted as a founding member of the RSE, along with many of the men that he was referring to in the following remark reported by his friend, William Smellie (1740−1795), editor of the first Encyclopaedia Britannica:

Mr Amyat … one day surprised me with a curious remark. ‘There is not a city in Europe, said he, that enjoys such a singular and such a noble privilege.’ I asked, ‘What is that privilege?’ He replied, ‘Here I stand at what is called the Cross of Edinburgh, and can, in a few minutes, take fifty men of genius and learning by the hand.’ (Smellie, 1800)

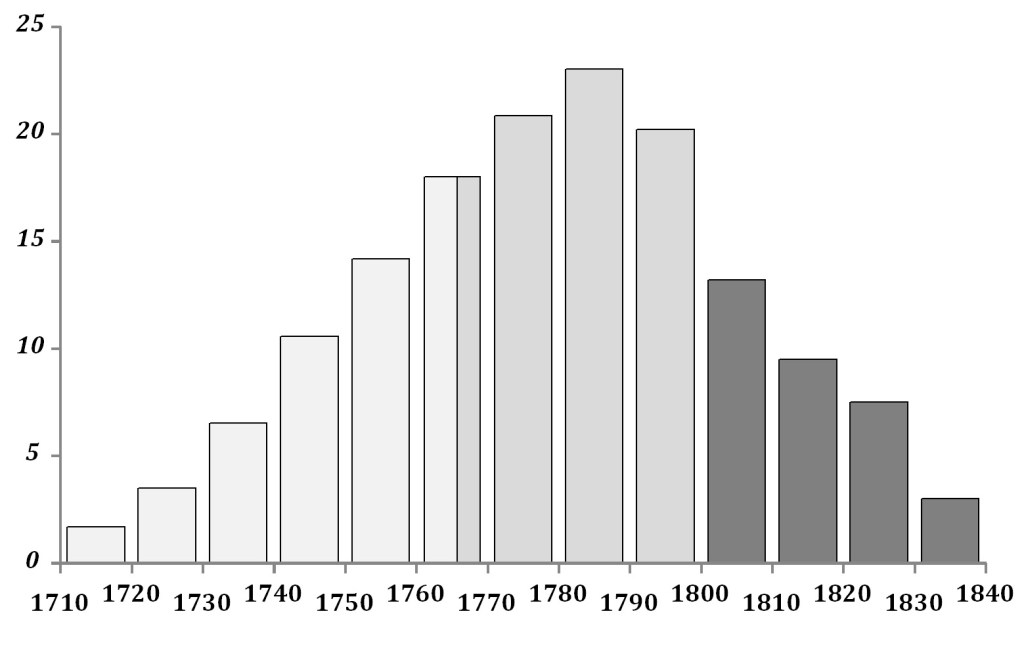

Under the topic ‘Scottish Enlightenment’ on Wikipedia (2015), of the thirty-seven people suggested as being the most eminent of the enlightenment, twenty-three flourished in the decade 1780−89, not far removed in time from when the remark was made. Given that these represent only the top stratum of such noteworthy people, largely concentrated in Edinburgh, Mr Amyatt could easily have demonstrated the underlying element of truth in his claim. Their number increased progressively from two in the decade 1710−19, to its peak of twenty-three in 1780−89 and thereafter decreased almost symmetrically to about two again in 1830−39. It is not that we had run out of such men of genius, it was simply that they stood out so much less amongst the growing number of well-educated, highly competent people across the world, while at the same time the bar for genius was consequently rising. If the Scottish heroes of the enlightenment, notable examples of whom are given in Appendix 5, had been amongst the first to shine their light in the dark, by the time the nineteenth century was well under way there was light everywhere. By this one crude measure alone, as shown in Figure 12.1, we may chart a timespan of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Out of a total of 37 leading figures, about two thirds were active during the decade 1780‒90 when the population of Edinburgh itself was still less than 150,000. The first and second new town eras are indicated by the mid-grey and the darker bars respectively.

Edinburgh’s new towns were not only a product of this age of enlightenment, they form a magnificent and lasting testament to it. The grandeur of the buildings, laid out to the overall design of James Craig (1739−1795) (Coghill, 2010, p. 143; Youngson, 1966, pp. 70−110, 288−289) gives some idea of the talent and ambition that abounded in this golden era. But before discussing the new towns, which were very much the scene for James Clerk Maxwell’s immediate family and their circle of friends and relatives, we must begin with the Old Town.

12.1 The Old Town

James Clerk Maxwell grew up when Edinburgh’s New Town was burgeoning. The Old Town, as shown in Figure 1.1, dated from mediaeval times and as we have seen, had once been the place to live for great and humble alike. Hemmed in by the great wall that had been thrown up as protection after the momentous defeat of the Scots at the battle of Flodden in 1513, the citizens were constrained to expand their town in an ever upward direction. Making use of the steep gradients that run down on each side of the High Street ridge that flows gently down to the east of the castle, their stone tenements, or lands, were built to great heights, especially on the sides facing the valleys of the Cowgate and Nor’ Loch (Topham, 1899, p. 2):

The style of building here is much like the French: the houses, however, in general are higher, as some rise to twelve, and one in particular to thirteen storeys in height. But to the front of the street nine or ten storeys is the common run; it is the back part of the edifice which, by being built on the slope of an hill, sinks to that amazing depth, so as to form the above number.

Closely packed, and getting wider and more higgledy-piggledy as they rose, it is said that neighbours in the upper reaches of two adjacent lands could easily touch hands, or even lips, from their viewless windows (Chambers, 1980, p. 4), which notion is expressed very well in Figure 12.2.

Figure 12.2 : ‘Dickson’s Close

Viewed from above, the High Street was like the backbone of a herring, with the lateral bones corresponding to a multitude of steep and narrow alleys, wynds and closes, running down from it on either side. Many of these remain, but there are few examples left of what we see in the figure, where the barely separated tenement buildings, or lands, were allowed to reach ever closer as they went up. While this gained the occupants more floor space, it did little to afford them fresh air and light. The gentlemen sharing the book must have been good friends to have been able to put up with living so close together.

From Dunlop et al., 1886

Robert Louis Stevenson gives a romantic view of these lands of the Old Town at the time of his boyhood in Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes (1879, pp. 5−9). The tradesmen and shopkeepers occupied the floors nearest the ground, while the gentry occupied the airier floors just above. Thereafter, the spectrum of affluence rapidly decreased with height, with the uppermost levels being divided into many small apartments each packed with a large family of the poorest people. Notwithstanding, all was accessed by a narrow common stair, which in many of the oldest buildings would have been a wooden structure that rambled up the outside of the building. While fresh water was fetched from a number of common wells at street level, and had to be carried up to the giddy levels above, the problem of returning waste water of any kind, indeed waste of any kind, back to street level was much more easily dealt with. On the sounding of the town guard’s tattoo at ten o’clock each night, and theoretically not before, the obedient citizens would duly tip their buckets out of the nearest window to the cry of ‘Gardyloo’, which was often greeted with a cry of ‘Haud yer hand!!’ from some panic-stricken reveller who had missed his way home.

12.2 The New Towns

From about 1750, in the Scottish Lowlands, security was less of a concern and prosperity was on the increase, at least for those who were well placed to grasp it. The town’s gentry began to yearn for more refined surroundings, and many managed to escape the city by building villas to the south of the University, or College as it was then known (Chambers, 1980, p. 4):

Edinburgh by-and-by felt much like a lady who, after long being content with a small and inconvenient house, is taught, by the money in her husband’s pockets, that such a place is no longer to be put up with.

By the 1760s, however, a scheme was being discussed to build houses on a grander scale to the north of the town. Land was acquired and in 1767 work began on James Craig’s formal plan (Youngson, 1966). Within ten years the ‘New Town’ was taking shape and such noteworthy folk as the philosopher David Hume decanted to the other side of the Nor’ Loch[1] (Chambers, 1980, p. 58). Each new house that was built realised just one small part of a grand master-plan, but they were no less grand in their own right. Typically they were built of quarried stone, comprised three floors and one or two basements, had large windows and were often ornamented with splendid columns and balustrades. A few, such as the house of Sir Lawrence Dundas, on the East side of St Andrew square, were magnificent classically inspired edifices in the grand Georgian style. On the interior, many were decorated by Robert Adam, or in his style; they represented an opulence that only a very few could aspire to by the standards of today. At that time, however, many of those who made it to the New Town were what we would consider as being moderately rather than very wealthy. Well-to-do merchants and master tradesmen built houses in the same streets as lawyers, physicians and Lords and Ladies. In Edinburgh at least, the snobbery associated with class distinction was something for the future, when people started equating the grandeur of each house to the social status of its inhabitants.

While Craig’s New Town plan to the north of the Old Town was the officially adopted version promoted by Edinburgh’s Lord Provost George Drummond, George Square to the south of the Old Town (see Figure 1.1) was part of a slightly earlier informal development which was begun in 1766. Much land had been freed up in the vicinity by the draining of another loch, actually more of a marshland, the old Burgh Loch which is now a public park referred to as ‘the Meadows’, and it had the distinct advantage of being quite level. Built by James Brown and named after his brother rather than the King, George Square was not part of any grand design similar to Craig’s, and because Drummond’s efforts were directed towards bringing Craig’s plan to fruition, it did not spread to any great extent.

George Square is the largest of its kind anywhere in Edinburgh, but while its original houses are smaller and of a rougher external appearance to those in the Second New Town, they are actually similar to the majority of those that were erected about the same time in the First New Town[2]. They would have been, almost literally, a breath of fresh air compared with the hemmed-in Old Town dwellings. From at least 1800 to 1808, 47 George Square was the home of Mrs Janet Clerk (Irving) and her three children, George, Isabella and John (see §9.3). It was close by the University and also fairly convenient for the old High School, which the boys would have attended, as did the future Sir Walter Scott, who was somewhat older but who had also lived in George Square (see Figure 1.1 locations 5 and 6).

Within just thirty years of the commencement of the First New Town, a second New Town was called for, and about 1803 building began on Heriot Row. When Henry Mackenzie, author of Man of Feeling, was living in one of the first to be built there, he recalled the land as it had been before the new houses were started; he had shot snipe there in the fields of Wood’s farm lying between Canonmills and Bearsford Park[3] (Grant, c. 1887, vol. 2). Another thirty years saw the area north of Queen Street (Figure 1.1) largely built up. Considering that many other developments to the east, south and west are not shown in the map, the overall rate of expansion of Edinburgh was truly enormous. Today, the New Town refers to the entire development of both the First and Second New Towns, characterised by buildings of quality in the Georgian style harmonising with wide streets and numerous gardens conforming to a geometrical layout. [4]

Many of James Clerk Maxwell’s forebears and their kin lived in Edinburgh, and most of them who were alive in the New Town era made the move from the lofty old tenements in and around the Old Town to the brand new terraced villas to the north and at George Square to the south. Using information collated from various sources, including the Edinburgh directories from 1773 on, Table 12.1 shows where they lived both before and after they moved. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 may be used to locate a number of these New Town addresses.

Table 12.1 Addresses of the Clerks in Edinburgh’s Old and New Towns

Baron Sir John Clerk, 2nd Bt. Blackfriars Wynd

Sir James Clerk, 3rd Bt. Blackfriars Wynd; Sempill’s Close

Lady Elizabeth Clerk (nee Cleghorn) Dickson’s Close

George Clerk Maxwell, 4th Bt. James’ Court

Dorothea Clerk Maxwell James’ Court; 52 Princes Street

Sir John Clerk, 5th Bt. James’ Court (c/o Mrs Shaw); 37 Princes Street

Lady Mary Clerk (nee Dacre) Crichton Street; 37 Princes Street;

57(100) Princes Street

John Clerk of Eldin Shakespeare Square; Hanover Street;

70 Princes Street;16 Picardy Place

Capt. James Clerk, HEICS James’ Court; 52 Princes Street

Mrs Janet Clerk (nee Irving) Buccleuch Street; 52 Princes Street;

37 Princes Street; 47 George Square;

31 Heriot Row; 14 India Street

Sir George Clerk, 6th Bt. 47 George Square; 31 Heriot Row; London

Isabella Wedderburn (nee Clerk) 47 George Square; 31 Heriot Row;

126 George Street; 31 Heriot Row;

18 India Street; 25 Ainslie Place

Baron James Clerk of Rattray George Square; 53(92) Princes Street

John Clerk, Lord Eldin 70 Princes Street; 16 Picardy Place

William Clerk, of Eldin 70 Princes Street; 1 Rose Court; 4 Rose Court

John Clerk Maxwell 47 George Square; 31 Heriot Row;

14 India Street; Glenlair

Frances Clerk Maxwell (Cay) 11 Heriot Row; 14 India Street; Glenlair

Old Town addresses are in italics while the underlined house numbers are pre-1811 designations. The numbers in brackets show the later designations, where available.

12.3 From the Irvings of Newton to the Irvings of the New Town

Of the first George Irving of Newton we now know at least a little: his parentage, how he acquired Newton, his marriage and children, his qualification as a Writer to the Signet, and his career with Edinburgh City Council (see §11.2). George died in June 1742, whereupon he was succeeded by his eldest son Robert, who then died in 1748 leaving it to his brother George, the second George Irving of Newton, about whom we have been able to find very little information. We may assume, however, that as the second son he was at the earliest born in 1713; he died in early November 1782,[5] having married twice. Referring to Family Tree 6, His first wife was Isabella Colquhoun,[6] who was the daughter of James Colquhoun,[7] Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1738 to 1739, and his wife Janet Inglis.[8] George and Isabella were married on or about 22 March 1757 and a year later a child, Janet Irving, James Clerk Maxwell’s paternal grandmother (see §9.2), was born. Within the space of just a few years Isabella had died, whereupon George remarried Mary, or Molly, Chancellor, daughter of Alexander Chancellor of Shieldhill near Biggar, on 22 September 1763. Curiously, his younger brother Thomas, the surgeon, married Molly’s sister, Jean or Jane Chancellor, of which more in the following chapter. Of Janet, the only information we have of her follows her marriage with James Clerk HEICS in 1786, the story of which was taken up in §9.3. We may suppose she was born between, say, 1758 and 1761, and would therefore have been between twenty-five to twenty eight years of age at the time of her marriage.

The children of George’s marriage to Molly Chancellor were:

- Alexander (1766−1832), who was an advocate (1788), mining manager at the Scots Mining Company at Leadhills, joint Professor of Civil Law at Edinburgh University (1800) and later a Judge, Lord Newton (1826).[9] He married his cousin Bethinia in 1814. Since her parents were Dr Thomas Irving and Jean Chancellor, respectively the brother of his father and the sister of his mother, there was a high degree of consanguinity in this marriage.

- John (1770−1850)[10] was a Writer to the Signet and an early friend of Sir Walter Scott. Amongst other things he was a director of the Bank of Scotland, and became wealthy. In 1804 he married Agnes Clerk Hay whose grandmother was Agnes Clerk, daughter of George and Dorothea Clerk Maxwell, and as we will see, some of their children’s achievements were noteworthy.

- Thomas (1774−1852) left Edinburgh to go into the Civil Service and eventually settled in London. His first wife Margaret Colhoun was connected through her mother Rebecca Napier to the Napiers of Merchiston. It is not known whether her father, John Colhoun, had any connection with Isabella Colquhoun (frequently also spelled Colhoun), his father’s first wife.[11]

- There were also three sisters, of whom we know but little. Elizabeth we know of only because of her death in April 1808 (Scots Magazine, 1808, p. 399), which Sir Walter Scott said affected John Irving very much.[12] The two other sisters that we know of are Mary and Jeannie (Fairley, 1988, p. 111) who were likely to have been the two elderly ladies depicted in Jemima’s watercolour (Wedderburn, c. 1841) of James Clerk Maxwell’s arrival at Newton House in November 1841 while on his way to Edinburgh (see §2.2).

Janet was therefore the half-sister of Alexander, John, and the other children.

One might suppose that George Irving never lived much on his estate at Newton (shown in Plate 11.1) for although there was, a house there, the countryside for miles around was, and mainly still is, desolate moorland surrounded by hills and transected by water. Newton itself was not the entirety of his estate, for according to Irving (1907), it also comprised lands at ‘Partraith, Over Fingland, Shortcleugh and others’.[13] Now, it was on South Shortcleugh that George Clerk Maxwell and his mining partners took out a tack with the Earl of Hopetoun in 1758 (see §8.13). In addition, since George Irving’s son Alexander is known to have been involved in mining in that area, it would come as no surprise at all to find that George Irving himself was interested in the mines either on his own property or on neighbouring holdings where he may have been involved in a partnership. We know so little about the second George Irving that we simply cannot say either way, but if he did have mining interests he would have spent rather more time at Newton than otherwise.

As to an Edinburgh residence, we find him in the available directories for only one year, 1775, when ‘Irvine, George Esq.’ was at Milne’s Court, in the Old Town, at the top of the Lawnmarket. In the previous year, it was his brother Thomas, the surgeon, who was listed at that same address.[14] After George’s death, his widow was in Bristo Street in 1786, listed as ‘Irvine Mrs. of Newtown’, while her sister Jean, listed as ‘Irvine Mrs. Dr.’ was elsewhere, at Sommervile’s Close in the Canongate. Bristo Street, as it was then, lay just beyond the city wall, close to George Square. The houses there had appeared piecemeal even before the New Town expansion. In 1775, therefore, the Irvings were still pretty much in the Old Town, but by 1786 they were in the vicinity of George Square, the alternative New Town development touched on in §12.2. After the second George Irving died in the winter of 1782, Alexander, his heir, would have come into Newton in his own right by 1787, the year before he qualified as an advocate. Listed under his mother’s name and in due course his own, for nine years the Irvings are to be found at Bristo Street, after which they moved ‘round the corner’ to 5 Buccleuch Place, shown as location 7 in Figure 1.2, a mix of recently built town houses and tenements adjacent to George Square. In this tenement, comprising four storeys entered by a common stair, they remained until 1805 with Alexander as the head of the family. In 1806, however, Alexander Irving of Newton, Advocate, now joint Professor of Civil Law at Edinburgh University, was to be found living at Heriot Row, listed as number ‘8 on the west side’. In 1811, when the numbering changed to the present -day system, this became 27 Heriot Row, the same address at which James Clerk Maxwell called for his schoolfriend, Lewis Campbell! [15].

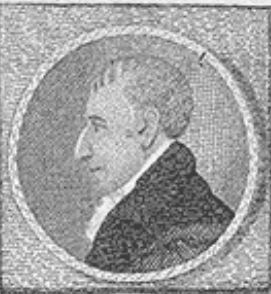

Plate 12.1 : Alexander Irving of Newton

From John Kay’s ‘Twelve Advocates that Plead Without Wigs’ (Kay, 1838).

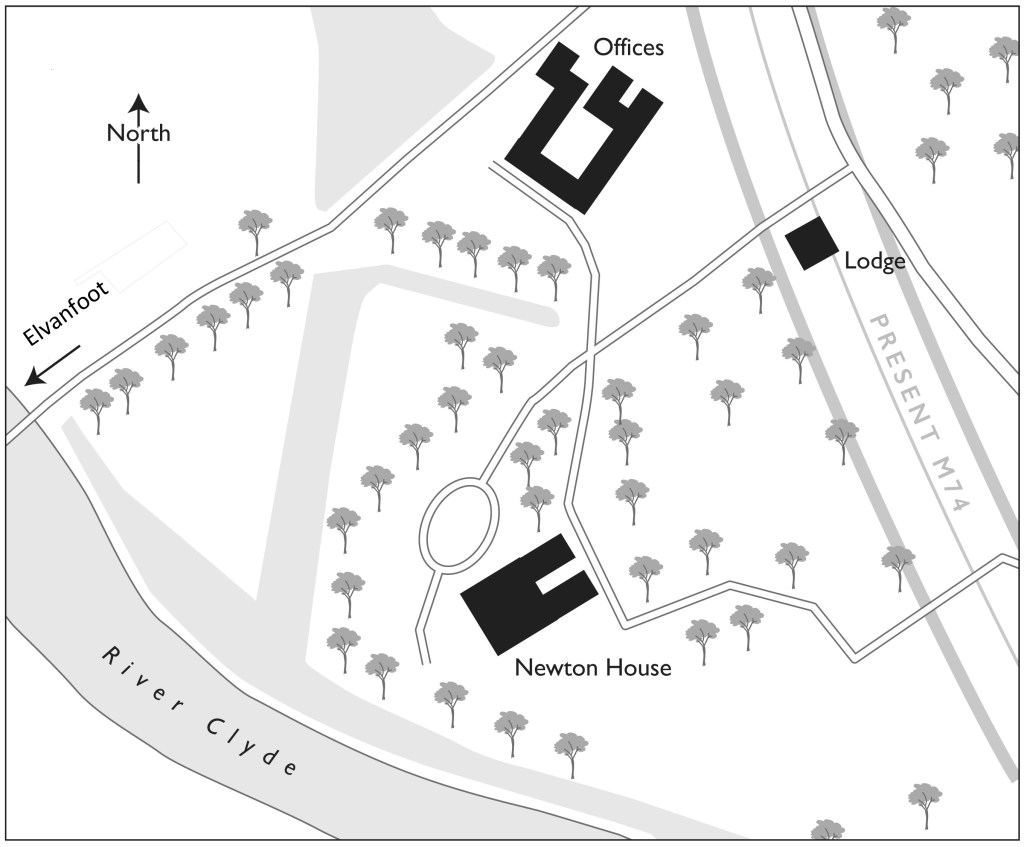

As an advocate and as a judge in the Court of Session , the character of Alexander Irving, later Lord Newton, seems to have been the antithesis of his contemporary, Lord Eldin, to whom he was related by his half-sister Janet’s marriage to James Clerk HEICS. Although he was completely lacking in Eldin’s force of character, he was particularly successful as a judge in his own particular sphere of activity.[16] In 1814 he married, at the age of forty-seven, his first cousin Bethinia Irving, who was the daughter of his father’s brother, Dr Thomas Irving (see Family Tree 6). In 1815 they had their only child, a son they named George Vere Irving[17] (the co-author of Irving & Murray, 1864). Alexander used his wealth to build a large mansion on his estate at Newton (Plate 12.2), the site of which can be seen in Figure 11.1 and 12.2. It was here, as depicted in one of Jemima’s watercolours (Wedderburn, c. 1841), that the Clerk Maxwell family would stop over on their journeys between Glenlair and Edinburgh.

from Irving & Murray (vol. 3,1864)

Alexander died on 4 March 1832, after bravely enduring what must have been an excruciating operation to remove stones from his urinary tract, a trial he bore with great fortitude. His great-nephew James Clerk Maxwell was then only nine months old. Alexander’s widow lived on at 27 Heriot Row until 1842, the year her son married, and thereafter she decamped to 2 George Square.

It appears that James Clerk Maxwell would have known his great aunt Bethinia when he first came to live at Heriot Row. She died about 1854, and is buried alongside her husband Alexander and his father and mother, George Irving and Mary Chancellor, in St John’s and St Cuthbert’s churchyard.

A bridge still provides access from the village of Elvanfoot, but alas the original mansion built by Alexander Irvingis no longer there

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

Alexander and Janet Irving had two younger brothers: John, born in November 1770, and Thomas, as shown in Family Tree 6. As discussed in §9.1, John Irving, along with William Clerk, second son of John Clerk of Eldin, was one of Sir Walter Scott’s closest friends. They were of much the same age and were neighbours, Scott in George Square and Irving in nearby Bristo Street[18]; both would have gone to the High School and we know that John Irving was there with Scott and William Clerk when they paid an impromptu visit to Sir John and Lady Mary Clerk as Penicuik house. At the time of that visit, Janet Irving had already married Sir John’s younger brother, James Clerk HEICS, so that John was in fact ‘family’.

Unlike Walter Scott and William Clerk, however, John Irving’s legal career was not as an advocate. His older brother Alexander having already taken that route, it was his lot to become a Writer to the Signet, which he accomplished in July 1794. Ten years to the month later, he became further connected with the Clerks of Penicuik through his marriage to Agnes Clerk Hay, a great-granddaughter of George Clerk Maxwell, 4th Baronet; and they had a large family.

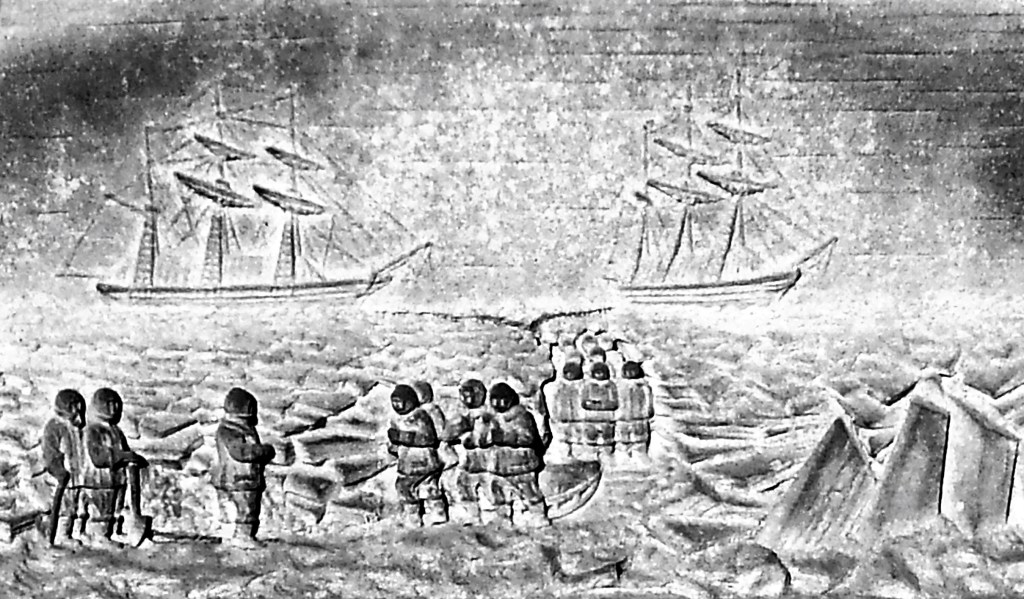

Their fourth son, John, was born in February 1815. We mention him first because he was to achieve fame something akin to that of the heroes that accompanied Captain Scott on his Antarctic expedition, but alas it did not come in his lifetime. After attending Edinburgh Academy as one of the first intake of pupils at the newly opened school (Henderson & Grierson, 1914) he went to Portsmouth Naval College where he excelled and took the second prize silver medal in mathematics before passing out as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy (Bell, 1881). After several years’ service during which he failed to get promotion, in 1837 he left for Australia in fulfilment of a plan to become a sheep farmer there. Nevertheless, while on a trip to Sydney in 1841 to sell wool, he happened to spy HMS Favorite lying in the bay and, having encountered some of its officers whom he knew well, he was persuaded to return to the Navy. Having done so, he joined the ill-fated Franklin Expedition that set out to navigate the North-West Passage in 1845.

Despite the two ships Erebus and Terror having been strongly built, strengthened with iron plates and equipped with steam power (Bourne, 1852, Appendix: p. i),[19] they became lodged in the ice in Baffin Bay, and so it was that he perished, along with the rest of the crew, in the vicinity of King William Island sometime between 1848 and 1849. There his remains lay frozen and undisturbed until they were discovered in 1880 by a search party led by Lt Frederick Schwatka of the US Army (Sydney Morning Herald, 1881). His remains were identified by his silver medal, which his comrades had placed beside him in his shallow grave before they too met their fate. After their discovery, his remains were returned to Edinburgh and buried with full honours in the Dean Cemetery to the west of the New Town on 7 January 1881. The funeral procession, led by his brother Alexander and sister Mary, who was by then Mrs Scott Moncrieff (see note 29 to Chapter 5), departed from Mary’s home in Great King Street, another fine Second New Town address just to the north of Heriot Row. His monument in the Dean includes a bass relief plaque depicting the expedition (Plate 12.3)

John and Agnes had several other children, the eldest of whom was George (1805−1841), named after his paternal grandfather. He followed in his father’s footsteps, first by becoming his apprentice and then, in November 1828, a Writer to the Signet. He died at the age of thirty-five in February 1841 without either having married or having had the opportunity to fulfil his potential to the sort of extent that some of his siblings managed to achieve.

The second son was Lewis Hay (1806−1877), named after his maternal grandfather who had been a colonel in the Royal Engineers. He trained for the ministry of the Church of Scotland and by 1830 had become the minister of Abercorn church on the Hopetoun estate near Queensferry (Scott, 1915, vol. 1, p. 191). During the ‘Disruption of 1843’ (Scotland.org, 2014; Prebble, 1971, pp. 324−325) he chose to come out with the seceders and joined the Free Church, and by the end of that year he was inducted to a charge in Falkirk. There he founded the Garrison Church in 1844 (Falkirk Archives, 2012) and in the course of time two others followed. Having encountered many examples of serious poverty and terrible social deprivation amongst his flock, he was soon labouring to provide schools, of which two were built, and to bring about lasting social change (The Falkirk Wheel, 2011). Having first married Isabella Carruthers who died in 1836, in 1840 he married Catherine Caddell (1817−1890) who was from a family with whom his mother had some connection. Lewis Hay Irving is buried in Camelon cemetery near Falkirk and the present Camelon Irving Memorial Church is named after him.[20]

The next son, Alexander Irving (1813−1882), was a soldier who rose to the rank of major-general in the Royal Artillery. He served in the Crimean War and was appointed a Companion of the Bath (Bell, 1881, p. 5; Henderson & Grierson, 1914).

Archibald Stirling Irving (1816−1852) was born on 18 December 1817, the namesake of a mining manager at Leadhills who is mentioned in the final section of this chapter. Although like his brother John he attended Edinburgh Academy, he had a delicate constitution that left him unsuited to any formal career. Supported by a pension from his father, he lived in various parts of Scotland, drawing on them as inspiration. An avid scholar of the classics and literature, he also wrote many songs and poems which were published anonymously as Original Songs, in two volumes, by the Rev. William Murray (Irving, 1841 ). In the last year of his life he married Helen Laing who cared for him until his death on 29 October 1 851 (Rogers, 1856, pp. 235−236).

David Williamson Irving (1819−1892) may have been named after David Williamson, the judge Lord Balgray. Having been much influenced early in life by his elder brother John, David went with him to Australia where, unlike his brother, he decided to stay. He settled, married, had a successful career, and eventually became a police magistrate in Tamworth, New South Wales (Bell, 1881; Henderson & Grierson, 1914).

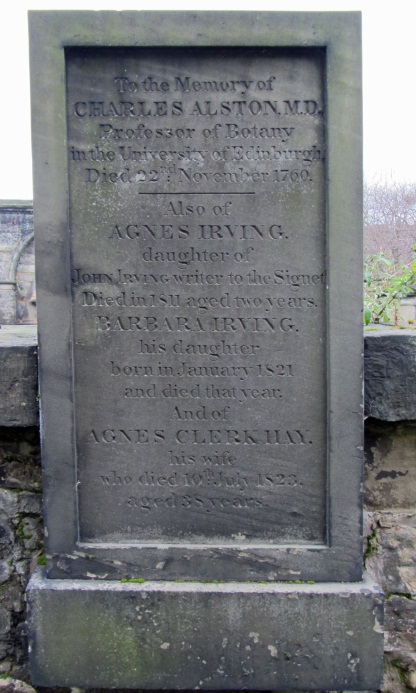

John Irving, the father of these illustrious children, died at about the age of eighty on 26 May 1850. His wife Agnes died long before him in 1823 (Gentleman’s Magazine, 1823, p. 647) and he was buried by her side in the Canongate churchyard. His sons George and Archibald Stirling, who both died in his lifetime, are buried with him. Buried with Agnes are their daughters Barbara and Agnes who both died in infancy. It is curious to note, however, that on Agnes’ headstone, which is clearly the older of the two, the first lines of the inscription are to someone apparently unconnected with the family (Plate 12.4). We shall soon, however, find the connection between the Irvings and the man whose name was given to the genus of trees Alstonia by the botanist Robert Brown (mentioned in Appendix 5 as the discoverer of random ‘Brownian Motion’ in tiny particles).

The memorial to his wife, Agnes Clerk Hay, appears under Dr Alston’s on the right.

John’s memorial also bears inscriptions for his sons George and Archibald Stirling. Buried with their with their mother are daughters Barbara and Agnes, who died in infancy. A surprise is that the stone is headed by a memorial to Dr Thomas Alston, Professor of Botany.

To the Memory of

CHARLES ALSTON M.D.

Professor of Botany

in the University of Edinburgh

Died 22nd November 1760

What is the connection?

12.4 A Case of Multiple Connections

James Clerk Maxwell, James Stirling, John Napier and Sir Isaac Newton: these four great names are connected one to the other by the subject of mathematics, and while two of them were natural philosophers, a different pairing was very interested in metals, specifically lead and gold. On top of that, three of the four were related to each other! However, let us straightaway eliminate the obvious guess that the Irvings of Newton might have some connection with Sir Isaac Newton (1642−1727). While it has been mooted that Alexander Irving named his house near Elvanfoot in honour of the great Sir Isaac, any such claim is specious because, as explained in §11.2, Irving’s estate had been known as Newton long before Sir Isaac came on the scene.

Let us, however, examine other possible connections from Newton himself to the rest of our famous quartet of mathematically orientated geniuses. Apart from being the premier physicist and mathematician of his era, Newton for a time was deeply involved in alchemy (O’Connor & Robertson, 2000). Although the subject is now thoroughly discredited, such ideas were no further from the truth than many other serious scientific ideas of the day, for example, those regarding the basic elements and the principles of medicine. His interests were therefore scientific rather than mystical and his experiments in this area should be seen as early probings in the subject of metallurgy. Given that he was Master of the Royal Mint from 1699 to 1727, any rumours that may have come his way concerning the possibility of creating gold from base metals would have prompted thorough investigation. Metals and mining are, of course, intimately related.

In the early eighteenth century, Newton encountered the much younger James Stirling (1692−1770) (Fraser, 1858, pp. 91−102), the Scottish mathematician who gave us Stirling’s asymptotic approximation for N factorial, the Stirling numbers, and central difference formulae (O’Connor & Robertson, 1998). As a young man, Stirling had travelled to Venice where he discovered the secrets of making Murano glass, and so he was not simply a mathematician, he was also a ‘hands on’ enquirer with a technological bent. Newton would have recognised a common bond with Stirling not only in mathematics but in this sort of early scientific interest. But above all, the young Stirling must have deeply impressed Newton with his work on cubic curves, for in a paper ‘Linae Tertii Ordinis Newtonianae’ published in 1717, he essentially completed Newton’s own efforts on the subject. Despite the age gap, a bond seems to have formed between the men and they became firm friends (Carlyle, 1898).

But where does this get us? In 1734−35, when he was back in his native Scotland, James Stirling undertook some studies on the lead mines around Leadhills where, in 1736, he subsequently took up residence, presumably as some sort of scientific and management consultant to the mine manager. He was then appointed as the manager in 1739, a role in which he proved surprisingly adept (Harvey, 2000). His house at Leadhills, built for him under the architect William Adam[21] by the Scots Mining Company, still stands. Being of a similarly wide-ranging capability as Newton himself, Stirling took to the task in hand with great accomplishment. On his death in 1770, he was succeeded in the post by his nephew Archibald Stirling (1738−1824).[22] Archibald may not have been at the same level of competence as his uncle, for in 1800 Alexander Irving of Newton was appointed to assist him (Waterston & Shearer, 2006). But why did Alexander Irving, then an advocate and Professor of Law, get involved? He had lands in the area of Leadhills, specifically at Shortcleugh, which had mining potential (Harvey, 2000); more than likely, he had invested in the mines and made money out of them when the going was good, and it may even be the case that his father, George Irving, also had some involvement in his time.

Alexander Irving was sole manager of the mines until 1820. Since he was a joint professor of civil law with John Wilde, it could be thought that this latter arrangement would have given him more time to devote to running the mine, but the reason for it was that John Wilde had become unfit for the job, and Alexander had been appointed to the post on the understanding that he was to stand in for Wilde and carry the entire workload of two courses, one on the Institutions and the other on the Pandects.[23]As we have already seen, Scottish professors and judges had virtually six months of the year to attend to their own business, but during the academic term Alexander would have had to rely on correspondence with someone on site upon whom he could rely. When some years later the owners became dissatisfied with their returns, they appointed an assistant for him, John Borron, whose role was ostensibly to support him, but in fact he took over the role completely in 1824. No doubt there was too much on Alexander’s plate to allow him to focus on the job in the single-minded manner that James Stirling had been able to demonstrate.

Alexander Irving, as James Clerk Maxwell’s paternal grandmother’s half-brother, is a connecting link between Maxwell and James Stirling, and as we have already seen, John Irving named one of his sons Archibald Stirling Irving. Nor should we overlook the fact that Stirling was at Leadhills during the time that George Clerk Maxwell and his father the Baron were frequently in the area and in particular, as discussed in §8.13, George Clerk Maxwell and his partners had a tack on land nearby, in fact adjacent to George Irving of Newton’s property of South Shortcleugh. In addition, William Adam, the Baron’s architect for Mavisbank, had built James Stirling’s house at Leadhills. In such a desolate area where mining was the greatest ongoing concern, George Clerk Maxwell, James Stirling and the second George Irving of Newton, must have been at least acquainted with one another. But what is there to suggest that the connection went any further than that?

An examination of Family Trees 4(a) and 4(b) shows that James Stirling and the Baron’s second wife, Janet Inglis, had a common ancestor, James Stirling of Keir (d. 1588). Through the line of Stirling of Garden, James Stirling the mathematician was the fifth generation after James Stirling of Keir by direct descent (Fraser, 1858, pp. 35−44, 91−102). Through the marriage of Marion Stirling, the latter’s daughter, to Sir John Houston of Houston (d.1609), Anne Houston was also his fifth generation descendent, and she was the mother of Janet Inglis, and consequently the grandmother of George Clerk Maxwell. Families such as these knew their lineage intimately, and the Stirlings and the Houstons would have been well acquainted with the details of their interrelationship. Perhaps the surprising thing that arises out of this family tree is that James Stirling of Keir was also John Napier of Merchiston’s father-in-law! Curiously, at the time of their marriage, the Napiers owned Wright’s houses (Grant, c. 1887, vol. 5, pp. 32−34), the property just outside Edinburgh purchased by the first John Clerk of Penicuik about 1650.

There is therefore no real mystery concerning the name of Newton, and any connection between James Clerk Maxwell and Sir Isaac Newton amounts only to the coincidental facts that they both made outstanding advances in fundamental physics; both were fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge; Newton knew James Stirling and, as seems very likely, so did Maxwell’s forbears, George Clerk Maxwell, the Baron and George Irving of Newton.

While it is not impossible that the Baron met Sir Isaac Newton on one of his many visits to London, there is no mention of it in his memoirs. When the Baron was eventually elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1727, Newton had been dead for over six months. In fact, when the Baron first visited Sir Hans Sloane earlier in that year, Sir Hans had only just taken over the presidency from Newton. The Baron had arrived in London ‘about the begining of Aprile’ 1727, coincidentally just a few days after Newton’s death on 31 March. Given the timing, it is possible that the Baron had set out in the expectation of meeting Newton, but if had known Newton at all, he would not have failed to mention it.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

We now return to the curious presence of the name of Dr Charles Alston (1683−1750) on the gravestone of Agnes Clerk Hay, the wife of John Irving. A professor of botany at the University, Alston also held the associated post of curator of the Edinburgh Physick Garden.[24] (Fletcher & Brown, 1970, p. Ch. 5; Allen, 2015) The reason his memorial is above that of Agnes Clerk Hay lies in the fact that John Irving’s mother, Mary Chancellor, was related on her own mother’s side to the family of Birnie of Broomhill (see Jean/Mary Birnie on Family Tree 6). Two generations earlier, Elizabeth Birnie had married Thomas Kirkaldie, and Charles Alston was their grandson, making him John Irving’s second cousin twice removed. An additional link was formed in 1741 when Dr Alston married his second wife, Bethia Birnie, who was John Irving’s great aunt. Although John’s and Agnes’ gravestones are of matching design, Agnes’ stone is clearly much older, and so it is possible that it stood there for fifty years with only Charles Alston’s name on it before the first of the Irvings’ children was interred. Perhaps John Irving had inherited the lair, or by some other means managed to acquire the rights to it for his own family’s use. Death was a frequent visitor, and burial space was in short supply.

If there is any disappointment at there being no familial connections with Isaac Newton, at least we have serendipitously found that James Clerk Maxwell and Professor Charles Alston MD share a common ancestor, the Reverend Robert Birnie (1608−1690).[25] That Maxwell was also related to the mathematicians John Napier of Merchiston and James Stirling through the Baron’s mother-in-law seems quite incredible!

Notes

[1] See Figure 1.1 and Plate 8.3. It was drained between 1759-63 (Royal Scottish Geographical Society, ‘Images for All: Edinburgh 1773’ available at https://www.geos.ed.ac.uk/~rsgs/ifa/gems/maped1773.html)

[2] This may be hard to make out nowadays simply because many of the original First New Town houses were remodelled or obliterated in later developments. Nevertheless, if one looks very carefully in the First New Town, some of these more modest original structures built between 1777–1799 can still be seen.

[3] Canonmills is about a quarter-mile north Heriot Row where it crosses Dundas Street, whereas Bearsford Park was in the area of Queen Street Gardens to the south of Heriot Row

[4] The procurement of the required land had to be preceded by an act of Parliament that allowed the expansion of the Royalty, i.e. the Burgh, of Edinburgh northwards by means of taking in extensive lands belonging to Heriot’s Hospital, then an orphanage within the walls of the Burgh but now a private school. It had been endowed in 1617 by George Heriot, a very wealthy man who had been goldsmith and, in practice, banker to King James VI, earning himself the soubriquet of ‘Jinglin’ Geordie’, implying that he had so much gold about his person that he jingled as he went. In the process, he acquired much property throughout and around the town which he later bequeathed for good purposes. When Henry Mackenzie, author of Man of Feeling, was living at number 6 Heriot Row (in the present numbering system), he recalled the land as it had been before the new houses were started in 1800; he had shot snipe there in the fields of Wood’s farm lying between Canonmills and Bearsford Park.

[5] SOPR: Deaths 685/010 0970 0289

[6] She is given as Janet by (Irving M, 1907) but on their registered marriage articles (GGD56(unsorted) Extract Marriage Articles, 1788) she is Isobel or Isobell, and on John Clerk Maxwell’s family tree (DGA: RGD56/13) she is given under the alternative form, Isabella.

[7] He was one of the Colquhouns of Camstraden (Fraser, 1869, p. 194) near Luss on Loch Lomond, home of Clan Colquhoun. John Clerk Maxwell’s family tree (DGA: RGD56/13) has his father as being a Glasgow merchant, but he mistakes Camstraden as being Garscaden, a different branch of the family.

[8] Coincidentally the same name as the Baron John Clerk’s wife. She was daughter of Thomas Inglis, a merchant or pewterer (or both) in Edinburgh. The Baron’s wife was daughter of James Inglis of Crammond.

[9] A Scottish judge’s formal title was actually ‘Senator of the College of Justice’. There had been a previous Lord Newton, Charles Hay, but they were not related.

[10] Irving (1907) gives 1773-1850.

[11] They had only one child, a son, by whom they had a grandson Sir Henry Turner Irving GCMG (1833–1923) who was a three times a colonial governor. His last posting was as Governor of British Guiana, where he took a strong stance as a reformer in the face of strong vested interests amongst the planters.

[12] ‘I wrote to Irving before leaving Kelso. Poor fellow, I am sure his sister’s death must have hurt him much; though he makes no noise about feelings, yet still streams always run deepest,’ from a letter to William Clerk, 26 August 1791 (Lockhart, 1837i, p. 110)

[13] No such placename as Partraith has been found, but it may be connected with the Potrail Water, one of the main tributaries of the Daer Water that flows into the Clyde at Newton.

[14] 1773 was the first year in which there was a directory, and it was not fully subscribed and so the fact that there is no entry in that year for either George or Thomas is not very significant. There were no further directories in George’s lifetime.

[15] When Mrs Irving of Newton departed 27 Heriot Row in 1842, a Lt. Col. Morrieson was its next occupant. In one of those ever-so-curious twists that our story seems so fond of taking, Col. Morrieson’s wife and stepsons soon take a significant role in our story. For, just four doors along, at number 31, was where the ten year old James Clerk Maxwell had been installed, during term time, in the care of his Aunt Isabella. At school, James met Lewis Campbell, who had been attending Edinburgh Academy since 1840 and was in the year above. By 1845, Lewis’ widowed mother Eliza Campbell had remarried, to Lt. Col. Morrieson, and so he now lived at 27 Heriot Row, practically next door to James. In this way, therefore, the boys became not just school acquaintances but lifelong friends. See also §2.2 and §16.1

[16] According to Lord Cockburn (1874, vol. 1, pp. 26–7), ‘No man ever rose so much above expectation after being made a judge.’ He did not have sufficient force of personality to hold sway amongst other judges in great cases, but:

… in civil causes, deciding by written leisurely judgments, he was perfect … great knowledge of law, general intelligence, especially in science, a laborious patient manner, admirable listening, only broken by short judicious interrogations, perfect serenity, complete candour, and a devotion to his business …

[17] In a breach of the conventions that have been observed so far, Alexander chose to give his son George a middle name. Vere is an early spelling of Weir, recalling the origins of Newton.

[18] It is also evident from Lockhart’s Life of Scott that the Irving and Scott families lived fairly close to one another.

[19] To be fair, the engines were relatively small and capable of propelling the ship, via a screw, at something less than 4 knots, which would have been quite ineffective in pack ice. The main idea at the time was to give the ship a means of propulsion when it was becalmed. Both ships had seen prior service in the Antarctic.

[20] SCAN: Record GB558/CH3/1574

[21] The same William Adam that built Mavisbank for Baron Sir John Clerk during 1723–27 (q.v.), and was father-in-law of the Baron’s son, John Clerk of Eldin.

[22] After whom we presume Archibald Stirling Irving, son of John and Agnes Irving, was named (§12.3).

[23] Grant (1884, pp. 365–6) The pandects comprise key excerpts from Roman Law.

[24] Curiously, Dr Alston’s immediate predecessor at the Physick Garden, Dr William Arthur (Fletcher & Brown, 1970, Ch. 3) was the second husband of Baron Sir John Clerk’s sister Barbara. Arthur fled his post after being involved in a Jacobite plot in 1715.

[25] Since Mary Chancellor was George Irving’s second wife, there is no biological link unless, of course, there was some prior link between the Chancellors and the Irvings, for example through the Birnies.