Brilliant Lives

By John W. Arthur

Second edition

Published by the author in 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © John W. Arthur 2016, 2024

All rights reserved.

Contents

10.1 Sir James Clerk, 3rd Baronet

10.5 William Clerk (and Sir Walter Scott

10.6 Lieutenant James Clerk RN

10 The Clerks of Eldin and Other Notable Clerks

Thus far we have traced the Clerk line from the first Clerk of Penicuik down to the Baron, Sir John Clerk, 2nd Baronet of Penicuik and his brother William Clerk, whose respective children George and Dorothea began the Clerk Maxwell line. From George and Dorothea, we passed directly on to their sons, Captain John Clerk RN, who succeeded his father as the 5th Baronet of Penicuik, and Captain James Clerk HEICS, who was briefly heir to his mother’s estate of Middlebie. However, we have not yet mentioned George’s elder brother James who, as the 3rd Baronet, was his predecessor at Penicuik. Nor have we mentioned the family of the Barons’ youngest surviving half-brother, John Clerk of Eldin. We now seek to remedy the situation by saying something of the 3rd Baronet and the most notable of the Clerks of Eldin. We also make brief mention of the related Clerks of Rattray, wherein there was a second Baron of the Exchequer, and finally we return to the story of Isabella Clerk, third surviving child of James Clerk HEICS and Janet Irving, for it was she, as Mrs Wedderburn, who took her nephew James Clerk Maxwell into her home at 31 Heriot Row from 1831 to 1847.

10.1 Sir James Clerk, 3rd Baronet

Having remarried in February of 1709 to Janet Inglis, the Baron’s first son by his new wife was born on 2 December of the same year and was named James after Janet’s father, Sir James Inglis of Cramond (BJC, p. 2). He was the Baron’s second son, the first being the child’s half-brother John from the Baron’s first marriage, almost exactly eight years his elder. We learn this, and much of what little we know of James’ childhood, from the Baron’s memoirs. He tells us that just about James’ fourth birthday:

… my third son Hary … was a very strong healfull [sic] Boy as ever I saw in my Life, whereas his elder Brother James was very tender from birth, and continued so till he was 4 or 5 years of Age. (BJC, pp. 85−86)

Sadly, Harry (Henry) died of smallpox, and so it had very much surprised the Baron and his wife that the comparatively weaker James not only survived but was their only child not to catch the full disease, escaping with just some sores and boils. Once again the Baron mentions his son’s frail disposition:

We were in great anxiety about him, because of his weak constitution and bad habit of body… (BJC, p. 86)

Despite his apparent frailty, not only did he survive, his boils and sores were cured when he took smallpox proper just over a year later.

Perhaps one of James’ earliest introductions to the world of antiquities was when, at the age of fourteen, he was allowed to accompany his father and his antiquarian friend, Alexander Gordon,[1] on a trip to see Hadrian’s Wall in the spring of 1724 (BJC, p.117). However, we hear nothing more of him from the Baron until seven years later, when he set out for Holland to follow in his father’s footsteps as a student completing his studies and making the grand tour (BJC, pp. 138−139). Nevertheless, we do know that James had previously been sent to Dalkeith grammar school (note 2 of Chapter 8), for the Baron received a letter concerning James’ future education from William Simpson, schoolmaster there.[2] It must have been a satisfactory institution, for his younger brothers George and John were sent to the same school in due course.

James may then have attended Edinburgh University, but if so, he did as many others did and left without graduating (Laing, 1858). In 1729, he enrolled in St Luke’s Drawing School[3] where he would have made connections with other young artists of his day. Nevertheless, the intention seems to have been that he should become an advocate, for it was with that aim he set out for Holland in April 1731, travelling first with his uncle Robert to London, where he stayed for several months. He then headed for Leiden in the following October; once there, however, he did not find the study of law as much to his taste as his father had hoped. Having stuck it for only one year, his failure to obtain a satisfactory result seems to have occasioned an appeal made on his behalf to the Lords of Council and Session, requesting that he be admitted as an advocate.[4] The attempt must have been in vain because he does not appear in the Scottish Record Society’s publication of those who were admitted (Grant, 1944).

In the years that followed, James travelled about Europe looking for paintings and music to study and to buy, much of which was sent back to Penicuik for his father, including works by Rubens, Rembrandt and Poussin. In January 1736 he was joined in Leiden by his brother George who was belatedly beginning his studies there (Chapter 8), and when George had completed his first year he begged leave of his father to make a tour of Germany with James before he returned in the summer of 1737.[5] But James could not be persuaded to return along with George and stayed on in Europe for another two years, soaking up as much European art and refinement as he could.

It was just as his father had done many years before. The Baron, however, was against it because of the likely expense (BJC, p. 146, marginal notes), for he knew only too well how much debt he had racked up during his own time abroad. He also felt his son, having reached the age of twenty-eight, was letting time slip by. James, on the other hand, was having the time of his life. Nevertheless, in 1738 and 1739 he also found time to study the process used by the Dutch for bleaching linen,[6] which may have been done with the idea of helping George in setting up his linen factory at Dumfries.

In October 1739 he at last returned, much to his parents’ relief and delight, and his father was further pleased to observe that, despite his long sojourn in Europe and the extent to which he had embraced all that he had found there, his head had not been turned against his native land (BJC, p. 154). Within two years, however, James was off again, ostensibly to London. But it seems that he already had a different plan in mind, for once there he wrote home begging leave to go again to Europe, saying he wanted to observe the election of a new emperor at Frankfurt (BJC, p. 163). His father protested, knowing that he could not really do much to prevent James from going, before at last consenting.

James stayed on in Europe, and having spent something close to a third of his life abroad, set off for home only when he caught wind of the impending Jacobite uprising in 1745. James’ first thought on his return was to enlist in the King’s army, and so when he reached London he obtained some letters of recommendation to help get him a commission (BJC, p. 192). The Baron knew well that despite his two eldest sons’ eagerness to fight for King and country, they had not been bred to military life. He had managed to channel George’s enthusiasm towards taking up with a private regiment, the Royal Hunters (Chapter 8), which engaged in supporting roles, such as scouting and acting as guides. But he was more concerned about James, and when at last he met up with him at Durham, where he was taking refuge from the invading Highland army with his wife and eldest daughter (see §4.7), he managed to put him off the idea completely and encouraged him instead to make his way back to Scotland to ‘help the people in our country’. The Baron told George, then at Morpeth, by a letter of 3 November 1745:

… I suppose you have seen James. I wish he wou’d go on to Berwick, for he is not a case to be one of your Hunters (Prevost, 1963, p. 238, my emphasis)

As to what James actually did when he got back to Scotland, we know only that he was present, though not a participant, at the battle of Falkirk Muir on 17 January 1746, when the King’s army was shamefully and unexpectedly routed by the rebels; many of its soldiers fled the field without even engaging the enemy. Although the Baron tells us many details, he merely mentions in a marginal note, which he added sometime later,

N.B. – There were thousands of onlookers who did great harm, for as they came not there to fight, they ran off amongst the first, and came directly to Edin. However, my son James, who was there, continued till our army retired. (BJC, p. 195)

These spectators had gone in expectation of seeing the Jacobites defeated. But, because he makes no mention of James in the main narrative, no mention of any regiment that he was with, nor any other role that he might have been undertaking in any sort of supporting capacity, there is no question that the Baron means that James was with the spectators rather than the army – which was as only as far as his father wished him to go. Unfortunately, Grant states misleadingly in his introduction (BJC, p. xix), ‘but his second son, George, served in the royal army, and James, his eldest son, fought bravely at Falkirk’. If the reference to George here is only mildly inaccurate, the part about James seems quite adrift and is no doubt a misconstrual of the Baron’s note.

The last battle of the rebellion, indeed the last pitched battle to take place in the United Kingdom, took place three months later at Culloden Moor, much to the relief of the Baron and his family. The Baron was now seventy years of age and experiencing further decline not only in his health but also his vitality; he therefore began to think about the day when he would no longer be there to take charge of affairs. In 1748 he had discussions with James about the succession, showing him the family accounts and papers so that he would be adequately prepared when the time came.[7] While the Baron was still far from retired from the management of his affairs and his projects on the estate, by 1750 he had come to the realisation that there were things he could no longer satisfactorily cope with:

… I found my self very ill used by some whom I trusted at Lonhead in the management of my Coal affaires, therefor I put them in the hands of my son James, who had more strength of Body and more leisure to look after them … Besides, as to the choise of my son for chief Manadger, there was a necessity to breed him up a little in the management of these matters. This experiment I found succeeded to my Wishes, for the profits of my coal began to be doubled. (BJC, p. 225)

It therefore seems that James was more than just a lover of the arts and a gentleman of leisure, and that he proved adept at the practical affairs of business. the Baron had built Mavisbank so that he could be close to his coal workings (see §4.8) but the last time that he mentions being there with his family is in December of that year. Although there is no explicit mention of it, it would seem natural that James would now have lived at Mavisbank so that he could be the one on hand to see that things ran smoothly in the mines, which they did. In 1753, the Baron went further, in allowing James to add some rooms onto the west side of his principal residence, Newbiggin, including a library (BJC, p. 228). All the same, he mentions ‘as there was no pressing occasion for these things, the work proceeded slowly’, which is tantamount to saying that, in spite of his agreement and in spite of his son having greatly improved his coal revenues, he did not see any urgent need to spend money on them.

By the age of seventy-eight the Baron was feeling his age. He wrote in his journal:

… I observe a great decay of bodily strength and of my memory, yet I endeavour to keep a good heart and to bear with patience and resignation what I cannot help. (BJC, p. 228)

By then he would have been sure that he had accomplished everything that needed to be done to pass on Penicuik and the Baronetcy to James. He died in the following year, on 4 October 1755, upon which James became the 3rd Baronet of Penicuik:

After about a month as the new Baronet, and no doubt having taken the opportunity to review his new situation and his future options, Sir James decided to go and live in Edinburgh for a while.[8] His father had referred to living in Edinburgh, when it was convenient to do so, at his house there in Blackfriars Wynd (see note 5 of Chapter 4). There is mention of Sir James having also lived there at about this time, or at Sempill’s House off the north side of Castlehill.[9] Unlike his father, he did not have reason to be in Edinburgh because of any office that he had to attend to and so, for a man of his tastes, the reason must have been social, perhaps the opportunity of finding likeminded company, or perhaps even a wife. Had the Baron already sorted out a match for James during his lifetime, he would have been sure to mention something of such import in his memoirs. It therefore appears that even on entering his late forties James had not yet found a life partner. He did eventually marry Elizabeth Cleghorn (d. 1786?), daughter of Rev. John Cleghorn (Anderson, 1878), who until his death in 1744 had been minister at Wemyss in Fife,[10] but no record or other particulars of his marriage has been discovered.

In the years immediately following his father’s death, James attended to family affairs, such as discharging his father’s bequests, providing an annuity for his mother and a bond of provision for his brother John, and helping his brother Adam get a commission in the Navy.[11] At Penicuik he made few changes while his mother was still alive, save for the erection of a monument to Allan Ramsay, a longstanding family friend, who died in January 1758; an obelisk, no doubt to Sir James’ own design, was erected at a high spot near Ravensneuk, on the south-east of the estate in 1759 (BJC p. 229n1; Wilson, 1891, pp. 154−155).

At the end of January 1760, just shortly after his own fiftieth birthday, Sir James’ mother, Janet Inglis, died (Foster, 1884, p. 50). James now felt free to ring the changes at Penicuik (Penicuik House Project, 2014b). He designed for himself a new main residence and stable block[12] and began their construction with the aid of the builder John Baxter snr, the stonemason who had constructed Mavisbank for the Baron. At first Sir James’ intention was to remodel Newbiggin, the old family house, but he soon gave up the idea and tore it down, perhaps to the regret of his brothers and sisters; they simply had to accept that the prerogative was his alone. Sir James’ cousin, Colonel Robert Clerk,[13] offered his opinion on Sir James’ design, and drew up some notes criticising it and proposing alterations (Thom, 2014, p. 121; Penicuik House Project, 2014a). Not only did he do that, he also sent a copy to the architect Robert Adam, son of William Adam who had worked with the Baron, and was now also Sir James’ brother-in-law.[14] Robert Adam apparently agreed with the Colonel, but Sir James had been assiduous in developing his aesthetic acumen and would not have his ideas and desires dismissed as being idiosyncratic. He would again have his own way.

John Baxter snr turned Sir James’ original drawings for the house into detailed plans, and in 1762 work began in earnest, using 200,000 bricks ordered for the project[15] and materials recycled from the now demolished Newbiggin. To help finance the project, in July 1763 Mavisbank was sold to a cousin, another Robert Clerk.[16] Meanwhile, Sir James was helping to support John Baxter jnr (Skempton, 2002), the builder’s son, and Alexander Runciman (1736−1785), then a fledgling artist, who were both studying in Italy. While John Baxter jnr was in Rome, Sir James wrote asking him to commission copies of three statues suitable for Penicuik. Baxter sent him sketches of four to choose from: the Medici Apollo, the Borghese Faun, the Apollo Belvedere and the Campidoglio (or Capitoline) Antinous.[17]

According to Jackson (1833, pp. 341−342), Runciman had been one of the ‘apprentice painter-boys’ working on the new house who had executed the paintings under the colonnade at Penicuik House, so much to Sir James Clerk’s satisfaction, that he sent him to Rome, at his own expense, to complete his professional studies.

Sir James’ patronage of Runciman is confirmed in letters, including those he received from Runciman himself when in Rome, concerning the direction of his studies;[18] after informing his patron that he had finished a particular picture, in one such letter Runciman asked for an advance so that he could do even more. However, he did make clear that he was not seeking ‘pecuniary advantage’ and, on the contrary, ‘my ambition is to be a great painter rather than a rich one’.[19]

When Runciman returned from Rome in 1772, Sir James commissioned him to decorate the interior of the house, which had been structurally completed by 1769. His initial idea was to have him paint the ceiling panels of the main drawing room with themes from the Baths of Titus, but he changed his mind to have it done in themes inspired by The Works of Ossian, a ‘translation’ of ancient Gaelic mythology[20] that had been fabricated by the Scottish poet James McPherson (1736−1796) and published during 1761−65. Although the authenticity of the work was challenged, the ‘discovery’ of an ancient Gaelic mythology caused a sensation amongst the devotees of classical romantic tales and epic poetry, and it is clear that Sir James had been one of them. His great drawing room thence became known as ‘Ossian’s Hall’.

While work was progressing on the house, it was also progressing on the stable block, which is notable for the full-size replica of Arthur’s O’on[21] that was erected as a dovecot forming the centrepiece of its rear elevation. James’ father, the Baron, had much admired the original, an almost intact Roman temple, and declared, ‘I wish I could have redeemed it at the expence of 1000 guineas’ (BJC, p. xxvi). While the replica, built as per the drawings of the monument recorded by Gordon (1726), was Sir James’ touching memorial to his late father, from an architectural standpoint it looks at odds with the tall spire that dominates the front elevation of the building. He was clearly more taken with the notion of recreating the O’on than sticking to classically proportioned shapes based on straight lines and circles.

In all, it seems that Sir James had the financial wherewithal to complete his grand design and to decorate and furnish it in equally grand style within more or less ten years. During the time of its building, Sir James also got involved with John Baxter snr in submitting designs for Edinburgh’s North Bridge, which provided the first convenient link from the Old Town to the New by spanning the chasm across the head of the Nor’ Loch between the High Street and the site of the new Register House.[22] He even sent to John Baxter jnr, who was then studying in Rome, a request for a bridge design in the style of a Roman viaduct. It was, however, William Mylne (Skempton, 2002) who won the contract to build the bridge to a design of James Craig, architect of the New Town. There was much ado in 1769 when part of this bridge collapsed during its construction and killed five people; the bridge was too narrow for modern use, and was consequently demolished in 1896 to make way for the present one.

After Penicuik House and its stable block, Sir James turned his attention to the village of Penicuik itself, which was then very small, and created a new design around a spacious elongated ‘square’, at the far east corner of which was to be a new kirk:

… about the year 1770, Sir James Clerk … planned and laid out a portion of the village as it now stands, giving at the same time pecuniary assistance towards the erection of not a few of the buildings. He also induced a doctor to settle in it, building him a house to dwell in, and providing a large park to graze his horse in the summer. (Wilson, 1891, p. 10)

After giving the schoolmaster notice to quit his property to make way for the development, the foundation of the new St Mungo’s was laid in August 1770.[23] The ruins of the simple rubble-built old kirk still stand in the kirkyard a little to the east, midway between the Clerk family mausoleum and the new kirk. The old and new represent a complete contrast in ideas of what a church should be; small though the new church is, its design is fit for a much grander purpose. Sir James clearly could not resist the classical Graeco-Roman design with portico (St Mungo’s, 2013), just the thing that Robert Adam and Colonel Robert Clerk had criticised in the design of Penicuik House, and which Sir James had so staunchly defended (Penicuik House Project, 2014a).

In 1772, Sir James Colquhoun of Luss, Bt (Collins, 1806) commenced the building of a house at Rossdhu for his new family seat on the west shore of Loch Lomond.[24] He had asked Sir James’ advice on the design, which has some features similar to those of Penicuik House, including the raised portico. Indeed, James is attributed as being the architect, with John Baxter jnr as the builder.[25] Elsewhere it is suggested that there were inputs from Robert Adam (The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2013b. ‘Rossdhu’), but if so, either they did not concern the portico or Adam had now deferred to Sir James on the subject!

If the 3rd Baronet spent lavishly to satisfy his own aesthetic aspirations, he was, like his father, a philanthropist who assisted his protégés, tenants and employees. Not only had he given money for the rebuilding of Penicuik and its church, he acted with all due care by providing financial assistance for rehousing those that were displaced. In particular, his treatment of the old schoolmaster was compassionate, for he gave him a present of a new house and yard (Wilson, 1891, p. 57). Having inherited his father’s coal mines, he did not do as many a laird would have done and simply reaped the financial benefits, he became involved in trying to help his miners, who as a class were then treated as little more than indentured slaves. He interceded when they got into trouble and, in 1772, he even went so far as to write to the Committee of Coal Masters in favour of the abolition of the iniquitous practice of bonding miners to their employment.[26]

Fine tastes in art and architecture and long sojourns abroad apparently did not spoil Sir James’ love of Scottish ways and simple fare. Jackson (1833, p. 342) recounts an anecdote in which Sir James was visited at the newly finished Penicuik House by Henry Dundas, later Viscount Melville, whose statue now stands atop the lofty column in St Andrew Square, Edinburgh. Dundas was seeking Sir James’ vote in the forthcoming parliamentary election, but as Sir James did not know the man well he decided to put him to the test by serving up nothing more than porridge for dinner. Dundas was unabashed by his frugal repast, and thereby gained Sir James’ vote by demonstrating that he was a man who appreciated ordinary Scottish values; of course, the anecdote is meant to reflect that the same quality applied equally well to Sir James.

In 1781, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, which had been formed just the year before, made Sir James a fellow.[27] Clearly he had been forgiven for demolishing Newbiggin, perhaps on account of his recreation of Arthur’s O’on?

As we have already seen, Sir James’ younger brother George Clerk Maxwell was involved in lead mining at Craigton on the Solway coast. While James took no active part in George’s mining company, he did take on a financial interest. George no doubt persuaded him that in time he would get a good return for his money and so they borrowed jointly from the Bank of Scotland to finance George in his enterprises (see §8.13). Between Sir James spending a great deal of money on his building projects and lavish furnishings for his house, and George investing in such things as the Forth and Clyde Canal, prospecting, and the eventual lead mine at Craigton, they both had racked up a fair amount of debt between them. As we already know, by 1781 things had gone badly wrong with George’s mining ventures, and the debts were substantial. In 1782, when Sir James was seventy-two years of age and probably quite ill, the two men agreed that in the interests of paying the external creditors, the debts between them would have to be put to one side and Dumcrieff and Middlebie would have to go. Did Sir James have some inkling that, even if this was a hard cross for George to bear, it would not be long before his brother would inherit Penicuik? George’s own health was also deteriorating, and so they may have appreciated that it would all sort itself out soon enough, and the key thing was to preserve Penicuik for the heirs. In the meantime, George would still be left with the other properties that came under the Middlebie entail, at Dumfries and Nether Corsock, in right of his wife Dorothea.

The possibility that George would soon enough come into the baronetcy of Penicuik came to pass within a twelvemonth:

Sir James Clerk Baronet of Penicuik died at Leith whether he had gone for the recovery of his health upon the 6th day of February 1783 at 4 o’clock in the morning and was interred in the burying ground belonging to the family in the church yard of Pennycuik on 10th day of the said month.[28]

George then became the 4th Baronet of Penicuik, as Sir George Clerk, notwithstanding the condition in the Middlebie entail that required him, as Dorothea’s husband, to hold to the name Maxwell. The validity of his juggling with the names of Clerk and Clerk Maxwell had in any case never come to any legal test. Sir James’ widow, Elizabeth Cleghorn, lived thereafter in Edinburgh at Dickson’s Close until her death, apparently in March 1786. She appears as the Dowager Lady Clerk in only one edition of the Edinburgh directory (1784−86), which is consistent both with the time of her husband’s death and the date believed to be of her own.

10.2 Mathew Clerk

Mathew Clerk was the fith son of Baron Sir John Clerk and his second wife, Janet Inglis (see §4.6). The Baron tells us not a great deal about him, except from informing us:

In Aprile and May 1746 my son Mathew fell ill of a Feaver at Dalkieth… (BJC, p204)

and so we may surmise Dalkeith is where he was sent to school. The marginal note adds:

This boy is a fine schollar, and of great application to learning and business of all kinds.

After his schooling he studied mathematics[29] in the hope of training as an officer in the army, and the indications are that in 1751 he went to Woolwich Military College,[30] during which time his father was making enquiries getting him a commission[31] By the spring of 1757 the Seven Years War was well under way and Mathew, now a junior officer, was making preparations to go with his regiment to fight in America[32] but by the end of the year he was writing home from New York to say things were not going so well ‘we have been extremely unlucky in our expedition’[33] Only days thereafter he received his commission as a sub-engineer with the rank of Lieutenant,[34] and by April he is hopeful again, writing to his mother ‘by the time you receive this we must have struck some blow in America’.[35] In July came the battle of Fort Carillion at the Siege of Ticonderoga (McCulloch, 2008; Nester, 2008) and in the days before the battle Mathew was involved in surveying and reporting on the French defences. It seems that, owing to his inexperience, he did not appreciate that the French had disguised them so that the area looked only lightly defended, whereas in reality the very contrary was true. The battle took place on 8July, and Mathew was one of the many British soldiers that lost their lives in the ensuing defeat.[36]

Having perished soon after the battle and so being denied the opportunity of giving his own account, Mathew Clerk was made a scapegoat for the failure of the attack by his superior officer, Captain Abercromby, who maintained that Clerk had grossly underestimated the French defences. Captain Abercromby, on the other hand, had been rash in his own decision making and had not taken due heed of Clerk’s lack of experience.[37] Typically, Abercromby went on to become a general. A great deal of research has been done on who was more to blame; see for example Nester (2008) and Kingsley & Alexander (2008), while McCulloch (2008) gives a strong rebuttal of Kingsley & Alexander.

10.3 John Clerk of Eldin

John Clerk of Eldin (1728-1812) [38] was the second youngest son of Sir John Clerk, the Baron, and the younger brother of James and George, who were respectively the 3rd and 4th Baronets of Penicuik. But the appendage ‘of Eldin’ did not come to this John Clerk by inheritance, it came as a result of a small estate he purchased largely by the fruits of his own labour. Now part of a housing estate in Bonnyrigg Midlothian, it was near Lasswade, on the River North Esk more or less equidistant from Edinburgh and Penicuik. He was connected to the Adam family by his marriage to Susannah, sister of the architects John and Robert Adam. As previously noted, their father, William Adam, had been architect to the Baron for the building of Mavisbank. John and Susannah’s eldest son, also named John, was to become famed as one of the most notable advocates of his time, a ferocious cross examiner and scathing wit who later sat on the bench as Lord Eldin, Another son William, a lawyer and Clerk of the Jury Court, was a particularly close friend of Sir Walter Scott. He was also renowned for his wit and barbed tongue but, in contrast to his brother, he preferred to lead the life of a gentleman, frequently attending dinners that he would seek to enliven with clever remarks (Grant, pp. 70-90, 170). There was also a third son, James, who joined the navy and we will hear more of these brothers in the ensuing sections of this chapter.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, there were three Clerks who were sailors, this James Clerk and his two cousins John and James Clerk, both sons of George Clerk Maxwell (see §10.6). We therefore have to be careful to distinguish not only between these three gentlemen, but between his father, John Clerk of Eldin and his brother John Clerk, Lord Eldin.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

The fifth surviving son of the Baron and Janet Inglis was born on 10 December 1728 and named John in memory of the Baron’s first son of that name, his only child by his first wife Lady Margaret Stewart, who had died in 1722. Like his older brothers James and George, John was sent to the grammar school at Dalkeith (see §8.2), going thereafter to Edinburgh University where, it is said, he attended the anatomy classes of Prof Alexander Munro along with James Hutton (Bertram, 2012b). The Baron apparently thought his son had the makings of surgeon but, whereas Hutton later qualified as a doctor, John Clerk did not stay the course. Like his older brother George he had a bent for practical things, while like James he had a talent for art and, in particular, drawing. Having befriended Robert Adam and Paul Sandby,[39] as young men the three would often spend time together drawing local lanscapes. The friendship with Adam led to him marrying Adam’s youngest sister, Susannah, in 1753, while the friendship with Sandby led to him taking an interest in etching, which he was to take up as a gifted amateur

As a fifth son, however, the young John Clerk was too far down the pecking order to get a really substantial hand-out from his father to set him up in life. He had a privileged upbringing and had been given a decent education, but in the main he had to find his own way in the world. But perhaps it was also the case that the Baron had also realised that he had made a mistake with George in making things too easy for him, for example, by sorting out the affairs of Middlebie and giving him Dumcrieff outright for George was now heading back to Edinburgh having experienced his first financial failure, the linen factory at Dumfries.

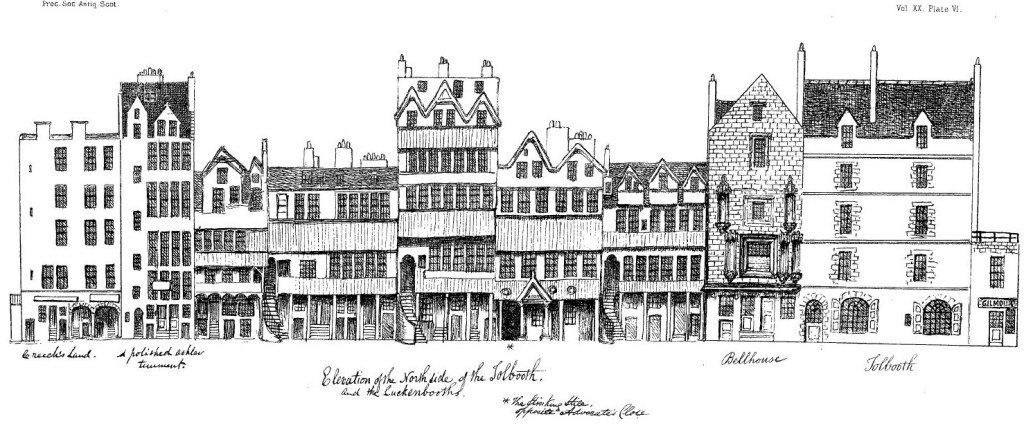

It was John’s lot to be a merchant, and no doubt the Baron went so far as to use his connexions and an advance of money to set up his son in business. To trade as a merchant in Edinburgh or other recognised burgh, it was necessary to have a burgess ticket. The usual way of achieving this would be to serve an apprenticeship following which, if one worked hard enough and could demonstrate the wherewithal to set up on one’s own, admission as a burgess and guild brother could be obtained. For example, this was the route, whereby Allan Ramsay senior had been able to set up as a wigmaker (see §5.1). John Clerk, however, seems not to have undertaken such an apprenticeship, for there is no mention of him in Boog Watson (1929), and he was only 22 when he gained his burgess ticket in July 1751. While he was entitled to do so in right of his father, the fact that the Baron had taken out his burgess ticket just the week before is clear evidence of a helping hand.[40] He was set up in a partnership with Alexander Scott trading in the Luckenbooths,[41] a set of shops in a long block of tenements that since 1440 had occupied the centre of Edinburgh’s High Street close by the then north wall of St Giles Kirk (Figure 10.1). Scott and Clerk seem to have been in the business of selling cloth and clothing at the Luckenbooths[42]

* marks the entry called ‘The Stinking Style’ which leads through to St Giles Kirk and directly faces Advocates Close on the north side of the street.

Based on plates V and VII by John Syme as they appear in Miller (1855‒56)

Bertram also tells us that Clerk continued there until 1762, but afterwards he traded further afield, being at Campbeltown during 1769 and Aberdeen during 1771. However, the Clerks seemed almost to collect burgess tickets,[43] most likely because they conferred on them rights which could usefully be exploited in ways other than just trading in the towns concerned. For example:

Mr Clerk was returned as a Ruling Elder for the borough of Inverurie in the Presbytery of Garioch, from the years 1763 to 1784. From the first date till 1772 he is designated ‘Mr John Clerk, Merchant in Edinburgh; (Clerk of Eldin & Laing, 1855)

Therefore, despite these other burgess tickets John Clerk was still trading with Edinburgh as his principal base. Campbeltown and Montrose, for example, were both places of commercial importance. Campbeltown had access to much coal which by the middle of the eighteenth century was being used as fuel for the distillation whisky and for the evaporation of sea water to make salt, while Montrose was a wealthy trading port bringing in timber and flax from the Baltic, and salt wines and fruit from France and Portugal.[44] Given that the burgess and guild system operated on the basis of trade restrictions which determined who could deal in what commodities or ply certain trades, it can be seen why these burgess tickets could have been an advantage. Moreover, John Clerk’s elder brother, George Clerk Maxwell, was in an excellent position to get to know just where the best commercial opportunities in Scotland were, for not only was he by this time a Trustee for the Board of Manufactures and a Commissioner for the Forfeited Estates, he was also a Commissioner for Customs (see Chapter 8). It would have been surprising if George had not thought to mention any business opportunities that he felt would benefit his brothers.

Lithograph, published 1855.

© National Portrait Gallery, London. Reference Collection NPG D33429

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

Whatever John Clerk’s involvement was with other towns in Scotland, it must have contributed to his success, for in 1762 he and Alexander Scott purchased a half share each in a coalfield at Pendreich,[45] on the opposite bank of the river North Esk from the Loanhead mine belonging to his brother Sir James. Nevertheless, this was merely another string to his bow and he did not give up his business in the Luckenbooths till 1772. Having done so, in the year following he bought a nearby estate which he called Eldin (Clerk of Eldin & Laing, 1855).[46] Although it was not an estate on any grand scale, it did allow him the dignity of being referred to as John Clerk of Eldin, Esq. and it would seem that he had been able to buy Eldin from the fruit of his labours rather than out of any gift, inheritance or windfall. Having purchased his estate, however, his principal residence was still Edinburgh. In the 1774‒5 Edinburgh Directory, his house is listed as being at ‘the back of the theatre’, that is to say, behind the Theatre Royal just off the north east corner of the North Bridge. In the late 1760’s, tenements had been built there so as to enclose a square with the theatre, opened in 1769, along its northern edge. John Clerk was still there in the year following when this little enclave was given the name of ‘Shakespeare Square’. Unfortunately, the next available directory is for 1784, in which year he had moved about a half mile westward to Hanover Street. Shakespeare Square disappeared with the Theatre Royal in the 1860’s to make way for new buildings, the centrepiece of which was the General Post Office, the grand facade of which still stands.[47]

Successful as he was as a merchant, he was perhaps inclined too much to trust his managers at the mine, as a result of which fell into a situation similar to the one that had befallen his father in 1750 (BJC, p. 225). Being cheated out of nearly half his expected profit, he eventually decided to ‘act as his own coal grieve’, i.e., manager.[48] Like his brother George and their mutual friend Dr James Hutton, he too had invested in the Forth and Clyde Canal, and now, rather than paying out, it was consuming money by way of additional cash calls (see §8.10). But he had also made a much wiser decision to invest in the Carron Iron Works[49] which paid out quite well on at least one occasion (Bertram, 2012, p.26) and thrived as a business until the late 20th C. Nevertheless, how did he get involved in such an enterprise? Interestingly, he was involved along with his brother-in-law John Adam, the architect, who had become a director of the company in 1763.[50] John and Robert Adam designed firebacks and balustrades for the ironworks to manufacture and sell,[51] some examples of which are now in the collections of the V&A Museum.[52]Their father, William Adam, who had been the Baron’s architect for Mavisbank, had become wealthy by developing diverse business interests including mining, salt panning and quarrying; it then fell to his eldest son John to carry these on. Shrewdly, John also added to them, specifically he invested in the ironworks, in which he saw the potential benefit of casting as a means of mass producing architectural structures and ironmongery. It was as they say nowadays, a ‘win-win situation’ for both him and the ironworks, and effectively one of the greatest steps forward in manufacturing by taking it into the era of mass production.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

In addition to the Pendreich mine, Carron Iron Works and the Forth and Clyde Canal, it is likely that in the 1770’s John Clerk, like his brother James, got involved in their brother George’s mining activities (see 8.12 and 8.13). Certainly, he visited Wanlockhead in 1775, for he did a pen and wash drawing there of the mines in operation (Plate 8.3) While he accompanied his friend Dr James Hutton on many tours, researching the mineral deposits and gathering geological evidence, George had done the same thing in 1764 (see §8.14). Occasionally, Hutton visited the mineral prospecting areas in the southwest of Scotland and had offered advice on what possibilities certain places might have to offer. It is therefore credible that John Clerk was fully conversant with the situation and, no doubt being assured by George of the certainty of an eventual profit, he would have either invested in the Craigtown Mining Company or at least lent him some of the money that he needed to get the mine going. But as we have seen, that story did not have a happy ending, for the mine consumed much more cash than it paid back leaving George and his co-investors on the brink of ruin. James forwent the debts George owed him and John may have been left in a similar position, for we find him in 1781, when the problems with the mine were emerging, trying to find a position as Comptroller of Customs at Leith, only to be rebutted by his former friend, Henry Dundas, then Lord Advocate and later Lord Melville:[53]

I perfectly recollect the conversation I had with you respecting the Comptrollership…. Lord North is under engagement… which will not leave it in my power to promote your wishes upon this occasion.

Dundas was a man of political import and major landowner in the neighbourhood of Lasswade, and John Clerk had purchased the parkland for his estate of Eldin from him some years before.[54] In the following year, having swallowed his pride, he tried again, this time for the position of Secretary to the Commissioners for the Annexed Estates,[55] of which George was already a Commissioner. Even so, he was once again unsuccessful, and as a result of Dundas’ apparent offhandedness he vowed he would not further demean himself by going to him again.[56] Nevertheless, he did obtain the position in the following year (Smith, 1975, p. 14) when he had instead the assistance of a Baron of the Exchequer, Sir John Dalrymple, who was also successful in getting appointed as a Commissioner (Smith, 1975, p. 395). Interestingly and somewhat ironically, although Henry Dundas was also appointed as a Commissioner, he did not oppose Clerk’s application for the Secretaryship. In September 1783, Clerk received a letter from Sir John advising him to:[57]

…be so good as not to mention to any one what passed between you and me about the annexed estates.

By that time, the position was likely to have been clear that the Secretaryship was Clerk’s. But Dalrymple could well have been warning him, in the light of Dundas’ appointment, of what was in store, the irony being that Dundas was on a mission to put a bill before Parliament to wind up the Annexed Estates and to reinstate them to the heirs of the former owners. Indeed, Dundas’ Act was given the royal assent in the following August and the Commission was disbanded at Martinmas (November) 1784. It could hardly have left poor John Clerk with any better opinion of Dundas than he already had. A man not to be crossed, Henry Dundas became one of the most prominent British politicians of his day, for which he was created Viscount Melville[58] and gained the soubriquet ‘King Henry IX’.

If John Clerk’s engagement with the Commissioners for the Annexed Estates had been bitter-sweet inasmuch as it was already being wound up, it was not the only bitter pill at that time. His appointment came just months after the death of his brother James, and when George succeeded James as Baronet, he was already ill and lasted just less than a year. Their widowed sister, Janet, also died on 24 January 1784, just five days before George. However, Sir James at least had left him a bond of provision for £2000, and his widowed sister left him everything in her will.[59] It seems to have been a case of bad timing rather than bad taste when John Clerk took out the lease of a new house on Hanover Street on 26January 1784 in the days between these two family deaths, but nevertheless the legacies he received would have helped his finances and meant that he need worry less about his short-lived appointment.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

Drawing seems to have long been a natural ability running in the Clerk family, and John Clerk of Eldin was no exception. We must suppose he developed his expertise with the pencil in his school years, as it is a frequent indoor pastime of youngsters when they have the opportunity of quiet play, but the first to be seen of a serious attempt is a view of St Andrews (Clerk of Eldin & Laing, 1855) that he executed in 1758. Clerk travelled far and wide throughout Britain in the holiday season taking in the sights and sketching them wherever he went. Over the years his travels encompassed such diverse places as the Scottish Highlands, Wales, Arran and Bute,[60] and as far west as the south coast of Cornwall in England, where he drew Smeaton’s new lighthouse on the Eddystone Rocks. With no cameras available for recording the highpoints of such trips, someone who had the facility of drawing scenery made an excellent companion. Many of his excursions were undertaken in the company of his friend James Hutton, with mineralogy and geology in mind, and Clerk’s pencil was just as adept, not only in recording formations of particular interest, but in creating sections of what lay underneath based on Hutton’s interpretation of the evidence they had seen on the surface. In earlier days, Hutton had accompanied George Clerk Maxwell on trips to the north of Scotland on his tours of duty as a Trustee for the Board of Manufactures and Commissioner for the Annexed Estates. On such occasions it had been George’s turn to contribute to Hutton’s geological records, but it is more likely that George would have made the sort of sketches appropriate to a scientific record. His younger brother, on the other hand, produced what were not only scientific records but also works of art. While his surviving drawings provide a clear insight into Hutton’s work,[61] they are also a testament to John Clerk’s own contribution as his assistant and draftsman.

In 1774, however, Clerk turned his artistic inclination towards etching,[62] the object of which is ostensibly to be able to reproduce an original drawing as many times as desired, but which also affords the possibility of creating certain unique effects that depend on the particular etching process employed. The reason he gives for taking up this fairly laborious pursuit is that some friends, Paul Sandby amongst them, had persuaded him to try it (Bertram, 2012a, p. 41). Although he did sell some of the prints he made, it does not seem that his main objective was commercial gain, rather he mainly wanted see what he could achieve. The technique suited him because his eyesight was more compatible with working close up rather than at arm’s length, which is the reason he gave for not attempting drawing or painting landscapes (Bertram, 2012a, p. 47). Another factor very much in its favour was that he would have had, by this time, a fairly large collection of drawings from which he could choose scenes as subjects to work on. Furthermore, he had always liked working with his hands, of which drawing was just one particular manifestation (Clerk and Laing, 1855).

Having struggled at first to master the technique, he at last began to succeed and before long he was experimenting with a variety of effects, eventually including aquatint[63] when he was just about at the end of his active period. Over a period of about seven years, he produced over 100 etchings,[64] a comprehensive account of which has been given by Bertram in his 2012 book The Etchings of John Clerk of Eldin, which we have frequently referred to above. From Kilchurn Castle and Castle Stalker in the northwest of Scotland, to Salisbury in the far south of England, Pembroke in southwest Wales, Newark in the East Midlands, Arran, Fife, Ayrshire, Dumfries, Durham, Glasgow, as well as closer to home, we can see therein fruits of his labours.

Like his brother George, John Clerk, was one of the original fellows of the Society of Scottish Antiquaries, through which he came into contact with David Steuart Erskine, the Earl of Buchan, an antiquarian who had been the prime mover in setting up the Society. Buchan suggested that a set of Clerk’s etchings should be presented to king George III, which he took upon himself, as a courtier who had access to the King, to do in May 1786. Protocol dictated that the presentation be done indirectly through the King’s private secretary, and so the etchings were accompanied by an explanatory letter for the King’s benefit when he got round to taking a look at them. Buchan generously added the following postscript to the letter:

Of these interesting etchings, some of which are tinted by Mr Robert Adam of Adelphi, you will find about fourscore; [65] … Mr Clerk is a most ingenious and excellent man, and the whole family is so respectable and amiable, that if his Majesty is pleased to order any notice of the communication, it shall give great pleasure to me if it shall be addressed to Mr. Clerk rather than to me. (Clerk and Laing, 1855)

As far as we know, after producing just one aquatint, Clerk’s passion for etching came to an end in 1782. He had found a new passion to consume his leisure hours, naval studies. By his own account, he started to think about this in 1770, even before he started etching. John Playfair,[66] who in 1805 gave us the biography of Dr James Hutton, worked on a similar biography of John Clerk but only got so far as a ‘fragment’ of it, which specifically concerned his remarkable acheivement in producing a revolutionary book on naval tactics (Playfair, 1823).[67]

As a boy, John Clerk had read about ships and the sea in such epic tales as Robinson Crusoe. He had played with model boats, some of his own making, on the ponds in the grounds of his father’s estate at Penicuik. When he was at school at Dalkeith, he had learned about boats from some boys who had a model ship and knew boats well, and when staying in Edinburgh he frequently had the opportunity to see the real things close up at the busy port of Leith, and to go on board some of them. He was never to be a seaman himself, but he was fascinated by ships and seafaring. His older brother Henry had been a first-lieutenant in the Royal Navy serving in the East Indies (BJC, p. 203). By way of his occasional letters and even rarer visits home, he would also have heard the sort of tales that would have whetted an interest in ships and seafaring. Following Henry, George’s sons John and James also gone to sea and so, despite his own lack of experience in naval matters, he would have had plenty of exposure to talk of such things within his family circle.

In adult life, John Clerk’s interest in the sea and naval affairs was stirred again by reports of actions at sea during periods of war, in particular the American War of Independence (1776-83). Reports of ignominious losses for the Royal Navy, for example, at the battle of Chesapeake Bay in September 1781, would have been splashed over the front pages of the newspapers of the day, and evidently Clerk studied these reports avidly and wondered why things had gone so badly wrong:

…the actions which were then happening at sea, served to convince Mr Clerk that there was something very erroneous in the methods hitherto pursued by the British admirals… (Playfair, 1823, p. 116)

Naval battles were usually set peices, with the ships on both sides formally lined up broadside to broadside, firing cannon volley after cannon volley in the hope that the opposing ships would be the first to collapse and crumble, and so it was that John Clerk began thinking that there had to be a better way of going about it. It so happened that he had a neighbour at Eldin, Captain James Edgar[68] who was a Commissioner of Customs alongside his elder brother George. Edgar had seen and taken part in many naval battles and so he could give Clerk first hand information on what took place in a battle and the typical sort of tactics that would be employed. This proved to be grist to John Clerk’s mill and so by 1781, having analysed a wide range of possible tactical situations, ‘from that of Admiral Matthews, off Toulon, in 1744, to that of Admiral Greaves off the Chesapeake in 1781’, and taking into account such factors as not only the direction of the wind and the direction of the enemy but also the direction that each side was travelling in, he began formulating new ideas on the subject in an essay entitled An Enquiry into Naval Tactics. Having illustrated it with his own explanatory figures and drawings, he had fifty copies printed for private circulation by the beginning of January 1782 (Clerk of Eldin, 1827).

The nub of John Clerk’s thinking was that in a conventional broadside to broadside attack, the available firepower was spread out far too thinly over the whole of the enemy’s line, whereas:

…the remedy consisted in concentrating the force of the attack, and in bringing it to bear with proportionally greater energy on a single point, or a small portion of the enemy’s line… At the time when this method of attack was proposed, it was regarded as a manoeuvre quite new, and as having never yet been acted on. (Playfair, 1823, p. 119)

The novelty of his method was indeed borne out by his own analysis of the major naval battles over the previous thirty seven years but, as fate would have it, there were to be counterclaims as to who actually originated it.

Amongst his researches, John Clerk had made an analysis of the Battle of Ushant, which took place between the British and French fleets in 1778. Both sides had about thirty ships, but the result was inconclusive and left the British with more than 1000 men killed or wounded, more than twice the number of casualties sustained by the French. The details of the battle had been widely reported as a result of the court-martial of Admiral Keppell furnishing Clerk with all the information he needed. About three years prior to his essay being printed, he had published his conclusions in a pamphlet which he circulated to ‘several naval officers, and to his friends both in Edinburgh and London’. He had followed this up in 1780 with a visit to London where he met with many naval men, including Mr Richard Atkinson,[69] who was a close friend and associate of Admiral Sir George Rodney and Sir Charles Douglas, who later served with Rodney as his Captain at the Battle of the Saints off Dominica in April 1782. By this time some copies of Clerk’s work had come into circulation. According toPlayfair (1823, p.125):

Sir Charles, before leaving Britain, had many conferences with Mr Clerk on the subject of naval tactics, and, before he sailed, was in complete possession of [Clerk’s] system.

The controversy arose when Rodney appeared to follow Clerk’s new system, which was called ‘breaking the line’. Instead of the usual broadside to broadside tactics, Rodney cut through the line of French warships and was able to concentrate the full force of his guns on the nearest enemy ships. Clerk tells of the reaction:

[My essay] was published by the 1st of January 1782. A few copies, only 50 in number, were printed, and handed about among friends: some copies I took the liberty to present to professional men. Very soon, however, I found that my system, so far as it then went, had excited a good deal of attention; and I was much gratified by the many flattering letters of approbation which I received, not only from men of letters, but from naval officers of distinguished merit, and of the highest rank. (Clerk of Eldin, 1827, pp. XLII-III)

While Rodney had sailed before the publication of the essay, it was asserted that a copy had been brought out to him by Douglas and, moreover, Clerk’s pamphlet could well have been known to both men for some time. Rodney was supposed to have had it communicated to him by Atkinson, while Clerk had allegedly met Douglas in London at the house of his brother-in-law, Robert Adam, (Douglas, 1832, p. 45) where in the presence of James and William Adam they had discussed Clerk’s tactics and presumably his pamphlet. While this may all be open to claim and counter claim, as certainly was the case for years afterwards, it is quite likely that neither of these very senior men took Clerk at all seriously. New ideas are not always welcome, and coming from a landlubber who got his theories by reading newspaper accounts and playing with cork boats, they would have been most unwelcome. One can well imagine John Clerk and his ideas simply having been humoured for politeness’ sake.

All the same, by April 1780, Rodney had attempted to depart from the orthodox battle formation at the Battle of Martinique. On this occasion he signalled his fleet to focus their attack on the French rear, but some of his captains were nonplussed by what they thought was an erroneous signal and carried on regardless. The opportunity had been lost, and the day ended with Rodney blaming his captains for disobeying, while they in turn blamed him for not giving them prior notice of his unusual battle plan. Almost exactly two years later at the Battle of Saints off Dominica, Rodney apparently had a repeat of his earlier inspiration. Followed by several of his ships, he broke through the enemy line about its middle and was able to pour devastating fire on the French ships thus caught out, including the French Admiral’s flagship which was severely damaged. But the reality was a little more prosaic, for the battle had started conventionally enough with both fleets broadside to broadside. In spite of this, when the French ships had passed down the line of their enemy, they had to manoeuvre so as to turn and go back along the line to give the British ‘some more of the same’. A few of the turning ships were caught out by an awkward change of wind, and a sufficient gap formed between them to let the watchful Rodney seize upon the opportunity to break through. The question is, did Rodney have Clerk’s ideas in mind when he did so, or did he simply seize the opportunity that lay before him?

The story gets even more complicated, for Major-General Sir Howard Douglas Bt. (1776‒ 1861) was later to maintain that Rodney was incapacitated by illness during the action, and that it was his father, Captain Charles Douglas, whose idea it was to break the line. Howard Douglas eventually wrote a book (1832) in which he systematically, and in great detail, set about refuting every other possibility. In particular, he declared in the strongest terms that neither his father nor Admiral Rodney had any knowledge of Clerk of Eldin’s Naval Tactics prior to Dominica. On the other hand, by John Clerk of Eldin’s own account written in 1804 (Clerk of Eldin, 1827, pp. XXIX‒XLV) the story is different, the meetings with Richard Atkinson and Charles Douglas did take place, and Rodney thereafter wrote some notes in a copy of Clerk’s book (these notes were eventually included by Clerk in the 1804 and subsequent editions). In addition, Clerk tells us that Rodney had privately given him credit for the idea of ‘breaking the line’ and had praised the value of his book in general. Even Lord Melville, who had been condescending towards John Clerk (see above), had declared before witnesses that Rodney had indeed acknowledged his debt of gratitude to John Clerk’s opus.[70] Certainly, Howard Douglas regarded Rodney as being vainglorious and ready to ignore inconvenient truths when it came to an opportunity to take the credit for a victory. Since Rodney had publicly claimed credit for himself, the only way he could have avoided embarrassment would have been to admit to the thing in private while playing it down in public.

It would be a fair reading of the situation that Rodney had heard about Clerk’s ideas, either through the good offices of Richard Atkinson or by hearing talk of the pamphlet, but had dismissed them with a sniff, as almost every dyed-in-the-wool naval officer would have done at the time. But whatever he thought of Clerk’s ideas, it is possible that once he actually saw the situation arising before him during the development of a battle, he did not hesitate to capitalise on it. The fact that it happened twice, and that the circumstances came about more by chance rather than by intention, seem to support this. However it came about, those who knew John Clerk could not believe that he would stoop to embroider claims about imparting his ideas to Rodney (albeit through Atkinson) and Douglas in London. Moreover, there were family witnesses to the meeting with Douglas. In spite of the considerable brouhaha, in due course John Clerk, sailor or no, was generally credited with changing the fortunes of the Royal Navy by coming up with the idea of ‘breaking the line’.

The debate, often heated, dragged on for nearly fifty years. Individually, naval officers would commend Clerk, but as a body the Navy would not yield up the discovery of the breaking of the line to a landsman; that would have simply been admitting they did not know their own craft. Playfair’s assessment was:

It might seem to derogate from the glory of our Naval Officers, to recognise a Landsman as the author of one of the most valuable discoveries that had been made in their own art… Jealousy, in the present instance, was a weakness that deserves no indulgence… it is a duty which I most willingly discharge, to say, that the Naval Officers with whom I have had the honour to converse on this subject, have all in the most unequivocal terms expressed their conviction of the importance and originality of Mr Clerk’s discovery… A National Monument that would have marked the era of this great improvement, and testified the gratitude of the Nation to the author, [John Clerk,] would have been …an acknowledgment from the Navy… would have been highly becoming… (Playfair, 1823, pp. 136‒7)

Even Sir Walter Scott, who was a friend of the Clerk family through John Clerk’s sons William and James, got involved in defending John Clerk as being the first to suggest ‘breaking the line’. He even inserted a footnote in praise of Clerk into his Life of Napoleon Buonaparte (Scott, 1827, p. 237f).[71] Howard Douglas, however, was intent on his father having been the originator of the successful manoeuvre at the Dominica, and during 1829‒32, so carried away was he by his cause that he published three books on it, (Douglas, 1829, ‘30 and ‘32). The first two of these publications were accompanied by a spate of letters[72] and they were also ‘reviewed’ in The Edinburgh Review (1830, pp. 1‒38), in what was effectively a refutation of Douglas’s claim that the facts spoke out for his father. The author’s name is not stated, but it has been suggested that it was Sir John Barrow, who had been a naval secretary during the time of Napoleonic Wars;[73] William Clerk was also active in defending his father’s claims about that time.[74] In Douglas’ last publication, which followed this review, he asserted that Sir Walter Scott had given in to the weight of evidence in support of Douglas’ father, and urged him to publish it (Valin, 2009, p. 72).

When all was said and done, John Clerk of Eldin was remembered and revered for ‘breaking the line’ for many years to come, for in one way or another it proved instrumental in changing the fortunes of war, in particular during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Had his ideas never come to light, the Battle of Saints in 1782 could have gone either way. If it had been a victory, the idea of ‘breaking the line’ would have been either Rodney’s or Douglas’ to claim; but if so, it would nothave been the result of a revolutionary rethink of naval tactics. In plain, battles are unpredictable and mistakes create advantages to be seized, and as is often said, the victor not only claims the glory but writes the history. Had either of these gentlemen been thinking long and hard about it beforehand, such an original idea would surely have been much discussed and would have become known by a sufficient number of people for Clerk’s work, when it appeared, to be widely dismissed as being unoriginal. The evidence appears to be to the contrary.

With Clerk’s book having been printed three months before the battle, and having been circulated to such important figures as Lords North, Shelburne and Sandwich; to Henry Dundas; and eventually, at Lord Montagu’s suggestion, even presented to the King,[75] it was plain for all to see that at the very least John Clerk had fairly well predicted how the Battle of Saints was actually won by Rodney and Douglas. This single fact on its own gave Clerk, the landsman, all the credibility he needed.

If Rodney and Douglas had been unaware of Clerk’s work, they must have been completely dumfounded to discover such a prediction had been made by anyone at all, let alone a landsman. The ensuing controversy achieved two things, first of all it simply amplified the publicity surrounding Clerk’s feat; everyone was talking about it and he was encouraged to publish more. But more importantly, the real naval brains of the day sat up and took note; whether or not they actually followed Clerk’s book to the letter, they did now think differently. Nelson was one such hero who was prepared to innovate. A resounding example of the new tactics being put use was the Battle of Trafalgar, which took place in October 1805; Nelson’s plan was to break the line of the combined French and Spanish fleets and to concentrate his forces on the weaker of the two parts. Nelson attacked from the west with his fastest ships running ahead to strike in the centre of the enemy fleet, which was lined up conventionally in a north to south arc. Despite his own death from sniper-fire, the result was a decisive victory, with no ships lost and two thirds of the enemy fleet captured.

By the time of Trafalgar, Clerk’s book had no doubt been assiduously studied by the admirals of every country possessing a navy and so Villeneuve, the French Admiral, must have had some inkling of what was likely to happen:

…[he] was painfully aware that the incomparably more expert British fleet would not be content to attack him in the old-fashioned way, coming down in a parallel line and engaging from van to rear. He knew that they would endeavour to concentrate on a part of his line. (Hannay, 1911)

Why, therefore, did he have no suitable counter-plan? The answer is that his fleet was a mixture of French and Spanish ships that he did not feel he could rely on to execute anything out of the ordinary. In short, they had not yet learned the lessons that the British Navy had by now taken to heart, and Villeneuve knew it.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

By 1788, John Clerk had moved his Edinburgh residence from Hanover Street to 70 Princes Street.[76] He was in his sixtieth year and a famous man, celebrated as the genius of ‘breaking the line’. He still travelled, he still liked to draw, and he was working on completing the remaining parts of his Enquiry on Naval Tactics, which was republished in 1790 and then again in 1797, this time with the addition of parts two, three and four. In 1804 it was published again under the title An Essay on Naval Tactics, Systematical and Historical, and it was this edition that first included Rodney’s notes to Part 1, as well as a preface giving John Clerk’s own version of the events and circumstances surrounding the communication of his idea to Rodney and Douglas. In addition to his continuing work on tactics, he had also time to think up a scheme for raising sunken ships, in particular HMS Royal George, which had sunk at Spithead in 1782.[77] Although parts of the Royal George were salvaged, it was never refloated.

From 1799, Clerk no longer listed himself in the Post Office directory, which suggests that by the age of seventy he wanted to lead a quieter life. Eventually he and Susannah moved to 16 Picardy Place to live with their eldest son John; it was 1805 and they had been married for over half a century. None of their children had married, and so their daughters moved with them. While we must presume William moved there too, their sailor son James was already dead, having died of yellow fever at Antigua in August 1796.[78] Susannah died in April 1808 and by 1811 John senior retired to live out his final days at Eldin, where he died on 10 May 1812. In later life he had become somewhat forgetful, for it is told by Kay (vol 2, No. CCCXX, 1877) that he put the printing of the 1797 edition of Enquiry on Naval Tactics in the hands of William Smellie but, despite having read the proofs and marked them up in his own hand, he dumfounded Smellie by refusing to pay his account on the grounds that he had never engaged him to do the work. In every account of John Clerk of Eldin, he is much admired for his two greatest achievements, his etchings and his ground-breaking book on naval tactics. But he was also successful in business and contributed much to Hutton’s work, for which his drawings were to become an integral part of Hutton’s legacy. He had enjoyed society and had been a member of the Oyster Club[79], the Select Society and its successor the Poker Club, and like his brother George he had been a founder fellow of the RSE. Lord Henry Cockburn’s assessed him thus:

…he was an interesting and delightful old man; full of the peculiarities that distinguished the whole family – talent, caprice, obstinacy, worth, kindness, and oddity; a striking-looking old gentleman, with grizzly hair, vigorous features, and Scotch speech, equally fond of a joke and an argument. (Cockburn, 1856, pp. 258-9)

He was laid to final rest beside his wife in the family lair at the Old Kirk in Lasswade.

▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪ . ▪

Over the years, John Clerk of Eldin and his wife Susannah had several children: Mary born 1754, Sarah 1756, John 1757, Susannah 1759, Elizabeth 1764, William 1770 and finally James in 1773. Of John and William, who both became lawyers, John was better known, for he was a familiar character in his day and there are many interesting anecdotes about him. William was rarely in the limelight, but the youngest James is so little known that it is seems to be forgotten that he ever existed. In 1784, John was entering his final year of training as an advocate while William would have been in his final year at the High School, and young James, at the tender age of 11 was being readied for a career at sea, following in the footsteps of his much older cousins John and James Clerk who were the subjects of the previous sections of this chapter, but both men were at the end of their careers when young James was just starting out on his. As to the daughters, Elizabeth was a favourite of the author Elizabeth Grant, who was a neighbour of the Eldin family and knew her as ‘Miss Bessy’ (Grant, 1988). Miss Bessy is consequently the only one of the daughters that anything more is known of.

Sadly, none of John and Susannah Clerk’s children had a family of their own to carry on the Eldin line. The next three sections, however, will give a more detailed account of the lives of John Clerk of Eldin sons.

10.4 John Clerk, Lord Eldin

On John Clerk of Eldin’s death his estate was inherited by the elder of his two surviving sons who was also named John after his grandfather the Baron. At the age of fifty-five he became the new John Clerk of Eldin, but he is now always distinguished from his father by referring to him by his judicial title, Lord Eldin, which he did not assume until some twelve years later. By the time he succeeded to Eldin in 1812, he had earned himself a fearsome reputation in the courts and was generally regarded as the foremost advocate of his day. But originally he was not destined to become a lawyer, for it had come to his father’s attention that great fortunes were to be made in India. His nephew James Clerk, his brother George Clerk Maxwell’s second son (see §9.3), had joined the HEICS merchant fleet and from him and others he must have heard that the prospects there were enormous. There was great demand for young men to go to India as writers. The role was somewhat of a variation on the typical Scottish ‘writer’, for these were clerks trained rather more in accountancy than in the law; bookkeeping was an essential function for a company which required to keep vast quantities of goods and money flowing smoothly and to the right destinations. For the young writers the prospects seemed good: adventure in an exotic land, an office job with the prospect of climbing rapidly up the ranks, and ample opportunity to deal for themselves on the side. John Clerk senior had been a successful merchant, and it no doubt appealed to him as being a good prospect for his son. John junior was not to be a soldier or a sailor, for he was lame in one leg.[80] In 1782, James Clerk HEICS was writing to John Clerk senior in an attempt to persuade him to participate in the funding of an HEICS trading voyage with himself as captain.[81] He would sail back from Madras or Calcutta with the cargo, whereupon it would be sold at a huge profit to himself and the individual investors. At the same time, John Clerk senior’s nephew, William Adam MP, wrote to him concerning his attempts to get John Clerk junior a position as an HEICS writer, no doubt in the face of stiff competition.[82] These two events occurred closely together, probably in the late spring or early summer of 1782, because the letters concerned both refer to the reception received by John Clerk’s book on naval tactics. Adam tells him that Lord North had read it while James Clerk mentions that Admiral Barrington and Lord Howe had received it well. John Clerk must therefore have been seriously thinking about India as being the place where money was to be made, and indeed he may have had it in mind for some time, for John junior was by then training as an accountant, presumably through apprenticeship as a clerk.

But as we know, by 1782 Clerk senior was having difficulties with Henry Dundas, who was perhaps miffed by Clerk’s sudden rise to fame in matters naval, a sphere of interest in which he probably felt that he needed to be preeminent. Later in that year, preparations were being made for John junior’s departure for India[83] but for some reason or other, it was called off. As to the likely reason, we can only speculate, but there are two which readily emerge. The first is suggested by Paton:

…the expectations of his friends having been disappointed by the occurrence of certain political changes, his attention was turned to the legal profession. Kay & Paton, 1877, Part 2, p. 439

In late 1783, Charles Fox had introduced a Bill in Parliament that attempted to reform theEast India Company, it was defeated, but William Pitt the Younger passed such a Bill under his administration of the following year. The timing would seem too late to have prompted an abrupt change of career for young John Clerk, but of course the Bill would have been introduced to deal with a situation that had already been demanding attention. The previous legislation, whereby the East India Company had borrowed a huge sum of money from the government ,would have brought the Company’s monopoly to an end in any case by 1783. It therefore seems likely that by late 1782 hopes of an extension to that monopoly would have been fading, and indeed Pitt’s Act brought about a complete reformation the Company and its modus operandi. Paton’s suggestion is therefore credible.

The second plausible reason was that, as the Clerk’s gleaned more information about John junior’s prospects and the likely conditions he would meet in India, the truth would have emerged about the horrific mortality rate amongst the young writers. It is said that only one in ten returned to Britain to enjoy their wealth; of the rest, Calcutta, for example, is full of their graves. In addition, even at home in Scotland health was ever an uncertain matter; John may have by chance taken an illness which may have resulted in his doctor’s advising against the Indian climate; many such diseases and infections were ever on the go, and something as commonplace as a broken limb could end in permanent disability. Walter Scott, for example, had been struck by infantile paralysis as a child, and the Baron had nearly lost his life following a compound fracture of the leg. We simply do not know how John came to be lame, in indeed if it was at this critical time, but it is a possibility that cannot be dismissed.

Disappointed in his prospects of making his fortune in India, John Clerk had to look for another career. Paton, writing in 1838, says:

After completing his apprenticeship as a Writer to the Signet, and having practised for a year or two as an accountant, he qualified himself for the bar, and was admitted a member of the Faculty of Advocates in 1785. (Kay & Paton, 1877, Part 2, p. 438)

There is no mention of any of the Clerk family ever being admitted as a Writer to the Signet (1890), which in any case may have been the wrong sort of training for a career as an advocate. Given that Clerk did train as a ‘writer’ , Paton probably took it in the usual Scottish context; nevertheless it seems to have been the case that Clerk had already done sufficient legal training to become accepted as lawyer.

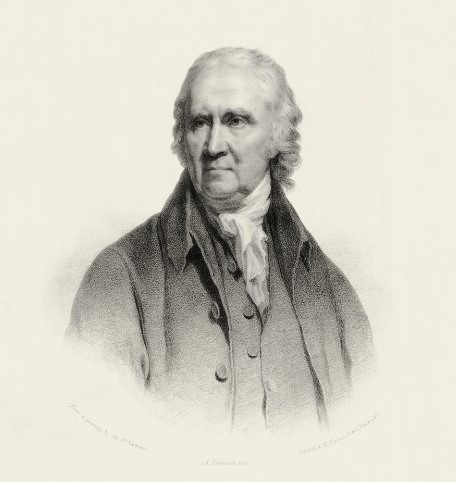

Mezzotint, published 1815.

© National Portrait Gallery, London. Reference Collection NPG D36131

This is confirmed by the fact that he obtained without further ado a ticket of admission to the Judicial Society, which was sent to him by Robert Dundas, its secretary.[84] He had already been apprenticed as a trainee advocate since the start of 1783, and within the space of three years was admitted as an advocate on 6 Dec. 1785 (Grant, 1944). During the while he seems to have had sufficient energy to continue practising as an accountant in Parliament Square.[85] John was another of the Clerk family who demonstrated a penchant for drawing. When, in 1787 he accompanied his father and Dr James Hutton on their geological excursion to Arran, it was mainly he who undertook the drawings on Hutton’s behalf (Playfair, 1803, p. 70). Modelling was another pastime that he not only excelled at but also exploited in some boyish pranks:

… having a great genius for art, [he] used to amuse himself with manufacturing mutilated heads, which, after being buried for a convenient time in the ground, were accidentally discovered in some fortunate hour, and received by the laird with great honour as valuable accessions to his museum. The most remarkable of these antique heads was so highly appreciated by another distinguished connoisseur, the late Earl of Buchan,[86] that he carried it off from Mr. Clerk’s museum, and presented it to the Scottish Society of Antiquaries — in whose collection, no doubt, it may still be admired. (Lockhart, 1837, vol 1, p. 94)

Lockhart (1820, p. 193) further says of him:

…he is himself a capital artist, and had be given himself entirely to the art he loves so well, would have been… the greatest master Scotland ever has produced.

An exaggeration, perhaps, but it serves to demonstrate the popular opinion of Clerk’s artistic abilities at the time. Lockhart expands on this in a sketch in which Peter, the supposed writer of the letter, tells of visiting a saleroom where he bought: